Skills to Support Mental Health in Uncertain Times

Part 1: Being Open

Introduction

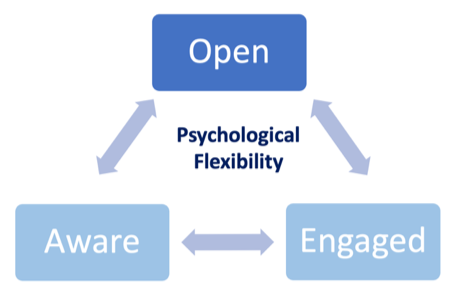

Psychological flexibility is comprised of several different skills (Ciarrochi et al., 2010). This fact sheet is the first in a series of three fact sheets. It addresses the skill of being open. The other two address awareness and being engaged.

Even now, several years since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, many individuals and families are still dealing with the impacts of the pandemic and its closures (De & Sun, 2023; Kohls et al., 2023; Wolf & Schmitz, 2023). The pandemic’s long-lasting impacts, along with economic instability and the wars in Ukraine and Israel, have created or amplified feelings of uncertainty for many individuals. This uncertainty can negatively impact individuals’ mental health (Daly & Robinson, 2021).

Developing skills that support psychological flexibility, or the ability to respond to difficult thoughts and feelings in a flexible and values-aligned way, can help individuals from various backgrounds protect and improve their quality of life when they experience mental health concerns such as depression or anxiety (Byrne & O’Mahony, 2020; Wersebe et al., 2018) or when upsetting events occur (Wąsowicz et al., 2021).

Skill Overview: Being Open

- Openness consists of two skills: first, the ability to accept the presence of difficult thoughts and feelings without judgment, and second, the ability to let these thoughts and feelings come and go, rather than getting stuck in them.

- When we are open, we accept uncomfortable thoughts or sensations such as stress and sadness. This allows us to shift our focus to how we react to these thoughts and feelings. When we focus on our actions, we can choose to let our values, or what matters most to us, guide what we do instead of letting our thoughts or feelings drive us. For example, if someone values being dependable, they can focus on acting in dependable ways, even when experiencing challenges.

- Being open creates space for difficult and meaningful experiences, which can improve mental health and well-being (Hayes, 2020).

Application and Practice: Being Open

Being open is a skill. Like all skills, it takes practice to develop. The following exercises can help.

Acceptance

One way to practice being open is to accept the uncomfortable thoughts and feelings you experience. This can be hard, especially when you start applying acceptance. To make this easier, it’s helpful first to practice accepting small things in the world around you. Let’s practice:

- Look around you and choose an item to focus on, whether it’s part of your clothing, a decoration, or something else.

- Stare at the item you’ve chosen and say “yes” to it five times. Each time you say yes, allow that yes to mean that you accept that item for what it is, whether it’s an ugly yellow chair, a cozy sweater, or a glass of ice water covered in condensation. In other words, if you choose the ugly yellow chair, you can look and think, “Yes, this is an ugly yellow chair. It belongs in this room, and it’s comfortable to sit on.”

- Now, choose a different item. Focus on it, and this time, say “no” to it five times. Each time you say no, consider what is wrong with this item. For example, if you choose the cozy sweater, you might think, “No, this sweater is stained and old. It needs to be washed and probably replaced.”

- Go back to the first item. Say “yes” to it five times again, accepting it as it is.

- Now, consider how you feel toward these two items. Are you better able to accept the item you said yes to?

- Continue practicing saying “yes” and accepting random items just the way they are for the rest of the day.

- After practicing this acceptance skill, try applying it to your thoughts and feelings. For example, you may feel a mixture of excitement and nerves for a family party. Say “yes” to these feelings, accepting them for what they are without trying to change them.

Letting Thoughts Come and Go

In addition to accepting thoughts for what they are, recognizing that thoughts come and go can help you avoid getting stuck in any particular thought.

Example

Tom’s diner closed for several months due to a kitchen fire, and he almost lost his family-owned business. He is still working to pay off debts incurred during this time. The thought, “What if there’s another fire or other disaster?” regularly bothers him, especially when he’s working on the diner’s finances. Instead of ignoring or following that thought down a rabbit hole, Tom first labels it and thinks, “I’m having this scary thought again.” Tom knows that this thought comes and goes often. As he recognizes and labels that thought, he finds it helpful to imagine it as a balloon that is floating by. He doesn’t get caught up in the thought and continues working on the diner’s balance sheets.

Practice

What is an uncomfortable thought that often visits your mind? The next time it visits, acknowledge the thought and label it, as described earlier. Then, take a moment to close your eyes. Imagine that thought as a balloon or a cloud floating across the sky. Allow that thought to exist and to float away, recognizing that uncomfortable thoughts will continually come and go.

It may feel awkward at first to label your thoughts and feelings, and it may be hard just to let them be. That’s okay—the more you practice being open, the easier and more automatic it will become.

For more information about psychological flexibility and to access additional skill-building exercises, see the website Steven C. Hayes, Ph.D. To focus specifically on becoming more open, scroll to the ACT Tools section on this web page and look at the "Defusion" and "Acceptance” exercises. Dr. Russ Harris, author of ACT Made Simple, also provides a wealth of free information and activities that can contribute to increasing psychological flexibility on his ACTMindfully website.

References

-

Byrne, G., & O’Mahony, T. (2020). Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for adults with intellectual disabilities and/or autism spectrum conditions (ASC): A systematic review. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 18, 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.10.001

-

Ciarrochi, J., Bilich, L., & Godsell, C. (2010). Psychological flexibility as a mechanism of change in acceptance and commitment therapy. In R. Baer (Ed.), Assessing mindfulness and acceptance: Illuminating the processes of change (pp. 51–76). New Harbinger Publications, Inc.

-

Daly, M., & Robinson, E. (2021). Psychological distress and adaptation to the COVID-19 crisis in the United States. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 136, 603–609.

-

De, P. K., & Sun, R. (2023). Impacts of COVID-19 on mental health in the U.S.: Evidence from a national survey. Journal of Mental Health, 1–8.

-

Hayes, S. C. (2020). A liberated mind: How to pivot toward what matters. Penguin.

-

Kohls, E., Guenthner, L., Baldofski, S., Brock, T., Schuhr, J., & Rummel-Kluge, C. (2023). Two years COVID-19 pandemic: Development of university students' mental health 2020–2022. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1122256.

-

Wersebe, H., Lieb, R., Meyer, A. H., Hofer, P., & Gloster, A. T. (2018). The link between stress, well-being, and psychological flexibility during an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy self-help intervention. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 18(1), 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2017.09.002

-

Wąsowicz, G., Mizak, S., Krawiec, J., & Białaszek, W. (2021). Mental health, well-being, and psychological flexibility in the stressful times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 647975. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647975

-

Wolf, K., & Schmitz, J. (2023). Scoping review: Longitudinal effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on child and adolescent mental health. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 1–56.

Published January 2024

Utah State University Extension

Peer-Reviewed Fact Sheet

Authors

Rachel Byers, Heather Kelley, Ty Aller, and Tim Keady

Related Research