Opioids and Other Common Substances: What You Need to Know

Abstract

This fact sheet focuses on opioids, a highly addictive class of substance with a high risk of unintentional overdose death. We review how opioid overdoses can be temporarily reversed with naloxone (Dhalla, et al., 2009; Straus, et al., 2013) and some important resources.

Opioids and the Brain

Opioids are a class of substances that include prescription pain medications (e.g., oxycodone, hydrocodone, and codeine) as well as the illicit drug heroin (National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA], 2018). Heroin and prescription pain medications are addictive, have the same chemical structure, and perform similar neurological actions in the human body (NIDA, 2018). Opioids are a Central Nervous System (CNS) depressant that slow the signaling in the CNS and provide a reduced sensation of pain (Stoeber, et al., 2018). Opioids work by attaching to the opioid receptors (“ports” that send and receive signals) in the brain, which are responsible for sensing pain and preventing pain signals throughout the body (Huxtable, et al., 2011; Stoeber, et al., 2018; Lintzeris & Nielsen, 2010). Opioids are one of the most commonly used medicines for acute pain management due to their effectiveness and ability to attach to the receptors so effectively (Huxtable, et al., 2011; Stoeber, et al., 2018).

Opioid Overdose

As mentioned above, the use of opioids, especially in combination with other CNS depressants (e.g., alcohol, benzodiazepines), causes slowing or dulling of the CNS. As the body’s critical functions slow, they can reach a dangerous level of inactivity or stop all together, resulting in an overdose (i.e., a toxic amount of a substance that overwhelms the body and can result in death; Steynor & Macduff, 2015; Stoeber, et al., 2018). Knowing the signs and symptoms of an opioid overdose could save a life. If you or someone you love is using opioids (i.e., prescription pain medication or heroin), it is important to be aware of the signs and symptoms of an opioid overdose and know how to administer naloxone quickly during an emergency (Green, et al., 2008).

| Common Substances Used with Opioids That Increase Risk of Overdose |

|

Benzodiazepines and Opioids |

| Alcohol and Opioids Alcohol is one of the riskiest substances that can be taken with opioids, since alcohol and opioids both depress the CNS resulting in slowed signaling and breathing (Gudin, et al., 2015). Research has found that alcohol is used with opioids more frequently than any other substance (Hickman, et al., 2008; Larance, et al., 2016). The most dangerous consequence of consuming alcohol with opioids is alcohol’s ability to cause “slow-acting” opioids to rapidly release their chemicals and increase their chemical actions in the body unintentionally (Gudin, et al., 2015). |

What to do in an Overdose Emergency

In an overdose situation, always call for emergency medical services (EMS) help first, then administer naloxone (Narcan ©) to provide a temporary overdose reversal and prevent overdose death until EMS arrives (Rando, et al., 2015). Remember the acronym CCAPSS (Call 9-1-1, Check Circulation, Airway, Pupils, Slurred Speech, and trouble Staying Awake) if you find yourself in a possible overdose situation (Schiller, 2019):

CALL 9-1-1 Immediately

Check circulation: "Do they have a pulse?"

Airway: "Are they able to breathe on their own? Are their lips blue or pale?"

Pupils: "Do they have pinpoint, or very small pupils?"

Slurred Speech: "Are they able to talk without severe slurring or mumbling?"

Staying Awake: “Do they seem to have trouble staying awake? Are they unconscious or unresponsive?”

If the person has difficulties in any of the above areas, they may be experiencing an opioid overdose. If you have naloxone on hand it would be appropriate to administer it.

Naloxone

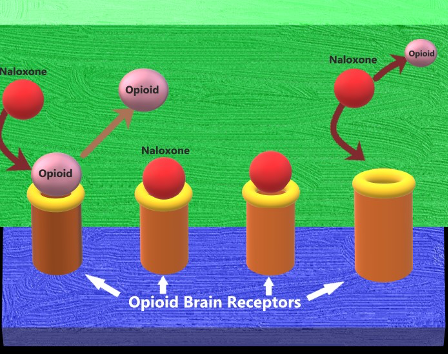

When opioids enter the brain, they act like a “key” and insert into specific opioid receptors, similar to a “lock” (Straus, et al., 2013). Naloxone has the potential to “knock” opioids off the brain’s opioid receptors. However, this only works for a short duration (approximately 30-90 minutes) before the opioids will re-attach to the brain’s receptors. In some cases where there are high levels of opioids present, a person may overdose multiple times or an overdose may require multiple doses of naloxone to reverse the overdose effects (Straus, et al., 2013; Lynn & Galinkin, 2017). Figure 1 shows how naloxone works on the brain’s opioid receptors to reverse an overdose.

Figure 1. Naloxone removes opioids from the brain receptor and attaches itself, reversing the effects of opioid overdose temporarily (e.g., Straus, et al., 2013).

What Else Should I Know?

In 2016, Utah passed the “Opiate Overdose Response Act” which allows pharmacists to dispense naloxone by the use of a “Standing Order” to anyone, without needing a prescription (Balough, et al. 2019; *some restrictions apply). Additionally, the “Good Samaritan Law” allows bystanders to report an overdose and provides some protections against prosecution in order to save a life (Balough, et al. 2019; *some restrictions apply). Please see Table 1 for a brief list of where to find more information.

Table 1. Opioid, Naloxone, and Emergency Resources and Websites

| General Utah Resources | Naloxone Websites | Emergency Numbers | Therapy Locator Websites |

|---|---|---|---|

| 211utah.org | Naloxone.org | 911 (EMS & Police) | Utahaddictioncenters.com |

| Opidemic.org | Utahnaloxone.org "Free Naloxone rescue kits available" |

1-800-273-8255 (Suicide Hotline) |

Intermountainhealthcare.org |

| Health.utah.gov. | Naloxoneforall.org | 1-800-222-1222 (Poison Control) |

Findtreatment.samhsa.gove |

| Utahsuicideprevention.org |

Note. All of the resources provided are for educational purposes and USU does not specifically endorse their services. Cognitive behavioral and other cognitive resources are intended to provide information, not to treat chronic pain or other mental health concerns. USU does not control the websites or books referenced above.

Always consult your medical provider when considering seeking treatment or management of a medical condition and/or medications.

Learn More:

In its programs and activities, Utah State University does not discriminate based on race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, genetic information, sexual orientation or gender identity/expression, disability, status as a protected veteran, or any other status protected by University policy or local, state, or federal law. The following individuals have been designated to handle inquiries regarding non-discrimination policies: Executive Director of the Office of Equity, Alison Adams-Perlac, alison.adams-perlac@usu.edu, Title IX Coordinator, Hilary Renshaw, hilary.renshaw@usu.edu, Old Main Rm. 161, 435-797-1266. For further information on notice of non-discrimination: U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, 303-844-5695, OCR.Denver@ed.gov. Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Kenneth L. White, Vice President for Extension and Agriculture, Utah State University.

References

- Balough, M., Nwankpa, S., & Unni, E. (2019). Readiness of Pharmacists Based in Utah About Pain Management and Opioid Dispensing. Pharmacy, 7(1), 11. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy7010011

- Dhalla, I. A., Mamdani, M. M., Sivilotti, M. L., Kopp, A., Qureshi, O., & Juurlink, D. N. (2009). Prescribing of opioid analgesics and related mortality before and after the introduction of long-acting oxycodone. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 181(12), 891–896. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090784

- Gomes, T., Mamdani, M. M., Dhalla, I. A., Paterson, J. M., & Juurlink, D. N. (2011). Opioid Dose and Drug-Related Mortality in Patients With Nonmalignant Pain. Archives of Internal Medicine, 171(7). doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.117

- Green, T. C., Heimer, R., & Grau, L. E. (2008). Distinguishing signs of opioid overdose and indication for naloxone: an evaluation of six overdose training and naloxone distribution programs in the United States. Addiction, 103(6), 979–989. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02182.x

- Gudin, J. A., Mogali, S. D., Jones, J. D., & Comer, S. undefined. (n.d.). Risks, Management, and Monitoring of Combination Opioid, Benzodiazepines, and/or Alcohol Use. Clinical Focus: ADHD, Psychiatric Disorders, and Pain Management, 125(4), 115–130. doi: doi.org/10.3810/pgm.2013.07.2684

- Hickman, M., Lingford-Hughes, A., Bailey, C., Macleod, J., Nutt, D., & Henderson, G. (2008). Does alcohol increase the risk of overdose death: the need for a translational approach. Addiction, 103(7), 1060–1062. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02134.x

- Huxtable, C. A., Roberts, L. J., Somogyi, A. A., & Macintyre, P. E. (2011). Acute Pain Management in Opioid-Tolerant Patients: A Growing Challenge. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, 39(5), 804–823. doi: 10.1177/0310057x1103900505

- Jones, C. M., Mack, K. A., & Paulozzi, L. J. (2013). Pharmaceutical Overdose Deaths, United States, 2010. Jama, 309(7), 657. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.272

- Jones, C. M., & Mcaninch, J. K. (2015). Emergency Department Visits and Overdose Deaths From Combined Use of Opioids and Benzodiazepines. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49(4), 493–501. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.040

- Kameg, B. (2019). Shifting the Paradigm for Opioid Use Disorder: Changing the Language. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 15(10), 757–759. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2019.08.020

- Larance, B., Campbell, G., Peacock, A., Nielsen, S., Bruno, R., Hall, W., … Degenhardt, L. (2016). Pain, alcohol use disorders and risky patterns of drinking among people with chronic non-cancer pain receiving long-term opioid therapy. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 162, 79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.02.048

- Lintzeris, N., & Nielsen, S. (2010). Benzodiazepines, Methadone and Buprenorphine: Interactions and Clinical Management. American Journal on Addictions, 19(1), 59–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2009.00007.x

- Lynn, R. R., & Galinkin, J. (2017). Naloxone dosage for opioid reversal: current evidence and clinical implications. Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety, 9(1), 63–88. doi: 10.1177/2042098617744161

- Marel, C., Sunderland, M., Mills, K. L., Slade, T., Teesson, M., & Chapman, C. (2019). Conditional probabilities of substance use disorders and associated risk factors: Progression from first use to use disorder on alcohol, cannabis, stimulants, sedatives and opioids. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 194, 136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.10.010

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2018). Opioids. Retrieved April 9, 2020, from https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids

- Rando, J., Broering, D., Olson, J. E., Marco, C., & Evans, S. B. (2015). Intranasal naloxone administration by police first responders is associated with decreased opioid overdose deaths. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 33(9), 1201–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.05.022

- Schiller, E. Y. (2019, December 27). Opioid Overdose. Retrieved April 9, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470415/

- Stoeber, M., Jullie, D., Laeremans, T., Steyaert, J., Schiller, P. W., Manglik, A., & Zastrow, M. V. (2018). A genetically encoded biosensor reveals location bias of opioid drug action. Neuron, 98(5), 963–976. doi: 10.1101/254490

- Straus, M., Ghitza, U., & Tai, B. (2013). Preventing deaths from rising opioid overdose in the US – the promise of naloxone antidote in community-based naloxone take-home programs. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, 65. doi: 10.2147/sar.s47463

Authors

Justin R. Sacco, Health & Wellness Intern, B.S, NREMT; Ashley Yaugher, Ph.D.; Tim Keady, M.S., CHES; Kandice Atismé, MHA, MPH, CPH

Related Research