Small Hive Beetle

[Aethina tumida (Murray)]

June 2018

Lori Spears, Extension Entomologist (No longer at USU) • Ann Mull, Extension Assistant (No longer at USU)

Quick Facts

- The small hive beetle (SHB) is an exotic pest of honey bee and bumble bee colonies and can have a significant impact on apiculture and wild bee populations.

- SHB can be found in much of the U.S., including Utah, but it is more common in the Southeast.

- SHB spreads primarily by movement of bees, bee products, and beekeeping equipment.

- Infested hives appear slimy and have an odor resembling that of rotten oranges.

- SHB infestations can be prevented by early detection, using good husbandry techniques, maintaining a high ratio of bees to comb, and keeping hives in partial to full sun.

- Chemical control options for SHB are limited due to toxicity to bees.

- Coumaphos strips placed in the bottom of hives can reduce SHB infestations.

Fig. 1. Small hive beetles (SHB) in a honey bee hive. Image courtesy of Jessica Louque, Smithers Viscient, Bugwood.org.

Small hive beetle [Aethina tumida (Murray)] (SHB) (Order Coleoptera, Family Nitidulidae) (Fig. 1) is an exotic pest of social bee colonies, including honey bees (Apis mellifera) and bumble bees (Bombus spp.). SHB will feed on pollen and honey, and kill bee brood and workers. Their frass (feces) causes honey to discolor, ferment, and froth. Infested hives can appear slimy, drip fermented honey, and have a rotten orange odor that is repellent to bees and attractive to SHB. Under heavy infestations, bee colonies can quickly collapse. Queens stop laying eggs, and the heat generated by large numbers of SHB larvae can cause comb collapse and colony abandonment. SHB is largely spread through packaged bees, beekeeping equipment, and bee products, but adults are strong fliers and can easily disperse to new hives.

SHB is native to sub-Saharan Africa where native African honey bee (Apis mellifera scutellata) behaviors, such as elevated aggression levels, can limit SHB infestations. SHB has been detected in many countries, including Canada and Mexico, and was first detected in the U.S. in South Carolina in 1996. SHB is now found throughout much of the U.S., including Hawaii, with highest infestations occurring in the Southeast. It was first found in Utah in 2016, and is now confirmed in Washington and Davis counties.

Suspect SHB can be sent to the Utah Plant Pest Diagnostic Lab at Utah State University or the Utah Apiary Program at Utah Department of Agriculture and Food. Specimens should be placed into a vial containing rubbing alcohol (white vinegar or hand sanitizer are suitable alternatives) and secured using packing material to avoid damage.

Description

Adults are small, 1/4 inch (5-7 mm) long and 1/8 inch (2.5-3.5 mm) wide, flattened beetles that are oblong in shape, with clubbed antennae and shortened elytra (hard wing coverings) (Fig. 2). Females are generally larger than males. Their color ranges from reddish-brown to dark brown (almost black) and darkens with age. Note that the dusky sap beetle (Carpophilus lugubris) is a similar-looking beetle (Fig. 3) and has been found in a few honey bee hives in Utah. However, the dusky sap beetle is a scavenger, attracted to decaying fruit and vegetables, and is currently not known to impact honey bee colonies. SHB eggs are 1/16 inch (1.4 mm) long, creamy white in color, and only 2/3 the size of honey bee eggs (Fig. 4).

Mature larvae are 3/8 inch (9.5-11 mm) long and 1/16 inch (1.6 mm) wide, pearly white to beige in color, and have three pairs of legs near the head (Figs. 4-6). They have distinctive rows of body spines, and two large spines protruding from the rear. The SHB larva looks similar to the wax moth larva (Galleria melonella), but on close examination can be distinguished by their body spines and by only having three pairs of legs near the head. Wax moth larvae have additional four pairs of less developed abdominal legs, lack body spines, and can grow to double the size of SHB larvae (Fig. 6). Further, wax moth larvae produce webbing in combs and can be found scattered throughout the hive; SHB produces no webbing and often congregate in corners.

Pupae are 1/4 inch (5 mm) long and creamy white to light brown in color, but darken with age.

Life History

SHB overwinters as adults and can be found amid the honey bee cluster where it is warm. Egg-laying occurs when temperatures are between 60-112°F (Annand 2011). Females typically lay eggs in clusters of 10-30 in cracks and crevices of the hive, under sealed brood cells, or in capped honey bee worker brood. A single female can lay up to two thousand eggs in her lifetime.

Eggs hatch in 2-6 days, and then the larvae feed for 3-14 days, tunneling through comb to eat bee eggs and brood, honey, and pollen. Tens of thousands of larvae may be present within a single hive, with up to 30 larvae per cell. When larvae reach their post-feeding stage (“wandering stage”), they become attracted to light. They congregate on the bottom board and in frame corners, eventually exiting colonies typically en masse at dusk, in search of suitable pupation substrates. They are capable of migrating more than 200 yards (183 m) and can exist in this stage without feeding for up to 60 days.

Pupation usually occurs within a 20-yard (18 m) radius in the top 4 inches (10 cm) of the soil around the hive, and lasts 2-12 weeks, depending on environmental conditions. Soil moisture is essential for successful pupation; developmental time is shorter in warm (above 62-77°F) (17-25°C), moist, non-compacted soils. Following pupation, adults leave the soil and invade bee colonies individually or in swarms and are attracted by the odors emitted by host colonies. They can fly up to 10 miles (16 km) searching for new host colonies. Adults live an average of 4-6 months, but can survive up to 16 months. As many as six generations per year can occur under moderate environmental conditions.

Prevention

There is no established treatment threshold for SHB, but if large populations are allowed to build up, a bee colony can collapse in under 10 days. Therefore, the most effective control method is prevention through ensuring that bee colonies are strong and healthy so that they can better defend themselves against SHB attack. Use the following tactics to safeguard your hives:

Fig. 2. SHB adults have clubbed antennae (left), but are often observed in the hive with their head and antennae tucked under their body (right). Image courtesy of The Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA), Crown Copyright, nationalbeeunit.com (left image); Natasha Wright, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Bugwood.org (right image).

Fig. 3. Dusky sap beetle, a SHB lookalike, on an overripe melon. Image courtesy of Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org.

Fig. 4. SHB eggs (circled) ad larvae. Image courtesy of Jessica Louque, Smithers Viscient, Bugwood.org.

Fig. 5. SHB larvae. Image courtesy of James D. Ellis, University of Florida, Bugwood.org.

Fig. 6. SHB larvae (main image) have three pairs of legs near the head, two large spines projecting from their rear (see arrows), and body spines; wax moth larvae (inset) have abdominal legs (see arrow) and lack rear and body spines. Image courtesy of Pest and Diseases Image Library, Bugwood.org (main image); Susan Ellis, USDA APHIS PPQ, Bugwood.org (inset).

- Place hives in partial to full sun.

- Keep soil under hives dry to deter SHB pupation.

- Combine, eliminate, or re-queen weak colonies.

- Clean hives and frames, and maintain in good condition to decrease beetle hiding sites.

- Avoid over-supering hives. Having too many boxes gives beetles excessive space to move, hide, and lay eggs.

- Reduce stresses from other bee pests and diseases.

- Ensure that all colonies sent/received are free of SHB.

- Keep a high ratio of bees to comb to prevent SHB from hiding from patrolling bees. Similarly, take care when splitting hives to have sufficient numbers of bees present in each split.

- If using a non-screen bottom board, regularly remove the accumulating debris to prevent SHB from pupating inside the hive.

- Maintain a clean extraction facility and equipment storage room with humidity levels <50%.

- Process honey within 1-2 days following removal from the colony, clean area thoroughly afterward, and avoid leaving wax cappings and other bee products lying around. If you suspect a SHB infestation, prior to extracting honey, freeze honeycomb at 10°F (-12°C) for at least 12 hours to kill beetle life stages.

- Avoid using grease patties for mite control or adding protein patties for spring buildup. These are attractive to SHB and may increase chances of infestation.

Detection

Regular hive inspection is necessary for early detection. Ideally, hives should be inspected once or twice a month, especially during spring and summer.

Use a flashlight to visually inspect hives. Adults actively seek dark areas of the hive and will scurry away from light when the hive is opened for inspection. When opening the hive, look for SHB adults running across the combs, crown boards, and the hive floor. Their heads may be tucked downward, so their clubbed antennae may not be readily visible (Figs. 1,2). During warm weather, SHB adults will generally be on the hive floor; in cooler temperatures, look for them among the clustering bees. Also check cracks and crevices for egg clusters, and check combs and the bottom board for larvae (Figs. 4,5).

Alternatively, during sunny conditions, the top super of a hive can be placed on the hive lid for about 10 minutes. The sunlight will force the adults to the bottom of the super and onto the lid. When the super is lifted, the beetles can then be more easily observed.

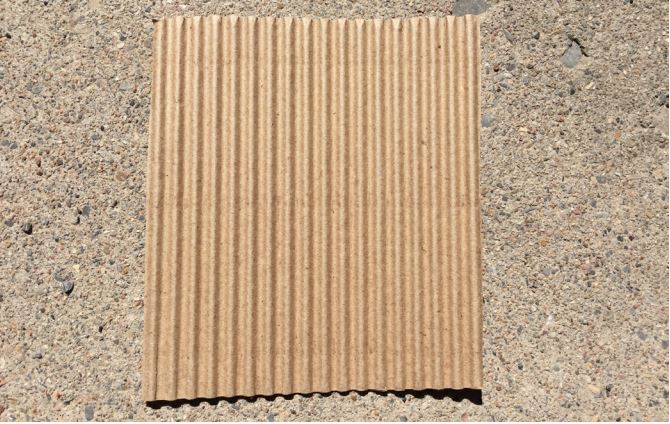

Consider placing 4-mm thick corrugated plastic or cardboard strips with the corrugated side down on the bottom board near the back of the hive to further aid in detecting SHB. You may need to remove the paper from one side to expose the corrugations. The opposite and upward facing side should be covered with tape (Fig. 7) to prevent the bees from destroying and then removing the cardboard from their hive. Regularly inspect the debris under the insert for evidence of SHB.

Infested colonies may have fermented honey dripping from hive entrances, damaged and slimy combs, and dark, crusty traces that appear on the hive exterior from wandering larvae (Figs. 5,8). Heavily infested colonies typically smell like decaying oranges.

Fig. 7. Corrugated cardboard insert to detect SHB.

Fig. 8. Damage to honey bee hive. Image courtesy of Jessica Louque, Smithers Viscient, Bugwood.org.

Management

Traps: Traps can be used to remove SHB from hives. Most traps work by drowning beetles in oil or soapy water. The traps that have been shown to be effective at controlling SHB include the commercially available Freeman Beetle Trap (Fig. 9), West Trap, Beetle Blaster, and Hood Trap, as well as the homemade Sonny-Mel Trap. See Zawislak Page 4 (2014) for detailed descriptions of traps.

Fig. 9. The Freeman Beetle Trap consists of a screened mesh bottom board and a plastic tray filled with cooking oil or soapy water and slid underneath the screened mesh. Guard bees will pursue the beetles, which then fall into the liquid and die. Image courtesy of DML. http://www.honeybees-by-the-sea.com/freeman1.htm .

Biological Control: Entomopathogenic nematodes (EPNs) (e.g., Steinernema carpocapsai, S. kraussei, S. riobrave, and Heterorhabditis indica) can be an effective management strategy against wandering larvae and pupae. EPNs are commercially available and can be placed in the soil surrounding the hive where SHB pupates. However, applications should be made when temperatures are between 50-68°F (10-20°C), and annual applications may be necessary since some EPNs may be unable to overwinter and persist in Utah’s climate. The use of entomopathogenic fungi (Metarhizium, Lecanicillium, and Beauveria) for SHB control is another option, but studies have had mixed results, which suggests that more work is needed to determine their efficacy and feasibility in Utah’s climate.

Biopesticides: Diatomaceous earth or slaked lime (also known as hydrated lime or calcium hydroxide) may be effective against SHB. These agents can be applied to the soil surrounding the hive (to limit SHB pupation success) or placed in trays on the bottom board of the hive box (to control adult SHB within the hive).

Chemical Control: Chemical control should be used only as a last resort. Chemicals used to control SHB are highly toxic to bees and may lead to death of the hive and/ or chemically-resistant SHB populations. Gard Star® is a permethrin product which, applied as a soil drench, can be used to kill wandering larvae, pupae, and emerging adults in late spring or when the weather is warm enough for them to complete their life cycle. Before application, vegetation surrounding the hive should be mowed so that the chemical can directly contact the soil. Gard Star® must not be used inside the hive! Application should only be made in the evening when few bees are outside the hive. Always read and follow the label directions before applying any pesticide.

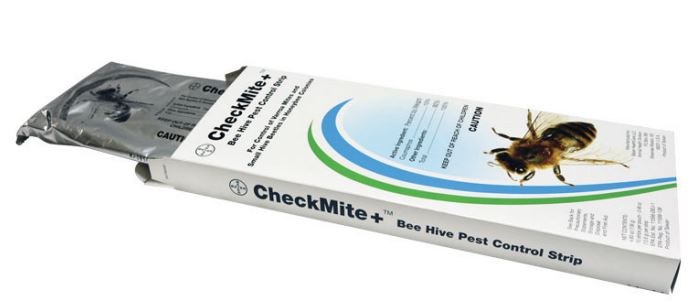

Checkmite+™ strips (active ingredient: coumaphos) (Fig. 10) is the only product registered for SHB control inside the hive. Staple the strips to corrugated cardboard squares and then place the squares on the bottom board of the hive with the insecticide strip facing down. The beetles come into contact with the strips when they seek cover under the cardboard. Remove strips after 42-45 days. Honey supers should be removed before using the chemical strips to avoid honey contamination, and then replaced 2 weeks after strip removal from the hive.

Fig. 10. Checkmite+™ strips. Image courtesy of Mann Lake, www.mannlakeltd.com/checkmite-trade-10-pack.

Supply Sources

Arbico Organics

Oro Valley, AZ

(800) 827-2847

Dadant

Hamilton, IL

(800) 922-1293

Mann Lake

Hackensack, MN

(800) 880-7694

Sources for Entomopathogenic Nematodes and Fungi

Arbico Organics

Oro Valley, AZ

(800) 827-2847

Rincon-Vitova Insectaries

Ventura, CA

(800) 248-2847

References and Further Reading

- Annand, N. 2011. Investigations on small hive beetle biology to develop better control options. M.S. thesis. Univ of Western Sydney. 146 pp.

- Bernier, M., Fournier, V., and Giovenazzo, P. 2014. Pupal development of Aethina tumida (Coleoptera: Nitidulidae) in thermo-hygrometric soil conditions encountered in temperate climates. Journal of Economic Entomology 107: 531-537.

- Buchholz, S., Merkel, K., Spiewok, S., Pettis J.S., Duncan, M., Spooner-Hart, R., Ulrichs, C., Ritter, W., and Neumann, P. 2009. Alternative control of Aethina tumida Murray (Coleoptera: Nitidulidae) with lime and diatomaceous earth. Apidologie 40: 535-548.

- Cornelissen, B. (A.C.M.) and Neumann, P. 2018. How to catch a small beetle: Top tips for visually screening honey bee colonies for small hive beetles. Bee World, DOI: 10.1080/0005772X.2018.1465374

- Cuthbertson, A.G.S., Mathers, J.J., Blackburn, L.F., Powell, M.E., Marris, G., Pietravalle, S., Brown, M.A., and Budge, G.E. 2012. Screening commercially available entomopathogenic biocontrol agents for the control of Aethina tumida (Coleoptera: Nitidulidae) in the UK. Insects 3: 719-726.

- Cuthbertson, A.G.S., Wakefield, M.E., Powell, M.E., Marris, G., Anderson, H., Budge, G.E., Mathers, J.J., Blackburn, L.F., and Brown, M.A. 2013. The Small hive beetle Aethina tumida: A review of its biology and control measures. Current Zoology 59: 644-653.

- Elzen, P.J., Baxter, J.R., Westervelt, D., Randall, C., Delaplane, K.S., Cutts, L., and Wilson, W.T. 1999. Field control and biology studies of a new pest species, Aethina tumida Murray (Coleoptera, Nitidulidae), attacking European honey bees in the Western Hemisphere. Apidologie 30: 361–366.

- National Bee Unit. 2017. The small hive beetle: a serious threat to European apiculture. Animal and Plant Health Agency. Crown copyright.