Public Health Violence Prevention: Supporting Law Enforcement

Can Public Health Efforts Reduce Crime and Resolve Inequities?

As frustrations over inequalities in policing and law enforcement continue despite attempted reforms (Beckett, 2016), many are asking for a more effective approach. A 2018 issue statement from the American Public Health Association

(2018) highlights that violence is a public health issue that will not go away without the influence of a public health approach. The integrated biological-psychological-social model of health recognizes the complexity in the ways individuals are influenced by their situations, with violence as the unfortunate result of the wrong mix of circumstances. The public health approach to violence focuses on prevention as part of the solution. We are now more than three decades past the Surgeon General Koop’s call to action to incorporate public health perspectives into violence prevention (Koop, 1985) and can look back on how far we have come and how far we still need to go.

What Is the Public Health Approach?

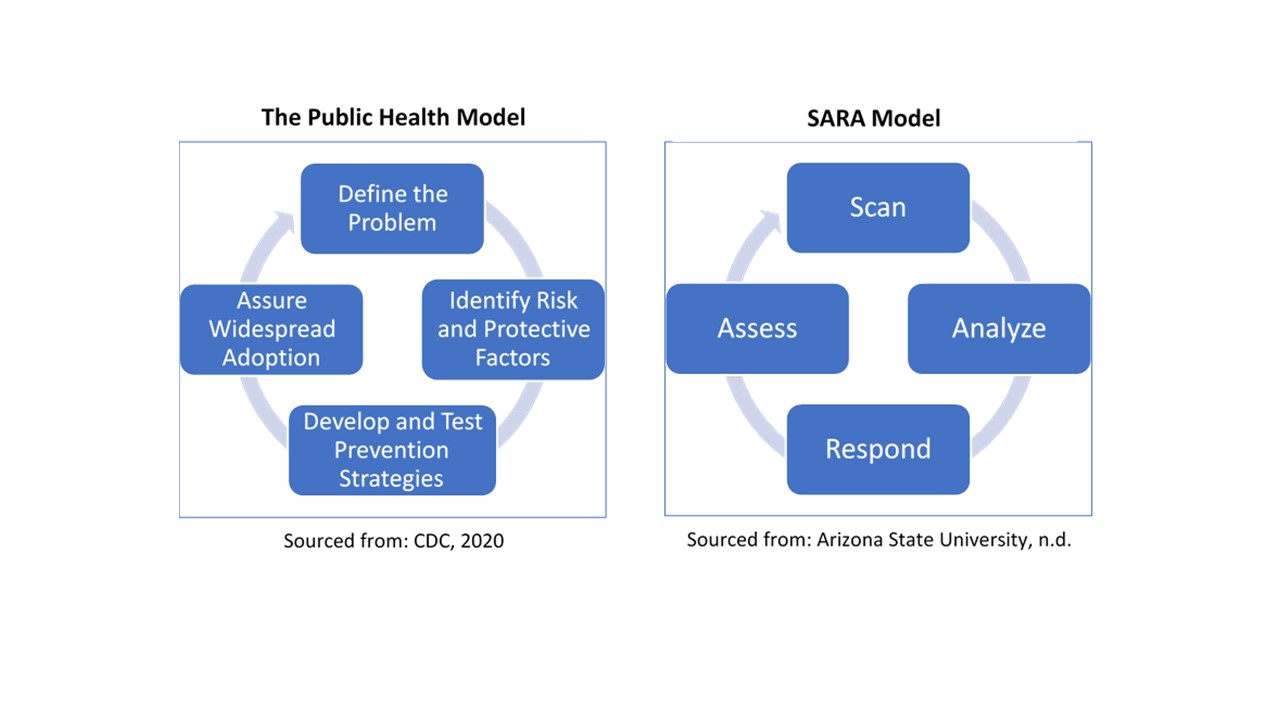

Public health uses a prevention approach to address issues related to violence, whereas the criminal justice field traditionally relies on a more reactive approach to address violence.Throughout the years, law enforcement and public health have combined efforts to address the health of the communities they serve. Indeed, law enforcement and public health have similar models for addressing needs (Markovic, 2012).

The public health model has four steps: (1) Define the problem; (2) Identify risk and protective factors; (3) Develop and test prevention strategies; and (4) Assure widespread adoption (CDC, 2020). Likewise, law enforcement utilizes the SARA model (Arizona State University, n.d.), which stands for:

- Scan different sources to identify the problem.

- Analyze data to learn more about the problem.

- Respond with a chosen intervention based on results found.

- Assess implementation and whether intended outcomes were achieved.

While both models assess the problem or situation before developing a strategy and responding, the interventions can look very different. These differences stem from the lens used to view the problem and analyze potential solutions. For example, a criminal justice approach tends to emphasize the differences between predators and victims (Beckett, 2016). A public health perspective emphasizes commonalities through shared risk and protective factors. A criminal justice approach may lead to prosecutions and incarcerations. A public health approach may emphasize prevention programs, social supports, and case management.

Public health workers are trained to address the disparities and stressors that may lead to violence and can offer support to the approaches of law enforcement, first responders, and criminal justice systems. There are increasingly combined efforts between public health and law enforcement that can keep crime in check while acknowledging the bio-psycho-social drivers of behavior. For example, the criminal justice system has employed prevention tactics in the juvenile justice system to deter young offenders, adopted community policing to support communities, and used problem-solving policing tactics (Moore et al., 1993). These prevention efforts include recent adoption of criminal justice reform, drug courts, and mental health courts.

Community policing policies have been adopted by 90% of police departments since the 1990s, with a focus on relationships and dialogue and building goodwill between community members and law enforcement (Skogan, 2006a). Participatory community action approaches take these efforts one step further, encouraging communities to take charge of the problems

as they see them, and leveraging community organizing and group empowerment to secure positive outcomes. In this model, police officers can implement these public health ideas alongside community members, wherein the message of policing is less about enforcement and more about supporting community needs (Skogan, 2006b).

What Are the Benefits of Incorporating Public Health Strategies?

Financial Benefits

Cost Reductions and Savings―$5.60 Saved for Every $1 Invested

In an economy where funding is scarce, and many agencies are having to do more with less, combining efforts offers a win-win opportunity. We know that public health expenditures can save money for communities. For example, it is estimated that in the U.S., every $1 spent per person, per year, translates to a potential savings of $5.60, and $10 spent per person on public health programming can have a return of over $16 billion within five years (America’s Health Rankings Analysis, 2020). Research also indicates that these public health interventions can measurably reduce criminal justice costs (Wilkins et al., 2014).

A report of 46 states’ expenditures on youth confinement found an average annual cost of

$150,000 per youth (Petteruti, Schindler, & Ziedenberg, 2014). One method of reducing these costs through public health efforts is engaging youth in violence-prevention programs that reduce risk factors and increase protective factors (Wilkins et al., 2014). Regular home visits to low-income, first-time mothers by trained nurses resulted in half the arrest rate by age 15 compared to youth not involved in the program, and $4 saved for every $1 invested (Prevention Institute, 2012).

Community Benefits

Communities that Feel Safer

Communities that Feel Safer Communities that have fewer protective factors can be more likely to suffer from violence

(Wilkins et al., 2014). Neighborhoods with low cohesion and trust are more likely to experience child maltreatment, partner violence, and youth violence. Conversely, one of the protective factors that increase a community’s resilience to violence includes coordination of resources and services among agencies (Wilkins et al., 2014).Partnered public health and law enforcement can increase coordination and community cohesion (see the FIT program below).

Human Benefits

Reduced Exposure to Violence

Direct and indirect exposure to violence has been associated with outcomes like depression, anxiety, and suicide (Tublitz & Lawrence, 2014). When community members feel unsafe, studies have shown an increase in stress, anxiety, and depression. Parents may have concerns about letting their children play outside, and community members may be less motivated to exercise outdoors or use community parks when they don’t feel safe in their communities. People may be less likely to travel farther for healthy foods and may rely primarily on convenience stores carrying less healthy options (Egerter, 2011).

Better Health for Community Members and First Responders

Taking a public health approach against violence and crime can help reduce the frequency and severity of chronic disease and negative mental health outcomes (Wilkins et al., 2014). This health boost occurs for both the public and first responders. Law enforcement who face constant demands from the public they serve without the resources to be effective within their communities face higher levels of mental stress and burnout as well (McCarty et al., 2019). Taking a public health approach against violence and crime can help prevent burnout in first responders (Reynolds & Wagner, 2008).

Examples of Success

One example of successfully utilizing public health interventions to reduce crime is the Housing First model, launched in Utah in 2005. This program places people in housing before requiring sobriety, treatment, employment, or other stipulations

(Scruggs, 2019). The first decade of the program was hugely successful, with a 91% drop in chronic homelessness. This was credited to the fact that a substantial portion of the chronically unhoused face significant health or mental health challenges, which can lead to a cycle of policing for petty crimes such as loitering or disturbing the peace. It has been argued that police efforts spent on this group do little to decrease overall crime. Rather, a high homeless population may actually contribute to increased crime in an unexpected way because the unhoused are more likely to be victims of crime (Scurggs, 2019). When funding ended for the Housing First program after ten years, the number of people sleeping outdoors doubled within three years.

Another example comes from the Fitness Improvement Training (FIT) Zone program in East Palo Alto, CA. Its purpose was to increase residents’ use of outdoor spaces, primarily in areas that saw gun violence and gang activity. The idea was that residents in a community who are active and use outdoor spaces might deter criminal activity, helping them reclaim their shared spaces (Schweig, 2014). An evaluation of the program found that shootings decreased by 27%-58%

in one of the two FIT Zones. It was also found that offenders did not “move” to another area, with positive effects extending beyond the zone (Tublitz & Lawrence, 2014).

A pilot program conducted in Cardiff, Wales made it possible for law enforcement to determine hot spots needing particular attention. This arose from the discrepancy between hospital visits from persons injured by violence and the number of calls made to police reporting such crimes. This collaboration between health inputs and emergency services led to recommended changes in the community to increase safety, such as increasing nightly public transportation routes and improved street lighting (Markovic, 2012).

What Needs to Happen?

Bringing Public Health and Law Enforcement Together

Cross-Agency Partnerships

Public health and law enforcement have a lot in common. Both sectors want to improve the health and safety of their communities and to stamp out violence (Wolf, 2012). Coordinating the efforts of the two sectors can bring a balance of prevention and reaction approaches, which are customizable behavioral changes to the specific community

(Moore et al., 1993). The American Public Health Association (APHA) called for the government at every level to “adopt, invest in, expand, and support evidence-based and promising public health approaches to violence prevention”

(APHA, 2018). Critical issues for public health and law enforcement to collaborate on are prevention methods, information, data analysis, accountability, and cost.

Sharing Data

Like the Cardiff project, when public health and law enforcement combine efforts and share data, there can be an improved community response. Examples include multidisciplinary case reviews (Milwaukee’s Homicide Review Commission); multiuser interactive mapping (Los Angeles’ Community-Based Information System); tracking high crime areas (Palo Alto’s FIT Zones); social network analysis (New Haven’s Project Long); and environmental improvement initiatives (Philadelphia’s PhillyRising) (Markovic, 2012; Joyce & Schweig, 2014). Agencies’ data sharing has enabled an enhanced ability to address the societal, socioeconomic, and environmental causes of violence.

Funding Appropriations

As evidenced in the Housing First program in Utah, public health programs that stem crime and violence require funding. The White House budget fact sheet indicates law enforcement received a 2.4% funding increase from 2017 to 2019 (White House 2019 Budget Fact Sheet, n.d.). The document cites investments in addressing the opioid epidemic, prisoner re-entry programs, and violence against women, among other initiatives. Conversely, public health is seeing relative declines in its budget compared to overall healthcare spending. Public health funding hit a peak of 3.18% of all funds spent on healthcare in 2002 and has been falling ever since, down to 2.65%, and is projected to continuing falling to 2.4% by 2023 (Himmelstein & Woolhandler, 2016).

References

- America’s Health Rankings, United Health Foundation. (n.d.). Analysis of trust for America’s health, annual estimates of the resident population: April 1, 2010, to July 1, 2018. U.S. Health and Human Services, U.S. Census Bureau. Americashealthrankings.org

- American Public Health Association. (2018, November 13). Violence is a public health issue: Public health is essential to understanding and treating violence in the U.S. (Policy Number 20185). https://www. apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2019/01/28/violence-is-a-public-health-issue

- Arizona State University. (n.d.). The SARA Model. ASU Center for Problem-Oriented Policing. https://popcenter.asu.edu/content/sara-model-0

- Beckett, K., Reosti, A., & Knaphus, E. (2016). The end of an era? Understanding the contradictions of criminal justice reform. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 664(1), 238–259.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). The public health approach to violence prevention. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/publichealthissue/publichealthapproach.html

- Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (2018). American health care: Health spending and the federal budget. https://www.crfb.org/papers/american-health-care-health-spending-and-federal-budget

- Egerter S., Barclay C., Grossman-Kahn R., & Braveman P. (2011). Violence, social disadvantage, and health. In Exploring the Social Determinants of Health (Issue Brief No. 10). Princeton: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF). http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc download;jsessionid= 7999102D5BC386B04645E90EC5870CD2 ?doi=10.1.1.654.3851&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Himmelstein, D. U., & Woolhandler, S. (2016). Public health’s falling share of U.S. health spending. American Journal of Public Health, 106(1), 56–57.

- Joyce, N. & Schweig, S. (2014). Preventing victimization: Public health approaches to fight crime. The Police Chief Magazine, 38–41.

- Koop, C. (1985). Welcome and “charge” to the participants. Surgeon General’s Workshop on Violence and Public Health. Health Resources and Services Administration; U.S. Public Health Service; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS Publication No. HRS-D-MC 86-1).

https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/confrontingviolence/materials/OB10998.pdf. - Markovic, J. (2012). Criminal justice and public health approaches to violent crime: complementary perspectives. Geography and Public Safety, 3(2), 1–18. https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=720049

- McCarty, W. P., Aldirawi, H., Dewald, S., & Palacios, M. (2019). Burnout in blue: An analysis of the extent and primary predictors of burnout among law enforcement officers in the United States. Police Quarterly, 22(3), 278–304. DOI:10.1177/1098611119828038

- Moore, M. (1993). Violence Prevention: Criminal Justice Or Public Health? Health Affairs, 12(4), 34-45. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.12.4.34

- Petteruti, A., Schindler, M., & Ziedenberg, J. (2014). Calculating the full price tag for youth incarceration. Justice Policy Institute. http://www.justicepolicy.org/uploads/justicepolicy/documents/sticker_shock_final_v2.pdf

- Reynolds, C., & Wagner, S. (2008). Stress and first responders: The need for a multidimensional approach to stress management. International Journal of Disability Management, 2(2), 27–36.

- Schweig, S. (2014). Healthy communities may make safe communities: Public health approaches to violence prevention. National Institute of Justice, 273, 52–59.

- Scruggs, G. (2019). Once a national model, Utah struggles with homelessness. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-homelessness-housing/once-a-national-model-utah-struggles-with-homelessness-idUSKCN1P41EQ

- Skogan, W. G. (2006a). Advocate: The promise of community policing. Police Innovation: Contrasting Perspectives, Cambridge University Press, 27–43. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511489334.002

- Skogan, W. G. (2006b). Police and community in Chicago: A tale of three cities. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 1(2), 244–245.

- Trust for America’s Health. (2020). The impact of chronic underfunding of America’s public health system: Trends, risks, and recommendations, 2019. (Executive Summary). https://www.tfah.org/report-details/2019-funding-report/

- Tublitz, R. & Lawrence, S. (2014). Public safety impacts of a public health intervention: Assessing east Palo Alto’s Fitness Improvement Training Zone program. University of California Berkeley School of Law. Research Brief. https://www.law.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Public-Safety-Impacts-of-a-Public-Health-Intervention-FINAL.pdf

- Prevention Institute. (2012). Public health contributions to preventing violence [Fact sheet]. https://www.preventioninstitute.org/sites/default/files/publications/Public%20Health%20Contributions%20 to%20Preventing%20Violence.pdf

- White House 2019 Budget Fact Sheet. (n.d.). Strengthening the criminal justice system: An American budget. U.S. Department of Justice, Criminal Justice. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/FY19-Budget-Fact-Sheet_Criminal-Justice-Reform.pdf

- Wilkins, N., Tsao, B., Hertz, M., Davis, R., & Klevens, J. (2014). Connecting the dots: An overview of the links among multiple forms of violence. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA; Prevention Institute: Oakland, CA.

- Wolf, R. V. (2012). The overlap between public health and law enforcement: Sharing tools and data to foster healthier communities. International Review of Law, Computers & Technology, 26(1), 97–107. DOI:10.1080/13600869.2012.646802

Authors

Kira Swensen, Gabriela Murza, Sandy Sulzer, Maren Voss

Related Research