Oaks in the Landscape

Introduction

Oak trees (Quercus sp.) are generally a tough, drought tolerant, and beautiful addition to Utah landscapes. There are roughly 450 known species of oak, with about 60 varieties native to North America (Dirr, 2009). Trees vary in size and shape, from the native shrub-like Gambel oak (Quercus gambelii) to large and stately shade trees like the northern red oak (Quercus rubra). Oaks are known for slow to moderate growth, sturdiness, and easy care and can be used to create a focal point and ornamental interest in the landscape.

Fall color is typically not brilliant but can provide various shades of red, orange, yellow, and brown. Generally speaking, oak tree leaves can be persistent, meaning that they are retained on the tree throughout the winter, providing shelter for many varieties of birds and different wildlife. As leaves emerge in the spring, the retained leaves will drop.

Trees produce yellow to green catkins in the spring, producing fruits called acorns when pollinated. Acorns add another layer of texture and interest to the landscape and can provide food for wildlife but can be considered messy in the fall.

Recommended Cultivars

When selecting an oak for your landscape, consider these factors as you make a decision, including tree size, tree form and shape, fall foliage color, and leaf shape. Oaks have slow to moderate growth and may take many years to grow into a landscape fully, but reward the homeowner with longevity, durability, and elegant stature. Many oaks are adapted to various soils and climate conditions and should perform well. This fact sheet references several cultivars that are well suited to the Intermountain West, but it is not a comprehensive list. If planting a cultivar not listed here, carefully consider climate adaptability and soil conditions.

Most species of oak trees that thrive in the Intermountain West originate from two main groups of oak: white oak and red oak. White oaks have gray-colored bark and leaves with rounded lobes (Figure 1). Acorns produced by white oak take a single year to mature. Trees originating from the white oak include bur oak, chinkapin oak, English oak, and our native Gambel oak (scrub oak).

Red oaks have darker brown to black-colored bark with more pointed leaf edges (Figure 1). Acorns produced by the red oak are usually larger than those produced by the white oak and take two years to fully mature. Trees originating from red oak generally struggle in high alkaline soil, but those that are the most tolerant and likely to succeed in the Intermountain West include northern red oak and Texas red oak.

Pin oak, along with other oak species, are not well suited to the Intermountain West and will not be discussed here. Understanding tree characteristics, such as size, growth rate, and color, will help determine if a specific cultivar is appropriate for your landscape. For specific recommendations and a quick comparison of trees, see Table 1.

White Oak

White oak (Quercus alba): White oak is an exceptionally large and long-lived tree that makes an ideal shade tree. Fall color can vary from orange to red. White oak is an exceptionally slow grower and will not produce acorns until it reaches maturity, typically when trees are between 50 and 100 years old.

Bur or mossycup oak (Quercus macrocarpa): Bur oak is named for the fringed, bur-like cap found on its acorn (Figure 2). It is native to the eastern United States and as far west as eastern Montana and Wyoming. A tough tree, bur oak tolerates pollution, soil compaction, wind, and can grow in extremely low-water conditions once established. It is well adapted to the Intermountain West climate and dry alkaline soil and does not tolerate flooding or saturated soils. Bur oak is often used as a shade tree because of its large (4- to 10-inch) dark green, deeply lobed leaves with silver undersides. Bur oak can be affected by anthracnose and powdery mildew.

Chinkapin oak (Quercus muehlenbergii): Also referred to as rock oak, or yellow oak, chinkapin oak is native to the eastern and central United States. These large, stately trees are characterized by ash-colored, scaly bark and 4- to 6-inch long green leaves that develop a yellow to orange-brown fall color. Trees do best in well-draining soil and are well adapted to alkaline and clay soils. Trees can be affected by anthracnose. Trees were historically used in the Midwest by early pioneers and settlers to construct thousands of miles of fences, specifically in Ohio, Indiana, and Kentucky.

English oak (Quercus robur): Native to Europe and Western Asia, English oaks are among the most stately of the oaks. These trees have been widely planted in North America since the 1600s. Trunks are typically short and stocky, and canopy shape can vary from broad-spreading to columnar. Leaves are lobed and dark green. Fall color can vary from brown and yellow to red.

Swamp white oak (Quercus bicolor): This tree is known for its exfoliating bark, deep green leaves with silvery undersides, and beautiful yellow fall color (Figure 3). Trees can exhibit symptoms of iron chlorosis in high pH soils.

Turkey oak (Quercus cerris): This is a medium-sized oak native to Western Asia and Europe that develops a pyramidal-shaped canopy as it matures (Figure 4). Insignificant brown foliage in the fall makes this a less showy selection, but the dense canopy makes this an excellent shade tree. ‘Argenteovariegata’ is a cultivar with variegated leaves that can add some extra interest in the landscape.

Gambel oak (Quercus gambelii): Also known as scrub oak or Rocky Mountain white oak, this small tree is native to the foothills of most of the Intermountain West. Its shrubby growth habit makes it ideal for smaller landscapes and can provide some privacy when planted in groupings. Large underground root systems (suckers) can easily regrow when trees are subjected to wildfire but often contribute to unwanted lateral/spreading growth, making removal from the landscape difficult.

Red Oak

Northern red oak (Quercus rubra): A good choice for a shade tree, it is somewhat tolerant of moist (but not constantly wet) soils. The northern red oak has a moderate to fast growth rate and forms a beautiful, rounded canopy. Leaves are 4- to 8-inches long and turn red in the fall. This species can be susceptible to iron chlorosis in high pH soils.

Shingle oak or laurel oak (Quercus imbricaria): The shingle oak has small, light green, unlobed leaves that resemble an English laurel and make this tree distinctly different from many other oaks. It is native to the midwestern United States. The shingle oak is a smaller specimen and makes an excellent parkway or shade tree in residential areas. Leaves turn a yellow-brown in the fall and, like many of other oaks, are persistent through the winter.

Shumard oak (Quercus shumardii): This oak species boasts brilliant red-colored fall foliage. With more shallow roots, this tree is transplanted more easily than some other oak species and can tolerate both wet and dry planting areas.

Texas red oak (Quercus buckleyi): This oak is often included with the Shumard oaks and is becoming more popular in landscapes, although careful attention should be given to the hardiness zone when considering this species. This selection may be difficult to find in local nurseries but may be found through online nurseries.

Sonoran scrub oak or turbinella oak (Quercus turbinella): An evergreen shrubby type of oak, this tree is native to the desert region of the southwest (USDA hardiness zone 7 and higher). It is highly adaptable to different soil types but not hardy in cooler northern climates.

Sawtooth oak (Quercus acutissima): The sawtooth oak is a medium- to fast-growing species. These trees produce an abundance of acorns early in their life, providing an important food source for native turkeys and other wildlife. The leaves are distinct in that they are 3.5 to 7.5 inches in length with bristle-like teeth that resemble a saw.

How to Grow

Site Selection

Oaks grow best in full sun, meaning at least 6 to 8 hours of full sun should be available at the site. Many of these trees are large, and mature tree size should be taken into consideration when planting. In general, plant larger trees away from structures and where roots will not damage underground lines or foundations of structures. Smaller trees and shrubby forms, such as Gambel oak, can be planted closer to structures with careful consideration. Ideally, oak prefer loamy, well-draining soil, though many will adapt to clay soil. It is important to adapt watering schedules for soil type; use more frequent, shorter irrigation events with sandy soil and less frequent irrigation for heavier clay soil.

Site Preparation

Taking time to prepare the planting site properly is important as the tree will occupy the site for many years. Controlling perennial weeds, such as field bindweed, before planting is easier than attempting to control weeds after planting. Because some oak may be sensitive to high pH, a soil test before planting may be beneficial to determine your soil texture, pH, salinity, organic matter and nutrient content before planting. For more information on soil testing, visit the USU Analytical Laboratory.

Planting and Spacing

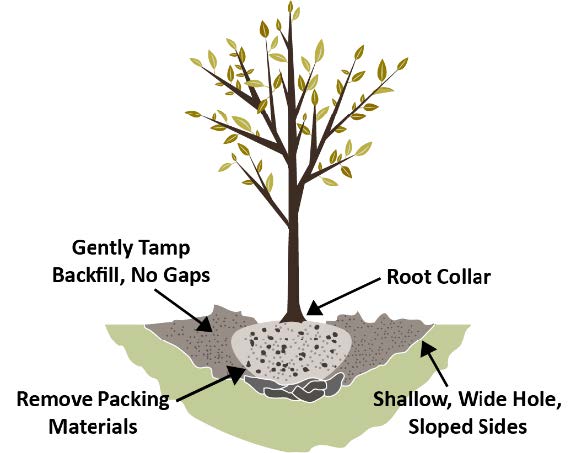

Plant trees in the early spring or fall when temperatures are mild. If trees are planted in the summer months, give careful attention to irrigation to minimize tree stress. Planting holes should be dug to accommodate the size of the root ball, with the hole 2 or 3 times wider than the width of the ball (Figure 5). Gently place trees in the hole to avoid disturbing the roots and trunk. The planting depth should place the tree so that the flare of the root collar is exposed and planted at or above ground level. Trees planted too deep may struggle to survive due to a lack of oxygen in the root zone. These trees may also produce suckers at the base more readily. Once the tree is at the right depth, backfill the hole with soil and immediately water the tree.

Irrigation

Water newly planted trees regularly to support root growth and the canopy of leaves. While trees become established, apply water to wet the soil to a 12-inch depth. It is also important to allow the soil profile time to dry out between watering to prevent root rot. Watering frequency may need to be adjusted based on the soil texture. Sandy and loamy soils may require water every 2 to 4 days, where heavy clay soils need to be watered less frequently. Oak trees require a minimal to moderate amount of water once established (1.5 to 2.0 inches of water every other week once established). Planting oaks in the turf can lead to problems associated with excessive water, such as root rot, iron chlorosis, and other diseases.

Weed Control

Weeds and turf under the tree canopy can compete with the tree for water and nutrients. String trimmers and lawn mowers being used around the trunk of the tree can also increase incidence of physical damage to the tree. Remove turf 2 to 4 feet from the trunk circumferentially to eliminate this problem. Avoid tilling under canopies as a method of weed control. This can damage roots near the soil surface and increase the incidence of soilborne diseases. A thin layer (1 to 2 inches) of mulch can be applied around the base of the tree to suppress weed growth. Ideal methods of weed control include hand pulling, hoeing, or shallow hand cultivation. Apply herbicides cautiously and take care to ensure the chemical is not applied to the tree or any associated suckers. Some broadleaf herbicides commonly used in lawns have soil activity and can be taken up by trees, leading to root damage. Oaks are especially susceptible to herbicides containing dicamba.

Fertilization

Trees do not typically need additions of fertilizers. If trees appear to be struggling, leaves are small, and growth is less than 4 to 5 inches per year, conduct a soil test to determine if additional nutrition is needed.

Pruning

Oak generally requires minimal pruning after the general structure has been established during the early years of the tree’s life. Pruning should occur in the early spring, when trees are still dormant, to make visualization of the canopy easier. Remove dead, diseased, or crossing branches from the canopy.

Disease and Pests

Powdery mildew: A common fungal disease in many landscape plants, powdery mildew derives its name from its dusty, white appearance on the surface of the plant’s leaves.

Anthracnose: Another fungal leaf disease that can affect certain tree species, including oak, during cool, wet springs, anthracnose causes brown, water-soaked lesions along the veins of the leaves (Figure 6). Disease susceptibility is highly dependent on cultivar selection.

Iron chlorosis: Iron chlorosis is a potential problem for oak. Naturally high alkaline soils (pH >7) can change the form of minerals, such as iron, making it difficult for plants to uptake mineral nutrition from the soil. Symptoms of iron deficiency include yellowing of leaf tissue between green veins, which is called interveinal chlorosis. In severe cases, the entire leaf will turn yellow, and the leaf margin will become necrotic or burned. Saturated soil conditions and compacted soil exacerbate iron chlorosis. Several methods are available for treating iron deficiency, including foliar application, soil application, and trunk injection of iron. Planting a cultivar that tolerates alkaline soil will provide you with a healthy tree that does not require amendment. For more detailed information on treating iron chlorosis, see the Control of Iron Chlorosis in Ornamental and Crop Plants fact sheet.

Common pests include scale, leaf miners, gall-forming wasps, borers, caterpillars, and nut weevils. Guidelines for homeowners are available from your local Extension agent. Additionally, you can sign up for landscape plant pest advisories from the USU Pest Advisories website at https://pestadvisories.usu.edu/.

Table 1

Common Species and Cultivars of Oak for Utah Landscapes

| Species | Cultivar | Autumn leaf color | Mature height | Mature width | Canopy shape | Hardiness zone | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bur oak | Y, B | 55' | 45' | Oval | 3 | ||

| 'Cobblestone' | Y | 55' | 45' | Oval | 3 | ||

| 'Urban Pinnacle' | Y | 55' | 25' | Pyramidal | 3 | ||

| Chinkapin oak | Y, B | 45' | 45' | Rounded | 5 | ||

| English oak | Y, B | 50' | 40' | Rounded | 5 | ||

| 'Skyrocket' | Y, B | 45' | 15' | Columar | 5 | ||

| Gambel oak | Y, O, B | 25' | 25' | Rounded | 5 | ||

| Red oak | R | 50' | 45' | Rounded | 4 | ||

| Sonoran scrub oak | G | 15' | 15' | Rounded | 7 | ||

| Shingle oak | Y, O | 50' | 40' | Oval | 5 | ||

| Shumard oak | R | 50' | 50' | Rounded | 5 | ||

| Sawtooth oak | Y | 40' | 40' | Rounded | 5 | ||

| Turkey oak | B | 45' | 50' | Rounded | 6 | ||

| 'Argenteovariegata' | B | 50' | 50' | Rounded | 6 | ||

| 'Gobbler' | Y, B | 40' | 40' | Rounded | 5 | ||

| Swamp white oak | Y, B | 45' | 45' | Rounded | 4 | ||

| 'American Dream' | Y, B | 50' | 40' | Oval | 4 | ||

| 'Bonnie and Mike' | Y | 40' | 15' | Columar | 4 | ||

| Texas red oak | Texas red oak | R | 40' | 40' | Rounded | 6 | |

| White oak | R, P | 45' | 45' | Rounded | 4 | ||

| Hybrid oaks | 'Heritage' | Y | 50' | 40' | Oval | 4 | English x bur oak |

| 'Crimson Spire' | R | 45' | 15' | Columar | 4 | English x white oak | |

| 'Praire Stature' | R, P | 50' | 40' | Pyramidal | 3 | English x white oak | |

| 'Skinny Genes' | Y | 45' | 10' | Columar | 4 | English x white oak | |

| 'Streetspire' | R | 45' | 14' | Columar | 4 | English x white oak | |

| 'Kindred Spirit' | Y, B | 30' | 6' | Columar | 4 | English x swamp white oak | |

| 'Regal Prince' | Y | 45' | 18' | Columar | 4 | English x swamp white oak |

Color key: R = red, O = orange, Y = yellow, G = green, B = brown, P = purple

* It is recommended that you check the hardiness zone for your zip code and carefully consider selections based on this information.

Note. The mature height and width listed is an average. Trees planted in the Intermountain West may have a slightly smaller final size due to limited resources.

References

- Dirr, M. A. (2009). Manual of woody landscape trees: Their identification, ornamental characteristics, culture, propagation and uses. Champaign, Ill: Stripes Pub.

- Koenig, R., & Kuhns, M. (2010). Control of iron chlorosis in ornamental and crop plants [Fact sheet]. Utah State University Extension. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1884&context=extension_curall

- Kuhns, M. (n.d.). Oaks for Utah. Utah State University Forestry Extension. https://forestry.usu.edu/trees-cities-towns/tree-selection/oaks-for-utah

Published July 2022

Utah State University Extension

Peer-reviewed fact sheet

Authors

Sheriden Hansen, JayDee Gunnell, Andra Emmertson

Related Research