Skills to Support Mental Health in Uncertain Times

Part 3: Being Engaged

Introduction

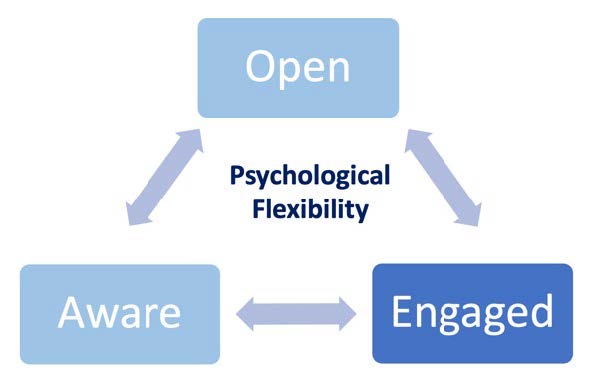

Psychological flexibility is comprised of several processes (Ciarrochi et al., 2010). This fact sheet is the third in a series of three fact sheets. It addresses the skill of being engaged; the other two address being open and being aware.

A great way to increase your life satisfaction during difficult times is by actively engaging in what matters most to you (Flowers et al., 2023; Wąsowicz et al., 2021). By engaging in actions that matter to you, you can live the life you value rather than allowing uncomfortable thoughts or feelings to keep you stuck (Hayes, 2020). This can protect your quality of life when you experience distress (Levin et al., 2020).

Skill Overview: Engaging Fully

Being engaged involves aligning your actions with your core values or what matters most to you. It includes actively participating in life and taking steps toward what matters most even when you’re facing challenging circumstances (Hayes, 2020). This can be done through setting meaningful goals and committing to follow through with these goals.

Application: Engaging Fully

Examine and Clarify Your Values

Reflect on what truly matters to you in life. Consider your relationships, career, personal growth, health, community, and hobbies. In each of these areas, these values represent the qualities you want to prioritize in your actions.

- Research shows that writing down your values is more helpful than just thinking about them (Hayes, 2020).

- On either your phone or a piece of paper, write down one or two things you value in each of the following areas: relationships, career, health, and hobbies.

- Remember, values change and evolve. This activity is helpful to repeat regularly.

Set Meaningful Goals

One way to help you turn your values into action is by setting meaningful goals. Values-based goals can help provide a sense of purpose and direction. It’s easy to set goals that are unachievable by thinking too big or too generally. Consider using “SMART,” an acronym to help you set an achievable goal. Make goals that are:

- Specific.

- Measurable.

- Attainable.

- Relevant.

- Time-bound.

This useful acronym can help you set goals that may reduce stress and help you live in line with your values (Weintraub et al., 2021); however, it’s not the best fit for all goals! It’s okay to focus on just two to three of these elements as you set your goals.

Example

Diana and Dave both value being patient and gentle with their children, but when they’re experiencing stress or other uncomfortable thoughts and feelings, they will often react to these feelings by yelling at their children. Both decide to set a goal to help them live better according to their values.

- Diana decides that she will never yell at her children again.

- Dave thinks about when he yells the most—it’s usually when he’s tired or hungry. He makes a goal to go to bed 30 minutes earlier each night and include protein in each of his meals to help him stay satisfied longer. He plans to write in his journal each night and record whether he yelled at his children and how he could have prevented getting to the point of yelling. After a week, he will assess his progress and consider whether he needs to make additional changes to his daily schedule to help him avoid yelling.

Which of the five parts of SMART goals did Diana meet? Which ones did Dave meet?

Practice

Think about your values. Choose one value you want to focus on. Consider ways you can live aligned with that value. Set a goal using the SMART acronym (or the parts of it that make sense to you) to help you act according to your values.

Take Committed Action

- Once you’ve set a clear and attainable goal, decide on the specific steps you will take to achieve your goal.

- Communicate this specific goal to someone you deeply care about. Research indicates that when we share a commitment, we are more likely to follow through with it (Hayes, 2020).

Develop Resilience

- Engaging fully does not mean avoiding difficulties or setbacks. Instead, it is all about embracing challenges as opportunities for growth.

- Practicing self-compassion, accepting and learning from failures, and seeking support when needed helps build resiliency. This resiliency will help you remain actively engaged during hard times.

Practice

If you fall short of your goal, for whatever reason, acknowledge that you didn’t meet your goal. Consider whether you need to revise your goal before committing to it again.

- Being open, aware, and engaged are all interconnected!

- Revisit the activities in the related two fact sheets in the “Skills to Support Mental Health in Uncertain Times” series to help you remain flexible as you work toward and adapt your goals.

Take a Step Back and Remove the Pressure

While values-based goals will be the most meaningful, sometimes they can create pressure (Kroska et al., 2020). It can be helpful to practice following through with a goal just to show yourself that you can (Hayes, 2020). Set a goal that doesn’t have any specific reason behind it. It can be something like the following:

- "This month, I’ll spend 15 minutes every morning reading a book I enjoy.”

- "I’ll crochet for a few minutes before bed every night until I run out of yarn.”

- "I’m going to make my coffee every day this week instead of going to Starbucks.”

Remember, the only “why” behind these goals is because you choose to set that goal and follow through!

For more information about psychological flexibility and to access additional skill building exercises, see the website Steven C. Hayes, Ph.D. To focus specifically on becoming more engaged, scroll to the ACT Tools section on this webpage and look at the “Values” and “Commited Action” exercises.

References

-

Ciarrochi, J., Bilich, L., & Godsell, C. (2010). Psychological flexibility as a mechanism of change in acceptance and commitment therapy. In R. Baer (Ed.), Assessing mindfulness and acceptance: Illuminating the processes of change (pp. 51–76). New Harbinger Publications.

-

Flowers, J., Eddy, A., McCullough, N., Christopher, M., & Kennedy, C. H. (2023). Acceptance and commitment therapy processes differentially predit aspects of mental health. Psychological Reports. doi: 10.1177/00332941231169673.

-

Hayes, S. C. (2020). A liberated mind: How to pivot toward what matters. Penguin.

-

Kroska, E. B., Roche, A. I., Adamowicz, J. L., & Stegall, M. S. (2020). Psychological flexibility in the context of COVID-19 adversity: Associations with distress. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 18, 28–33.

-

Levin, M. E., Krafft, J., Hicks, E. T., Pierce, B., & Twohig, M. P. (2020). A randomized dismantling trial of the open and engaged components of acceptance and commitment therapy in an online intervention for distressed college students. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 126, 103557.

-

Wąsowicz, G., Mizak, S., Krawiec, J., & Białaszek, W. (2021). Mental health, well-being, and psychological flexibility in the stressful times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 647975. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647975

-

Weintraub, J., Cassell, D., & DePatie, T. P. (2021). Nudging flow through ‘SMART’ goal setting to decrease stress, increase engagement, and increase performance at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 94(2), 230–258.

-

Wolf, K., & Schmitz, J. (2023). Scoping review: Longitudinal effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on child and adolescent mental health. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 1–56.

Published December 2023

Utah State University Extension

Peer-Reviewed Fact Sheet

Authors

Heather Kelley, Rachel Byers, Ty Aller, and Tim Keady

Related Research