Buying a Home Freeze-Dryer: What to Know Before You Go

Freeze-dried foods are extremely popular among backpackers and culinary masters, and now freeze-dryers are available for home use. The advertising is enthralling, the possibilities seem endless: Space-age food at the push of a button! Never waste a leftover again! Gleaming, inviting, New Age—the siren call to Americans who love their gadgets.

But is a home freeze-dryer the appliance for you? Here is some information designed to cut through the advertising hype and provide a voice of reason on the pros and cons of home freeze-dryer ownership.

The Science Behind Freeze Drying

What is freeze drying?

According to the FDA: “Lyophilization or freeze drying is a process in which water is removed from a product after it is frozen and placed under a vacuum, allowing the ice to change directly from solid to vapor without passing through a liquid phase. The process consists of three separate, unique, and interdependent processes; freezing, primary drying (sublimation) and secondary drying (desorption)” (FDA Inspection Guides, 7/93, updated 2014). Freeze drying takes advantage of the scientific principle of “sublimation,” the direct transition of a solid to a gas, by removing ice (the solid) from frozen food as water vapor (a gas). Using sublimation, the food retains much of its original texture, flavor, and nutrition when rehydrated.

Freeze drying is broken down into two simple processes: freezing and vacuum drying. Foods are first frozen to well below 0°F. The colder the freeze the more efficient the next step will be. Once frozen, foods are subjected to vacuum drying. The air and water vapor (gas) are removed from the food processing chamber using a vacuum pump. This includes removing the water vapor that was once inside of the foods. When these two steps are properly completed, the food is dry enough to allow for safe storage at room temperature.

Is freeze drying food safe?

Yes, If...

- The two sub-processes, freezing and vacuum drying are done correctly:

- The freezing process must be quick and the vacuum process should leave only residual moisture.

- For example, chilling foods safely is defined as reaching 41°F (refrigeration temperature) in 1-4 hours or less. Pre-refrigerated or pre-frozen foods can be placed in the freeze-dryer to minimize this concern.

- Drying foods safely is defined as reaching “a safe residual moisture level.” To determine this at home, most Cooperative Extension resources suggest that foods should be dried to a “crisp” or “breakable” texture, although foods with high levels of sugars, such as fruits, may be flexible, but not sticky, when correctly dried (Andress, Harrison, Reynolds, and Williams, 2014)

- Proper safe food handling techniques were employed in the preparation of the food prior to freeze-drying. Freeze-drying does not kill bacteria.

What happens to microorganisms in the freeze-drying process?

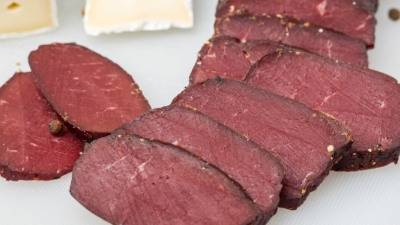

Nothing. The microorganisms stay viable, but dormant, even under the extreme conditions of freeze drying. In fact, scientists use a laboratory version of freeze drying to preserve microorganisms for future studies because the microorganisms can be rehydrated alive for decades (see Kupletskaya & Netrusov, 2011). Therefore, when home freeze drying raw foods the microorganisms on those raw foods will remain viable, then activate upon rehydration. Food items that are traditionally cooked before eating must also be cooked before eating as a freeze-dried food. Examples are raw meats, raw seafood, raw eggs, and foods containing these raw ingredients.

Can freeze dried foods be safely vacuum packaged?

Yes. As long as the food is dried to a low residual moisture, vacuum packaging is safe. Remember, vacuum packaging is not a food safety process itself. In fact, removing oxygen from a package may make it more of a concern for the botulism bacteria to grow and produce toxin if there is a moist environment. Fortunately, without moisture (water) the botulism bacteria (and all bacteria, yeast, and molds) cannot grow. Therefore, it is safe to place properly dried or freeze-dried foods in vacuum packaging or in containers that also have oxygen absorber packets placed inside.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Advantages of Freeze-drying

- Easy preparation. Food is prepared for freeze-drying the same way food is prepared for regular freezing. After rinsing and removing blemishes, blanch most vegetables; pretreat fruits if necessary to prevent browning; meats can be freeze-dried cooked or raw; casseroles are typically assembled from already cooked foods. Place the product on the trays and push the button to start the machine.

- Freeze-drying can preserve foods other preservation methods cannot, such as most dairy or egg products.

- Freeze-drying can replace pressure canning of low acid foods.

- Storage. When finished, freeze-dried products are shelf-stable, lightweight, and food safe for longer other food preservation methods. Conservative food safety estimates of commercial food “canned” in metal-Mylar-type pouches is 8 to 10 years (Jahner & Nummer, 2008). This does not address the food quality after that time, only the food safety. However, no real data exists on the shelf-life of home freeze-dried products, because the company that invented and manufactured the first home freeze-dryer began sales in 2013.

- Nutrition. Nutrition labels of commercially freeze-dried broccoli, pineapple and cooked chicken chunks compare favorably to nutrient data of raw or commercially frozen products (see the USDA Food Composition Database).

- Taste. Freeze-dried products rehydrate more fully than dehydrated products, so the taste and texture are closer to fresh with a freeze-dried product than with a dehydrated product.

- Cost. Home freeze-dried foods are substantially cheaper than commercially freeze-dried foods. Even including supplies and electricity costs, the commercial companies often have a mark-up of up to 85% more than a home-produced product (Jessen, 2018).

Disadvantages of Freeze-drying

- Cost. The machine itself (starting around$2,000 and ranging to over $10,000 for small commercial ones) is not the only cost. The ongoing cost of supplies must be considered.

- The price for 60 mylar 1-gallon bags with 60 300 cc oxidizer packets is $24 on Amazon (October 2018). The oxidizer packets are a one-time use, although the mylar bags could possibly be cut down and reused.

- Cost of vacuum pump oil starts at $20 a gallon, although that oil can be filtered and reused. An oil-less pump is also an option but will be an upfront cost of

$1,600 (Harvest Right, November 2018) when buying the machine. - Reports on the cost of electricity have varied. One consumer on the East Coast said her electricity bill went up $20 to$30 a month during her heavy usage time (Merrill, 2018, personal correspondence). Consumers in the Intermountain West figured between $2 to $5 worth of electricity per batch

(Jessen, 2018).

- Options: consumer choices for this appliance are currently limited. There are few companies making “home” freeze dryers, laboratory freeze dryers are built for scientific sampling so may not work as well for food, and the small commercial “pilot study” freeze dryers tend to be larger than those marketed for home use. Additionally, laboratory and commercial freeze dryers typically have more sophisticated software programs that significantly increase the price. However, these are all options for consumers who want to thoroughly search the market.

- Size of machine. This is not a small appliance, as shown by the table below using specifications from a popular “home” freeze dryer manufacturer:

| Cost | Batch Size | Outside Dimensions |

|---|---|---|

| Large: $2,995 | 12 to 16 pounds (peach bushel about 48 pounds) | 22.5" x 25.5" x 32.5" weighs 253 pounds |

| Medium: $2,395 | 7 to 10 pounds | 20" x 25" x 30" Weighs 212 pounds |

| Small: $1,995 | 4 to 7 pounds | 16.5" x 18.5" x 25" weighs 139 pounds |

See if a home freeze dryer is worth the cost in this article Is Buying a Home Freeze Dryer Worth It?

- Installation of unit. This appliance cannot sit on the floor: both because it must be elevated for the ice melt tubing to drain into a container below it, and to be able to access the vacuum pump and the on/off switches for the unit.

- Temperature. Freeze dryers, like most machines, work best in ambient temperatures of 45o to 80o F. The pump throws out heat, so it is important to put the machine in an area where there is plenty of ventilation (Harvest Right, n.d.).

- Noise. When the vacuum pump turns on, the noise level is 62 to 67 decibels—a vacuum cleaner is 70 dB. (EpicenterBryan, 2018; and iac acoustics, 2018).

- Time. Typical batch time is between 20 to 40 hours (Harvest Right, 2018). Very dense foods and foods high in sugar take longer: fresh pineapple takes between 48 to 52 hours.

- Batch quantities. The mid-size machine handles between 7 to 10 pounds of food. A bushel of peaches is 48 pounds. Figuring a 24- hour process time plus a 3-hour defrost time to make the machine ready for another batch, it would take over a week to freeze-dry one bushel of peaches. That is assuming the bushel of peaches can wait to be processed for a week.

Compare the differences between freeze dried food and dehydrated food in this article Freeze Dried vs Dehydrated Foods: Complete Comparison

Conclusions

Consider the following questions when thinking about purchasing a freeze-dryer:

- What is the end goal of your product?Backpacking? Family dinner? The Apocalypse?

- What tastes best? Some foods may taste better to you using traditional preservation methods, others may taste better to you preserved by freeze-drying. Know what your personal preferences are to determine the efficacy of owning a home freeze-dryer. Trying out some commercially freeze-dried food might help in this quest.

- Does freeze-drying fit in your budget and does the appliance fit in your home?

It is fun to experiment with innovative preservation methods, but carefully consider the consumer purchasing points above: Know before you go.

References

- Andress, E. L., Harrison, J.A., Reynolds, S., Williams, P. (2014). Drying. In, So easy to preserve, sixth edition (Bulletin 989). Athens, Georgia: Cooperative Extension/The University of Georgia/Athens, College of Family and Consumer Sciences, College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences.

- EpicenterBryan. (2017, December 14). Vacuum pump for Harvest Right freeze dryers. Retrieved from https://theepicenter.com/blog/oilless-maintenance-free-harvest-right-freeze-dryer-pump/

- Harvest Right. (2018). Harvest Right Owner’s Manual. Retrieved from http://www.acrossintl.com/Files/HR_FreezeDryer_Manual.pdf

- iac acoustics, (2018). Comparative noise examples. Retrieved from http://www.industrialnoisecontrol.com/comparat ive-noise-examples.html

- Jahner, B,. & Nummer, B.A. (2008). Food storage: Canned goods. Utah State University Extension Fact Sheet. Retrieved from https://extension.usu.edu/foodstorage/howdoi/canned

- Jessen, C. (2018). Freeze drying foods. Unpublished presentation at Annual Conference of Utah Extension Association of Family and Consumer Sciences, Kaysville, Utah.

- Kupletskaya, M.B., & Netrusov, A.I. (2011). Viability of lyophilized microorganisms after 50-year storage. Microbiology, Vol. 80, No. 6, 850-853. Pleiades Publishing.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. (2014). Lyophilization of Parenteral (7/93) (FDA Guide to Inspections of Lyophilization of Parenterals). Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/ICECI/Inspections/Inspecti onGuides/ucm074909.htm#_top

Authors

Cathy Merrill, Brian Nummer, Christine Jessen, Paige Wray, Callahan Ward

Related Research