Identifying and Managing Dyer's Woad (Isatis tinctoria) in Pastures, Rangelands, and Non-Crop Settings

full bloom. Flowering usually occurs by

late spring.

Quick Facts

- Dyer’s woad outcompetes perennial forbs and grasses.

- Seeds are viable as green pods (fruits) appear.

- It’s adapted to many environments.

Introduction

Dyer's woad (Isatis tinctoria) was introduced into Utah during the mid-19th century as a source of indigo dye. The plant escaped cultivation and has spread across rangelands, foothills, and other sites throughout the Intermountain West (Figure 1).

Identification

white midvein and alternating pattern

of dyer's woad leaves.

Dyer’s woad leaves are lance-shaped with a white midvein on the upper surface of the blade. The leaves alternate up the stalks of mature plants (Figure 2).

Flower stalks form a flat top with many small yellow flowers. Petals and sepals are arranged in X patterns (Figure 3).

Mature fruits are pods containing a single seed. Young pods are lime green but turn dark purplish-brown as they mature. Dyer's woad has a thick, deep-growing taproot. Mature plants at flower may have purple stems (Figure 4).

Lifecycle and Distribution

Dyer’s woad is a winter annual, biennial, or a short-lived perennial. Plants spread by seed, which become viable relatively soon after flowering (Young & Evans, 1971).

dashed lines marking the X pattern

of petals.

Seeds germinate with the onset of fall, cooling temperatures, and where soil moisture is adequate. Seedlings often form a rosette the first year, then flower and set seed the following year (Figure 5).

Dyer's woad is abundant on Utah hillsides and valleys. The plant is well adapted to disturbed areas, rangeland, dry woodlands, fence lines, and other areas. Dyer's woad is a nuisance because it replaces native vegetation, resulting in livestock and wildlife avoidance or overgrazing of the remaining desirable plants, with the exception being grazing by small ruminants while plants remain immature.

Fortunately, other than the sheer number of acres infested, the weed is rather benign compared to some of the other widespread noxious weeds. In Utah, dyer's woad is a Class 2 noxious weed; namely, high priority for control (Lowry et al., 2012).

in bloom

Management

Prevention is always the preferred method to manage noxious weeds. Periodically, scout areas where new infestations are likely to occur, for example, fence lines, right-of-ways, cultivated land, and ditch banks. When choosing fill material, ensure that the source of the material is clean and free of weeds. Transport weed-free hay and feed horses and livestock weed-free hay prior to transporting them off of your property. Carefully clean equipment, tools, clothing, and footwear upon exiting infested areas.

Additionally, good cultural practices when farming or landscaping will help with management. Planting competitive crops or maintaining healthy plant cover in hay and pastures will limit dyer’s woad establishment and impacts. In new developments and residential areas, landscape early with plants that are well adapted to the area. Weed barriers and mulches are also useful.

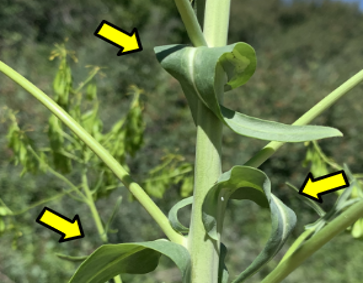

Mechanical removal is accomplished by pulling, hoeing, cultivation, or mowing. Pulling the plant up or ground cultivation is much more effective for smaller areas than hoeing or mowing. For larger plants or in large infestations, cutting the taproot to at least one shovel spade deep may be more efficient. Be mindful of maturing fruits as the flowers die (Figure 6). If fruits are present, bag the plants to prevent seeds from spreading.

Mowing is not particularly effective, but it can help if done early enough in the year. The plant will continue to make flower heads on much shorter stems after mowing. Follow-up cuttings may be needed.

surrounded by smaller seedlings

developing into rosettes.

Biocontrol is the process of introducing a natural predator or pathogen to control a pest. No known weed-feeding insects specific to dyer's woad have been identified at this time. However, Puccina thlaspeos (Figure 7), a fungus, demonstrates minor promise as a biocontrol agent (Lovic et al., 1988). This rust fungus may reduce plant vigor and seed production but won’t control dyer’s woad alone.

| Table 1. Summary of Non-Herbicide Options | |

|---|---|

| Control Method | Notes |

| Prevention |

|

| Cultural and mechanical (pasture) |

|

| Cultural and mechanical (rangeland) |

|

| Cultural and mechanical (non-crop) |

|

| Biocontrol |

|

At this stage of maturity, fruits may

contain viable seed.

Chemical Control

When used appropriately, herbicides can be an effective method to kill or prevent dyer’s woad (see Table 2).

Always read and follow the label when applying chemical herbicides. Pay special attention to safety requirements, restrictions of use, directions for use, and disposal requirements.

The location of application and the uses specified on the herbicide label will determine which herbicides are appropriate.

Be aware of surroundings, e.g., open water, slope, vegetation nearby, temperature, and wind when applying chemical herbicides.

Preemergence herbicides prevent seedlings from emerging. These herbicides are usually nonselective to seedlings and prevent most annual and perennial seeds from establishing. When used appropriately, these chemicals can be used to stop new woad plants from sprouting among desirable perennials.

Postemergence selective herbicides will kill certain types of plants, e.g., broadleaf weeds or grasses. Selective herbicides work well when dyer’s woad is growing in grass pastures and on rangeland. They also can be used in many non-crop settings.

infection. Note the rust-colored

spores.

Postemergence non-selective herbicides kill most or all actively growing plants, regardless of plant classification. Non-selective herbicides are useful in areas where vegetation is discouraged or for seedbed preparation.

Pasture

Good grazing practices are essential to maintaining a healthy pasture. Likewise, herbicides are effective tools for maintaining a healthy pasture. Some products labelled for selective control of broadleaf weeds can provide effective dyer’s woad control in permanent grass pastures, but they are not suitable for grass-legume mixed pastures as many herbicides labeled for pasture can injure or kill the legumes. In these situations, using preemergence herbicides, specifically labelled postemergence herbicides, spot treatments, or omitting chemical control are the only options available.

biodiversity as seen in this hillside

plant community.

Rangeland

Management of weeds on rangelands is important for maintaining the resource (Figure 8). Before applying herbicides, caution should be taken to be aware of your environment, e.g., slopes, aquatic areas, and sensitive plant species. Research at Utah State University (USU) has shown that specific herbicides are effective at controlling different life stages of dyer’s woad. In research plots, 2,4-D was effective against seedlings the year it was applied and weak on rosettes while Escort was effective against seedlings and rosettes. However, neither effectively controlled seedlings germinating the following spring. A new herbicide labelled for use in range (indaziflam) showed excellent suppression of dyer’s woad seedlings the spring after treatment.

Non-Crop

Examples of non-crop areas include but are not limited to the following sites: gravel areas, loading ramps, storage yards, vacant lots, railroad and rail yards, managed roadsides, fence rows, utilities, and parks. Ensure that the site being treated is approved on the label.

For complete vegetation control involving dyer's woad, herbicides labeled for preemergence and postemergence use in non-crop settings can be cost effective for large acreages, such as roadsides and fences.

Dyer's woad next to irrigation ditches and streams must be treated with care using only certain herbicides that are labeled for aquatic use.

| Table 2. Summary of Herbicides | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mode of action | Active ingredient | Trade name | Comments |

| Pasture | |||

| (Many products in Table 2 are labeled for pasture and rangeland, but restrictions are site-specific. Refer to the label.) | |||

|

Group 2 |

imazapic | Plateau | Provides good control for seedlings, rosettes, and bolting plants. Some residual control the following year. Applications > 4 oz/acre may temporarily suppress grass growth. |

| Group 2 ALS Inhibitors |

metsulfuron | Escort, MSM 60, etc. | Provides excellent control for seedlings, rosettes, and bolting plants. No residual control the following year. These products may temporarily suppress grass growth. |

| Group 2 ALS Inhibitors |

chlorsulfuron | Telar | Typically applied postemergence with some residual the next year. May temporarily suppress grass growth. |

| Group 4 Growth Regulators* |

2,4-D | Several names | Good control for seedlings and young rosettes. No residual control the following year. Pay special attention to the label to prevent drift. Avoid spraying 2,4-D when temperatures > 80°F. |

| Rangeland | |||

| (All products listed under Pasture can be used in rangeland. Refer to the label for specific instructions.) | |||

| Group 29 Cellulose Biosynthesis inhibitor |

indaziflam | Rejuvra | Newly registered herbicide (applied preemergence) can prevent seedling establishment and is very active on invasive annual grasses. Also prevents establishment of desirable seed; only use in areas where sufficient perennial plant cover currently exists. |

| Non-Crop | |||

| (Many products in Table 2 are labeled for sites other than pasture and rangeland. Restrictions are site-specific; refer to the label.) | |||

| Group 9 Aromatic amino acid inhibitors | glyphosate | Many names | Non-selective herbicide, which kill desirable plants--especially grasses. Good control of emerged seedlings and rosettes. |

| Group 29 Cellulose Biosynthesis inhibitor | indaziflam | Esplanade | Newly registered herbicide (applied preemergence) can prevent seedling establishment and is very active on invasive annual grasses. Also prevents establishment of desirable seed; only use in areas where sufficient perennial plant cover currently exists. |

*Except for 2,4-D, most other growth regulator herbicides (i.e., triclopyr, aminopyralid, picloram) provide minimal control of dyer’s woad.

Picture Credits

Utah State University Extension and authors provided all photos.

References

- Lowry, B. J., Ransom, C., Whitesides, R., & Olsen, H. (2017). Noxious weed field guide for Utah. All Current Publications. Paper 1352. Utah State University Extension. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/extension_curall /1352

- Lovic, B. R., Dewey, S. A., Evans, J. O., & Thomson, S. A. (1988). Puccinia thlaspeos —A possible biocontrol agent for dyers woad. Proceedings of the Western Society of Weed Science, 41, 55–57.

- Young, J. A., Evans, R. A. (1971). Germination of dyers woad. Weed Science, 19, 76–78.

Published June 2021

Utah State University Extension

Peer-reviewed fact sheet

Authors

Cody Zesiger, Utah State University Extension assistant professor; Jacob Hadfield, Utah State University Extension assistant professor; Corey Ransom, Utah State University associate professor and Extension weed specialist

Related Research