Skills to Support Mental Health in Uncertain Times

Part 2: Cultivating Awareness

Introduction

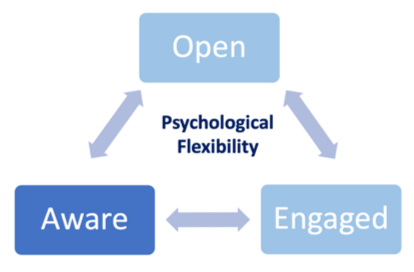

Psychological flexibility is comprised of several processes (Ciarrochi et al., 2010). This fact sheet is the second in a series of three fact sheets. It addresses the skill of being aware; the other two address being open and being engaged.

Uncertainty and worry can be a common struggle for many people, whether they are uncertain about their jobs, health, or relationships. Events such as COVID-19 and the recent wars in Israel and Ukraine increase the stress and uncertainty many people face. Such uncertainty can lead to increases in both mental and physical health concerns (Freeston et al., 2020).

Awareness, a fundamental part of psychological flexibility, can help individuals maintain a high quality of life—even when experiencing uncertainty and mental health concerns—by helping them connect with the present moment and their inner self (Hayes et al., 2020). Developing awareness can benefit individuals from various backgrounds experiencing disruptive events (Korska et al., 2020; Wąsowicz et al., 2021).

Skill Overview: Cultivating Awareness

Being aware involves:

- Intentionally observing thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations without trying to change or judge them.

- Learning to connect with the current moment or being focused on what’s happening now rather than focusing on the past or future.

- Mindfulness exercises, such as meditation or grounding. These exercises are a great way to develop awareness (Hayes et al., 2012; Hayes, 2020).

Application and Practice: Cultivating Awareness

Mindfulness Exercises

Developing awareness requires regular practice and patience. Start by setting aside a few minutes each day to engage in mindful observation.

- Get comfortable - Find a quiet space where you can sit or lie down. Close your eyes to minimize distractions.

- Focus - Pay attention to your breath. Notice its rhythm as you breathe in and out.

- Observe - Begin noticing thoughts as they come and go. Instead of getting caught up in any particular thought, practice viewing the thought from a neutral or detached standpoint, or in other words, acknowledge the thought’s presence without judging the thought.

- Expand - Expand your focus to notice the emotions or physical sensations that arise. Allow yourself to experience and reflect on these sensations without trying to change them or push them away.

Embrace Imperfection

- Maintaining focus and eliminating distractions is very challenging! Be gentle with yourself and remember that your aim shouldn’t be perfection—your aim is just increased awareness.

- If your mind wanders, that’s okay! Acknowledge the thought before gently redirecting your attention back to what you’ve chosen to focus on, whether it's your breath or another anchor.

Deepen Your Awareness

- Over time, you can integrate awareness into daily activities, such as eating, walking, or engaging in conversations. For example, you can try to pay careful attention to the textures, temperatures, and flavors of your breakfast. Or, you can work on listening to what people are saying and waiting until they finish before coming up with a response. Notice, without judgement, the sensations, thoughts, and emotions that you experience.

- Seek additional resources on mindfulness to deepen your understanding and continue your journey toward enhanced awareness. There are many free apps you can download and helpful videos available for free on YouTube. Try these out and find what works for you.

Storytelling

We are always creating stories! It’s how we make sense of ourselves and the world around us (Hayes, 2020). Often, these stories aren’t true or useful for who we want to be. However, when we believe in these stories, we give them power. In fact, we will often act based on the stories we tell ourselves, even if our values tell us to act another way (Davis et al., 2021a).

The stories we tell ourselves can be complex. They may include specific childhood experiences and previous interactions that shape how we will react in specific situations. Or, our stories can be as simple as “I am a smart person,” “I am an angry person,” or “I am an anxious person” (Davis et al., 2021a). As described in the related fact sheet in this series titled, “Skills to Support Mental Health in Uncertain Times: Being Open,” we can acknowledge these stories as thoughts, and allow them to come and go. We can also engage with our stories and practice telling them differently (see the following example).

Example

- Sally has Long COVID. While Long COVID can look different for everyone (Koc et al., 2022), Sally experiences Long COVID’s more common symptoms—fatigue and cognitive impairment (Davis et al., 2021b). A story she started telling herself is, “Because I have Long COVID, I’m not as smart as I used to be, and I can’t do as much as I used to be able to do.” After meeting with her therapist, Sally chose to try rewriting this story:

- “Because I have Long COVID, I need to figure out new, more efficient ways to get my work done.”

- “I have Long COVID. Long COVID makes tasks that require concentration more difficult.”

- “I have Long COVID because my body fought really hard to beat a deadly virus. Now, I must keep fighting hard to live the life I want to live.”

- Alternatively, you can write a story about someone else facing similar circumstances as you (Davis et al., 2021a). For example, Sally is a huge Sherlock Holmes fan. She imagines Sherlock has Long COVID and creates stories about how this impacts his day-to-day life and crime-solving. This can help her see her own story in a new light.

When rewriting a story, the point is not to put a positive spin on the narrative. The purpose of rewriting a story is simply to help you recognize the power that story has in influencing your actions (Hayes, 2020). When you learn to recognize the stories that are preventing you from living the way you want to live, and when you can rewrite those stories, you can act in a more flexible, values-driven way.

Practice

What is a story about yourself that prevents you from doing the things you want to do? Write that story down. Then, rewrite that same story three different ways (keep the main facts the same and change the implications or outcomes). Keep rewriting that story until you take away the power you gave it to determine your actions.

For more information about psychological flexibility and to access additional skill-building exercises, see the website Steven C. Hayes, Ph.D. To focus specifically on becoming more aware, scroll to the ACT Tools section on this webpage and look at the “Presence” and “Self” exercises.

References

-

Ciarrochi, J., Bilich, L., & Godsell, C. (2010). Psychological flexibility as a mechanism of change in acceptance and commitment therapy. In R. Baer (Ed.), Assessing mindfulness and acceptance: Illuminating the processes of change (pp. 51–76). New Harbinger Publications.

-

Davis, C. H., Gaudiano, B. A., McHugh, L., & Levin, M. E. (2021a). Integrating storytelling into the theory and practice of contextual behavioral science. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 20, 155–162.

-

Davis, H. E., Assaf, G. S., McCorkell, L., Wei, H., Low, R. J., Re'em, Y., Redfield, S., Austin, J. P., & Akrami, A. (2021b). Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine, 38.

-

Freeston, M., Tiplady, A., Mawn, L., Bottesi, G., & Thwaites, S. (2020). Towards a model of uncertainty distress in the context of Coronavirus (COVID-19). The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 13, e31.

-

Hayes, S. C. (2020). A liberated mind: How to pivot toward what matters. Penguin.

-

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K., & Wilson, K. G. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

-

Koc, H. C., Xiao, J., Liu, W., Li, Y., & Chen, G. (2022). Long COVID and its management. International Journal of Biological Sciences, 18(12), 4768.

-

Wąsowicz, G., Mizak, S., Krawiec, J., & Białaszek, W. (2021). Mental health, well-being, and psychological flexibility in the stressful times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 647975. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647975

Published December 2023

Utah State University Extension

Peer-Reviewed Fact Sheet

Authors

Heather Kelley, Rachel Byers, Ty Aller, and Tim Keady

Related Research