Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS):

What You Need to Know

7% of females report opioid use during pregnancy, and 21% of those report misuse of opioids.19

National overdose deaths continue to rise, with 2021 marking the first time U.S. overdose deaths topped 100,000 in a 12-month timeframe. Substance use, such as alcohol, cocaine, opioids, and marijuana, during pregnancy is also increasing.1 As the U.S. struggles with harmful substance use, a growing number of infants are born with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), a harmful outcome of fetal exposure to substances.2

In the U.S., one newborn is diagnosed with NAS every 24 minutes.20

This fact sheet will talk about why and what to do, with recommendations for safe treatment and support during pregnancy.

What Is Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS)?

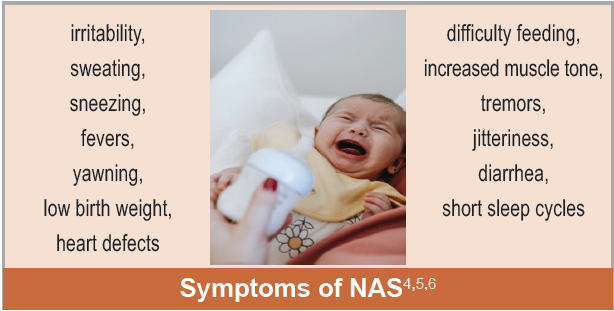

NAS is the cluster of withdrawal symptoms infants experience after birth caused by exposure to substances in utero.3 All opioids can cause NAS, including illegal drugs like heroin, prescription drugs like oxycodone or fentanyl, and drugs used for treating opioid use disorder.4,5

Females who have a substance use disorder (SUD) can have social, psychological, and medical histories that may present risk factors affecting the health of the pregnancy and the infant.7

Associated risk factors of SUD and NAS include:4,5,6,7,8

- Parents, family members, and friends whoalso have a SUD.

- Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), suchas sexual, physical, and emotional abuse.

- Mental health conditions, such as depressionand exposure to trauma.

- Use of tobacco or other substances, such asalcohol or sedatives.

- Exposure to infectious diseases.

- Poverty.

Is NAS Something I Should Worry About?

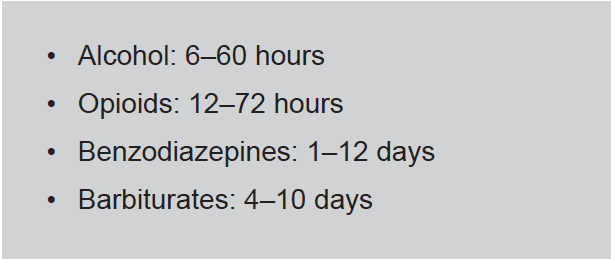

When an infant is born to a person using substances, the infant is at risk of withdrawal. Withdrawal symptoms of NAS can develop within 24 hours after birth or take longer to appear, with the recommendation that infants be monitored for up to 72 hours.5,6 For infants experiencing significant NAS symptoms, despite supportive treatment, medications are used.6 Once the infant is displaying fewer symptoms of NAS, healthcare professionals will slowly wean the infant off the medications. An infant no longer needs to stay in the hospital once they are no longer receiving NAS treatment medications for at least 24 hours, are medically stable, and are eating and growing properly.5,6

There were 4x as many females with opioid use disorder in 2014 than just 15 years before.21

Since NAS co-occurs with other developmental stressors, it can be difficult to isolate the impact. ACEs, like NAS, can have long-term negative impact on brain development, immune systems, and stress-response systems during childhood.9 Children born with NAS are more likely to experience maltreatment, mental health problems, and behavioral problems.3

What Medications Treat Dependency in Pregnancy?

Figure 1. Timeline for Maternal Withdrawal Symptoms

Note: Estimations were provided by the New York State Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services.

Although medication-assisted treatment (MAT) contributes to fetal exposure, it is the recommended treatment for a pregnant individual.7,10 MAT reduces the risk of severe neonatal abstinence syndrome, preterm birth, overdose, HIV/AIDS, and death.10

Detoxing as a form of treatment is associated with high rates of relapse and overdose and is consequently not recommended for pregnant individuals.7,10 Careful medication management should be encouraged. The symptoms of NAS can be more severe if an infant is additionally exposed to nicotine, benzodiazepines, or antidepressants (although, the benefits of antidepressants in pregnancy outweigh the risks).5,6,7 Overall, medication for addiction treatment is currently the best treatment option for most pregnant people and their infants.

Figure 2. Self-Evaluation of Possible Substance Use Disorder (SUD)

Note. Information was adapted.11,12

Medication-Assisted Treatment

Methadone: a synthetic, long-acting opioid that prevents withdrawal symptoms, decreases cravings, and does not have a euphoric effect if used appropriately.

Buprenorphine: an opioid-similar drug that is used by itself or in combination with naloxone (an opioid antagonist) to prevent the euphoric high effect of the opioid.

Naltrexone: an opioid antagonist that removes the euphoric high of opioid use. Naltrexone is rarely used in pregnancy.

Note that Kratom, an opioid-like herbal extract used for pain relief, is used recreationally. It should not be used during pregnancy.10

How Do Moms Get Needed Help?

Of children in foster care for SUD involvement, 73% are reunified with family members.22

Infants born where harsh penalties for substance-using pregnant females exist had higher rates of NAS than those born in states without such punitive policies. Many individuals with SUD reported they did not want to alert anyone that they used substances for fear of losing the custody of their child. The fear of losing custody can keep females from seeking treatment or from being compliant in their treatment.

Females who use substances during the prenatal and postpartum periods should seek health care providers who are respectful, empathic, and willing to have a collaborative relationship. This type of care will go further than stern reprimands to encourage engagement with clinical services and reduce feelings of stigma.3

Postpartum females who have an opioid use disorder (OUD) are more likely to overdose in the postpartum period compared to the prenatal period. This could be attributed to the lack of resources provided for females with OUD. Professional peer support, where clients work with someone who has overcome similar behavioral health challenges, can be a less stigmatizing environment for females who are pregnant.17

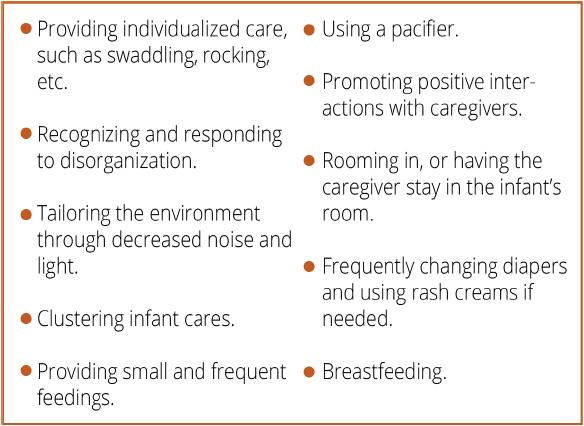

Figure 3. Examples of Supportive Treatments

Sources 5,6

How Do Babies Get Needed Help?

Supportive measures can prevent the use of medication or decrease the amount of medication needed to treat NAS in infants.5

Breastfeeding is recommended for many infants with NAS. Breastfeeding should be encouraged for mothers who are currently abstaining from substances or receiving MAT as prescribed.5,7,10 If an infant previously diagnosed with NAS is displaying any developmental problems, it is important to talk to the child’s pediatrician, who may refer the child to an early intervention service.5

What Can Communities Do?

Community members can minimize diversion of medications by safely disposing of prescription opioids. All unused or expired medications must be disposed of properly. See the suggestions for proper methods for safe medication disposal in the picture below.

Source18

Everyone can also work to give support to those who use substances or might be struggling due to NAS. Avoiding stigma helps individuals get the help they need.

Additional Resources

Use these websites and resources to find more information on treatment for substance use during pregnancy. Remember to consult a doctor or health care professional before starting any treatment program.

| Organization | Website |

|---|---|

| Al-Anon/Alateen | |

| Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health | safehealthcareforeverywoman.org |

| Communities That Care | communitiesthatcare.net |

| CRAFT Family Support | myusara.com/support/craft/ |

| Early Intervention Program | https://health.utah.gov/cshcn/programs/babywatch.html |

| Naloxone | naloxone.utah.gov/ |

| National Harm Reduction Coalition | harmreduction.org/ |

| National Substance Use Treatment Locator | findtreatment.gov/ |

| National Suicide Prevention Lifeline Dial 988 | suicidepreventionlifeline.org/ |

| Parents Empowered | parentsempowered.org/ |

| SafeUT | safeut.med.utah.edu/ |

| SMART Recovery | myusara.com/smart-recovery-at-usara/ |

| Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) | samhsa.gov 1-800-662-HELP (4357) |

| The Opidemic | opidemic.org/ |

| United Way (2-1-1) | 211utah.org/ |

| Use Only as Directed | useonlyasdirected.org/ |

| USU Health Extension: Advocacy, Research Teaching (HEART) Initiative | extension.usu.edu/heart/ |

| Utah Coalitions for Opioid Overdose Prevention | ucoop.utah.gov/ |

| Utah Department of Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health | dsamh.utah.gov/ |

| Utah Poison Control Center (1-800-222-1222) | poisoncontrol.utah.edu/ |

| Utah Prevention Coalition Association | utahprevention.org/ |

| Utah Support Advocates for Recovery Awareness | myusara.com/ |

References

1 Sebastiani, G., Borrás-Novell, C., Casanova, M. A., Pascual Tutusaus, M., Ferrero Martínez, S., Gómez Roig, M. D., & García-Algar, O. (2018). The effects of alcohol and drugs of abuse on maternal nutritional profile during pregnancy. Nutrients, 10(8), 1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10081008

2 Viteri, O. A., Soto, E. E., Bahado-Singh, R. O., Christensen, C. W., Chauhan, S. P., & Sibai, B. M. (2015). Fetal anomalies and long-term effects associated with substance abuse in pregnancy: A literature review. American Journal of Perinatology, 32(5), 405–416. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1393932

3 McQueen, K., & Murphy-Oikonen, J. (2016). Neonatal abstinence syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine, 375(25), 2468–2479. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1600879

4 Watson, C., Mallory, A., & Crossland, A. (2019). The spiritual and ethical implications of medication-assisted recovery in pregnancy: Preserving the dignity and worth of mother and baby. Social Work & Christianity, 46(3).

5 Patrick, S. W., Barfield, W. D., Poindexter, B. B., Cummings, J., Hand, I., Adams-Chapman, I., Aucott, S. W., Puopolo, K. M., Goldsmith, J. P., Kaufman, D., Martin, C., Mowitz, M., Gonzalez, L., Camenga, D. R., Quigley, J., Ryan, S.A., & Walker-Harding, L. (2020). Neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome. Pediatrics, 146(5). doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-029074

6 Jansson, L. M. (2021, September 2). Neonatal abstinence syndrome. UpToDate. Retrieved April 24, 2022, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/neonatal-abstinence-syndrome#H1

7 Saia, K. A., Schiff, D., Wachman, E. M., Mehta, P., Vilkins, A., Sia, M., Price, J., Samura, T., DeAngelis, J., Jackson, C. V., Emmer, S. F., Shaw, D., & Bagley, S. (2016). Caring for pregnant women with opioid use disorder in the USA: Expanding and improving treatment. Current Obstetrics and Gynecology Reports, 5(3), 257–263.

8 National Institute of Mental Health (2021, March). Substance use and co-occurring mental disorders. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved April 25, 2022, from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/substance-use-and-mental-health#:~:text=A%20substance%20use%20disorder%20(SUD,most%20severe%20form%20of%20SUDs

9 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022, April 6). Fast facts: Preventing adverse childhood experiences. Violence Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/fastfact.html

10 Seligman, N. S., Rosenthal, E., & Berghella, V. (2021, November 10). Overview of management of opioid use disorder during pregnancy. UpToDate. Retrieved April 25, 2022, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-management-of-opioid-use-disorder-during-pregnancy?topicRef=5016&source=see_link

11 Brown, R. L., & Rounds, L. A. (1995). Conjoint screening questionnaires for alcohol and other drug abuse: Criterion validity in a primary care practice. Wisconsin Medical Journal, 94(3), 135–140.

12 Hinkin, C. H., Castellon, S. A., Dickson-Fuhrman, E., Daum, G., Jaffe, J. & Jarvik, L. (2001), Screening for drug and alcohol abuse among older adults using a modified version of the CAGE. The American Journal on Addictions, 10, 319–326. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-0391.2001.tb00521.x

13 Faherty, L. J., Stein, B. D., & Terplan, M. (2020). Consensus guidelines and state policies: The gap between principle and practice at the intersection of substance use and pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MFM, 2(3), 100137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100137

14 Howard, H. (2015). Experiences of opioid-dependent women in their prenatal and postpartum care: Implications for social workers in health care. Social Work in Health Care, 55(1), 61–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2015.1078427

15 Stone R. (2015). Pregnant women and substance use: Fear, stigma, and barriers to care. Health & Justice, 3, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40352-015-0015-5

Note. References within Stone’s article include:

Murphy, S., & Rosenbaum, M. (1999). Pregnant women on drugs: Combating stereotypes and stigma. Rutgers University Press.

Poland, M. L., Dombrowski, M. P., Ager, J. W., & Sokol, R. J. (1993). Punishing pregnant drug users: enhancing the flight from care. Drug and alcohol dependence, 31(3), 199–203.

Roberts, S. C., & Nuru-Jeter, A. (2010). Women’s perspectives on screening for alcohol and drug use in prenatal care. Women’s Health Issues, 20(3), 193–200.

Roberts, S. C., & Pies, C. (2011). Complex calculations: how drug use during pregnancy becomes a barrier to prenatal care. Maternal and child health journal, 15, 333–341.

16 Proulx, D. & Fantasia, H. C. (2021), The lived experience of postpartum women attending outpatient substance treatment for opioid or heroin use. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 66, 211–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.13165

17 Hand, D. J., Short, V. L., & Abatemarco, D. J. (2017). Treatments for opioid use disorder among pregnant and reproductive-aged women. Fertility and Sterility, 108(2), 222–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.06.011

18 Use Only as Directed. (2022). Throw out. Know Your Script. https://useonlyasdirected.org/throw-out/

19 Ko, J. Y., D’Angelo, D. V., Haight, S. C., Morrow, B., Cox, S., Salvesen von Essen, B., Strahan, A. E., Harrison, L., Tevendale, H. D., Warner, L., Kroelinger, C. D., & Barfield, W. D. (2020). Vital signs: Prescription opioid pain reliever use during pregnancy — 34 U.S. jurisdictions, 2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), 69(28), 897–903. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6928a1

20 Winkelman, T. N. A., Villapiano, N., Kozhimannil, K. B., Davis, M. M., & Patrick, S. W. (2018). Incidence and costs of neonatal abstinence syndrome among infants with Medicaid: 2004–2014. Pediatrics, 141(4), e20173520. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3520

21 Haight, S. C., Ko, J. Y., Tong, V. T., Bohm, M. K., & Callaghan, W. M. (2018). Opioid use disorder documented at delivery hospitalization - United States, 1999–2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), 67(31), 845–849. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30091969/

22 Utah Department of Human Services: Child and Family Services. (2021). DCFS annual report: Fiscal year 2021. https://dcfs.utah.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/DCFS-2021-Annual-Report.pdf

Published May 2023

Utah State University Extension

Peer-reviewed fact sheet

Authors

Maren Wright Voss, Amelia Van Komen, Emily Hamilton, Aarica Cleveland, Jaclyn Miller