Making Lifestyle Choices to Reduce Late-Life Depression Risk

Overview

Life is full of challenges and most of us will experience occasional periods of sadness. However, prolonged sadness coupled with other symptoms such as difficulty concentrating, feelings of guilt, loss of interest in things that used to produce pleasure, that negatively impact quality of life, may be a sign of depression. If a person experiences a large number of depressive symptoms that greatly impact ability to carry out daily activities, they should also seek medical help. If thoughts of suicide are experienced, medical help should be obtained immediately.

Unfortunately, negative “stigma” exists toward depression and other mental illnesses, and this can make a person with depression reluctant to seek help. If someone you care about has depression, be aware that there is much you can do to help end stigma toward those who have depression (National Alliance on Mental Illness, 2017). Educate yourself and others about mental health, and avoid the temptation to think of the individual as somehow “weak” of character or “not trying hard enough.” Focus on the person as a human being who deserves compassion and help, rather than focusing on the illness. We should encourage equality in how people perceive physical illness and mental illness.

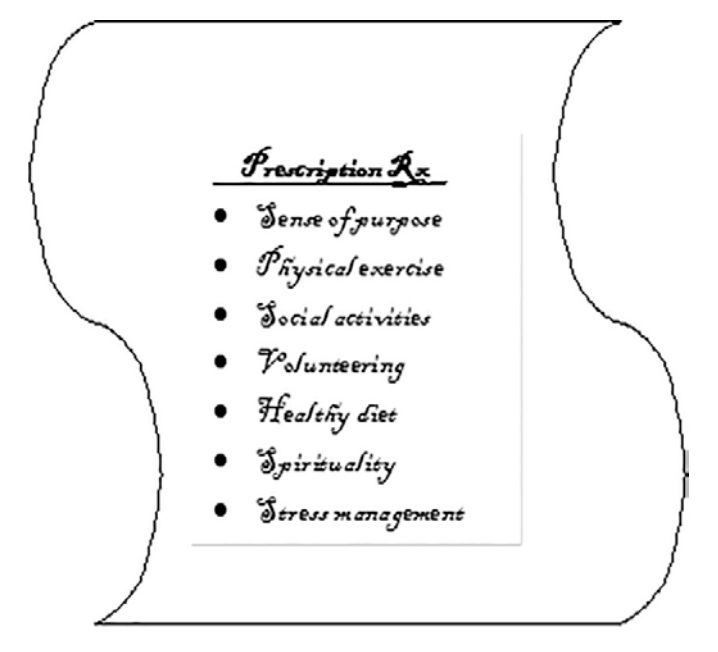

There are multiple treatment options for depression, including prescription medication and counseling therapy, which help the person learn new ways of coping with the stress that either caused the depression or made it worse. Research has also identified lifestyle factors that are related to depression. These healthy behaviors have been found to improve people’s recovery from a depressive episode, and prevent new or reoccurring depressive episodes. Most of the information in this fact sheet pertains to the benefits of healthy lifestyle practices that benefit people throughout adulthood, with several subsections devoted to scientific evidence and recommendations specific to older adults.

Being socially connected

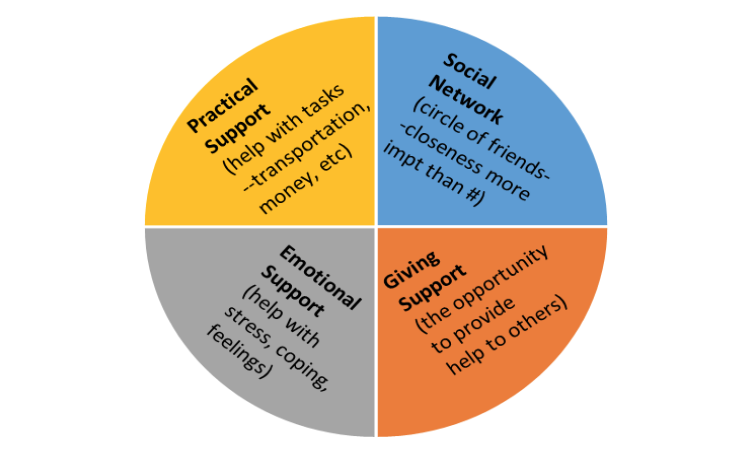

One important lifestyle practice that can help protect against depression at any age is being socially involved with others. Here are a few terms to keep in mind:

- Social network: the people in your circle of friends who you can call upon for help or social activities

- Practical support: receiving help from others such as them bringing in meals to you after surgery, driving you around for shopping or appointments when you are unable to drive, helping you move, etc.

- Emotional support: receiving help from others where they are a good listener, where they help you to feel better emotionally, showing they care about you and what you are going through.

- Giving support: giving practical and/or emotional support to others

Having a large number of people in your network is not necessary, in fact, just having one or two people in whom you can confide and trust may be all you need. Rather than size of your social network, it is the closeness you feel and the satisfaction with this group of people in your life that really matters (Fuller-Iglesias et al., 2015). Linked to lower depression rates is the sense that people in your social support network are there for you, not only for socializing in good times, but also in times of trouble. Both receiving and giving of assistance (both practical and emotional support) between people help to strengthen the relationship. Having such support when you need it, and being the person who provides it to others (particularly if giving such support is perceived as rewarding), are both important ways to reduce depression risk (Bangerter et al., 2015). In addition to the observation that good social supports help lower the risk of developing depression, a lack of social support has been linked to risk for depression becoming chronic. Among people with major depression, perceptions of low social support, particularly from family members, were highly predictive of the depression becoming more chronic or long-term (Gladstone et al., 2007). Working to improve your communication skills and ability to listen with compassion and empathy will go a long way toward helping yourself and others avoid depression.

Older adults. As we age and lose some of our professional connections and physical abilities, these changes can sometimes lead to feeling less needed or relevant. This makes spending enjoyable time interacting with friends or family on a regular basis an important way to counteract such feelings. As older adults continue to age, their social network may further decrease to include only family and a few very close friends. However, this is not unusual at all and (provided there are no signs of depression accompanying it) is a normal part of the aging process. When time remaining in life is perceived as more limited, we want to spend the time we have left where it is most important (Lockenhoff & Carstensen, 2004).

Additionally, many older adults derive a great sense of purpose, belonging and feeling needed and relevant through involvement in volunteer service activities, and consequently experience lower rates of depression (Musick & Wilson, 2003; MorrowHowell et al., 2003). It has even been demonstrated that bereaved individuals who engaged in volunteering activities to help others, experience a shorter course of depression than those who do not volunteer (Brown et al., 2008).

Physical activity

Incorporating regular physical activity into your lifestyle helps to improve the function of chemicals in the brain, including those that regulate mood (Wipfli et al., 2011; Melancon et al., 2012). A review of 11 studies found that sedentary behaviors such as TV watching or computer use are associated with an increased risk of depression (Teychenne et al., 2010). In contrast, other studies, such as one including over 9,000 people, found that regular physical activity was linked to much lower rates of depression at follow-up (Azevedo Da Silva et al., 2012). In studies testing the effectiveness of depression treatment programs, exercise has shown similar benefits to antidepressant medications (Carek et al., 2011) and cognitive-behavioral therapy (Rimer et al., 2012) as a first-line treatment for mild to moderate depression. Though more long-term studies are needed, such positive findings are encouraging and suggest that adding some exercise to one’s daily routine may not only help to keep your heart healthy and your waistline a healthier size, but may also reduce depression symptoms and depression vulnerability overall.

Older adults. Among generally healthy older adults without limiting health conditions, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention recommends comparable physical activity as for younger adults (https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/older_ adults/index.htm). This includes muscle-strengthening activities on two or more days a week that work all major muscle groups (legs, hips, back, abdomen, chest, shoulders, and arms). Additionally, it is recommended that older adults have aerobic exercise including one of the following:

- 150+ min/week of “moderate intensity” or

- 75+ min/week of “vigorous intensity” or

- An equivalent mix of moderate and vigorous activity

Older adults with a health condition that limits activity should consult with their doctor to determine a physical activity plan that is safe. In fact, if you have been leading a sedentary life, regardless of your age, it is important to check with your doctor before beginning a new exercise plan, to get help in choosing activities appropriate to your current health status and goals.

Healthy diet

The foods we eat can also impact our risk for developing depression. When thinking of healthier eating habits, it is better to focus on diet as a whole, rather than on isolated nutrients (Sanchez-Villegas, 2013). Eating foods higher in fats that have antiinflammatory properties, such as those found in fish such as salmon or olive oil, has been shown to lower one’s risk of developing depression (SánchezVillegas et al., 2007). Conversely, higher consumption of sweets (Jeffery et al., 2009) and foods rich in trans fatty acids such as fast food or commercial bakery products, have been reported as contributors to higher depression risk (SánchezVillegas et al., 2012).

Older adults. The same principles hold true for older adults in that the overall healthier eating pattern is also linked to lower depression risk. A healthier diet emphasizing fruits and vegetables, whole grains, lean meats and fish has been linked to 35% lower rates of depression (Jacka et al., 2011) as well as lower depression severity (Mamplekou et al., 2010) in samples of older adults. Additionally, in a recent study, older women had up to a 41% higher depression risk if their diet included more foods that trigger inflammation like sugarsweetened and diet soft drinks, refined grains, red meat and fewer foods that tend to lower inflammation like olive oil, leafy vegetables (Lucas et al., 2014).

Religious involvement/ Spiritual experiences

Another area of our lives that can affect our mood, well-being and depression risk is our spirituality. Spirituality and religion are related concepts that both concern sacred experiences. This can include not only the concept of God, but also anything in life that is extraordinary in nature (Hill & Pargament, 2003). In studies, psychologists have found a connection between spirituality/religiosity and depression. Women who attend church services more frequently (Norton et al., 2006) and women who report finding strength and comfort from religion (Wyshak, 2016) also reported lower levels of depression.

Besides the benefit for those who do not have depression, spirituality impacts individuals who are being treated for depression as well. In a longitudinal study, individuals taking depression medication were asked whether they believed in God (Peselow, Pi, Lopez, Besada, & IsHak, 2014). The believers had lower levels of depression after 8 weeks of treatment and they were less likely to relapse 6 months later. The researchers concluded that spirituality may offer people hope, adaptation, and beliefs that circumstances are not meaningless, which may help them recover from depression more effectively

Not smoking/quitting smoking and avoiding heavy alcohol use

Those who smoke (Vermeulen-Smit, Ten Have, Van Laar, & De Graaf, 2015) and those who are heavy drinkers (An & Xiang, 2015) are at an increased risk for later developing depression. The converse has also been found, that individuals who have depression are more likely than non-depressed persons to subsequently become smokers or heavy drinkers (An & Xiang, 2015). One hypothesis as to why smoking and heavy alcohol consumption often co-occur is that people may use these products as a form of self-medication to cope with stress (Little, 2000). It has also been shown that smokers who have depression tend to have high dependence on nicotine (found in tobacco). They also more often suffer from more severe negative moods, and they are at higher risk for their depression getting worse after quitting smoking (Cosci et al., 2011). The underlining biological mechanism explaining the interrelationships between smoking, heavy drinking and depression are not well understood and more studies are needed. However, if a non-depressed person is thinking about quitting smoking, lowering depression risk can add to other health reasons to help motivate them to quit.

Learning to manage your stress

In life, there are times we may have stressful experiences that are short and intense, or others that are more long-term, both of which are risk factors for depression and its persistence (Paykel, 2003). The good news is that there are effective coping styles that can be learned to help combat the negative thoughts and feelings and increase protection from depression. These include such practices as meditation and mindfulness where you slow down and take time to be aware of the positive aspects in the moment (Riemann et al., 2016). Another approach is to consciously choose to manage your reaction to stress and not allow yourself to get angry or stressed out, but instead to consider how you can gain from learning and growing through your adversities (DeGraff & Schaffer, 2008). Additionally, there is a benefit of reminding oneself of the high quality relationships in life, a form of “benefit reminding” (whether just thinking or even journaling about such awareness), and this is linked to higher levels of mental wellbeing (Brand et al., 1995).

Older adults. Older adults are certainly not immune from experiencing stress; indeed, they may have many significant life changes that can be stressful. Interestingly, however, some research on older people suggests that they are even better than younger people at managing their emotions with the kinds of strategies described above (Carstensen, 2006; Scheibe & Blanchard-Fields, 2009).

Higher depression protection when you do more than one of the above

While many of our life experiences are uncontrollable, taking part in multiple positive health behaviors can give you greater protection from depression. In one study, healthy diet, physical activity, and smoking status were used to compute a score for healthy lifestyle. Those with the highest score were 96% less likely to be depressed (Saneei et al., 2016). Another study reported that people who participated in one, two or three healthy behaviors were 15%, 67% and 87% respectively, less likely to have depression than people with no healthy behaviors (Loprinzi & Mahoney, 2014). For each additional behavior, the protection was even higher. This means that those who do not feel like they can participate in all the healthy lifestyle behaviors, do not need to be completely discouraged. Even participating in just a few or even just one of these behaviors can decrease your likelihood of becoming depressed.

The “whole you”—holistic approach

There are several locations throughout the world where people have a much higher likelihood of living beyond 100 years. These areas also have very low rates of depression (Beuttner, 2010). In addition to other good lifestyle practices, like being part of a strong social network and eating healthy diets, these long-lived people make physical activity a natural part of their everyday lives by walking or biking everywhere, gardening, shopping, visiting others, and so on (no need for a gym or personal trainer). These healthy lifestyle practices discussed in this report don’t operate independently. They can all work together toward building a healthy lifestyle (with benefits like living longer), and can be quite complementary and even overlapping. Think about ways you can combine healthy behaviors into a single task – for example instead of working on improved social engagement and exercise as separate tasks, consider taking a daily walk with a friend to benefit you from both the exercise and the social interaction!

Summary

Depression is a complex condition involving insufficient levels of brain chemicals, life stressors, thought processes, behaviors, and coping mechanisms. Medications and counseling therapy are effective in treating depression, and research suggests that several lifestyle practices also help to protect us from depression, and speed up our recovery if we do experience it. These behaviors, such as being socially connected, eating healthy and exercising, cost little to nothing but can have profound benefits on our overall quality of life and help us to stay depression-free.

References

- An, R., & Xiang, X. (2015). Smoking, heaving drinking, and depression among U.S. middle-aged and older adults. Preventive Medicine, 81, 295-302. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.09.026

- Azevedo Da Silva, M., Singh-Manoux, A., Brunner, E. J., Kaffashian, S., Shipley, M. J., Kivim aki, M., & Nabi, H. (2012). Bidirectional association between physical activity and symptoms of anxiety and depression: the Whitehall II study. European Journal of Epidemiology, 27, 537–546.

- Bangerter, L., Kim, K. Zarit, S. Birditt, K., & Fingerman, K. (2015). Perceptions of giving support and depressive symptoms in late life. Gerontologist, 55(5), 770-779.

- Buettner, D. (2010). Thrive. Finding Happiness the Blue Zones Way. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society.

- Brand, E. F., Lakey, B., & Berman, S. (1995). A preventive, psychoeducational approach to increase perceived social support. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(1), 117-135.

- Brown, S., Brown, R., House, J. & Smith, D. (2008). Coping with spousal loss: potential buffering effects of self-reported helping behavior. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(6), 849-861.

- Carek, P. J., Laibstain, S. E., Carek, S. M. (2011). Exercise for the treatment of depression and anxiety. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 41, 15–28.

- Carstensen, L. L. (2006). The influence of a sense of time on human development. Science, 312, 1913- 1915.

- Cosci, F., Pistelli, F., Lazzarini, N., & Carrozzi, L. (2011). Nicotine dependence and psychological distress: outcomes and clinical implications in smoking cessation. Psychological Research & Behavior Management, 4, 119–128.

- Fuller-Iglesias, H. (2015). Social ties and psychological well-being in late life: the mediating role of relationship satisfaction. Aging & Mental Health 19(12), 1103-1112.

- Gladstone, G. L., Parker, G. B., Malhi, G. S., & Wilhelm, K. A. (2007). Feeling unsupported? An investigation of depressed patients' perceptions. Journal of Affective Disorders, 103(1-3), 147-54.

- Jacka, F. N., Mykletun, A., Berk, M., Bjelland, I., & Tell, G. S. (2011). The association between habitual diet quality and the common mental disorders in community-dwelling adults: the Hordaland Health study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 73(6), 483-490. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318222831a.

- Jeffery, R. W., Linde, J. A., Simon, G. E., Ludman, E. J., Rohde, P., Ichikawa, L. E., & Finch, E. A. (2009). Reported food choices in older women in relation to body mass index and depressive symptoms. Appetite, 52, 238–240.

- Little, H. J. (2000). Behavioral mechanisms underlying the link between smoking and drinking. Alcohol Research and Health, 24 (4), 215–224.

- Lockenhoff, C. E., & Carstensen, L. L. (2004). Socioemotional selectivity theory, aging, and health: the increasingly delicate balance between regulating emotions and making tough choices. Journal of Personality, 72(6), 1395-1424.

- Loprinzi, P. D., & Machoney, S. (2014). Concurrent occurrence of multiple positive lifestyle behaviors and depression among adults in the United States. Journal of Affective Disorders, 165, 126-130. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.073

- Lucas, M., Chocano-Bedoya, P., Schulze, M. B. Mirzaei, F., O’Reilly, E. J. …Ascherio, A. (2014). Inflammatory dietary pattern and risk of depression among women. Brain Behavior and Immunity, 36, 46–53.

- Mamplekou, E., Bountziouka, V., Psaltopoulou, T., Zeimbekis, A., Tsakoundakis, N., Papaerakleous, N. … Panagiotakos, D. (2010). Urban environment, physical inactivity and unhealthy dietary habits correlate to depression among elderly living in eastern Mediterranean islands: the MEDIS (MEDiterranean ISlands Elderly) study. Journal of Nutrition Health and Aging, 14, 449–455.

- Melancon, M. O., Lorrain, D., & Dionne, I. J. (2012). Exercise increases tryptophan availability to the brain in older men age 57–70 years. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 44, 881–887.

- Morrow-Howell , N. , Hinterlong , J. , Rozario , P. A., & Tang , F. (2003). Effects of volunteering on the well-being of older adults. Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 58, S137 – S145 .

- Musick , M. A., & Wilson , J. (2003). Volunteering and depression: The role of psychological and social resources in different age groups. Social Science & Medicine, 56, 259 – 269.

- National Alliance on Mental Illness (2017). Nine ways to fight mental health stigma. Retrieved on February 19, 2017 from http://www.nami.org/Blogs/NAMI-Blog/October2015/9-Ways-to-Fight-Mental-Health-Stigma

- Norton, M. C., Skoog, I., Franklin, L. M., Corcoran, C., Tschanz, J. T., Zandi, P. P., …Steffens, D.C. (2006). Gender differences in the association between religious involvement and depression: The Cache County (Utah) Study. Journals of Gerontology B: Psychological Sciences, 61, 29-136.

- Hill, P. C., & Pargament, K. I. (2008). Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of religion and spirituality: Implications for physical and mental health research. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, S(1), 3-17. doi: 10.1037/1941- 1022.S.1.3

- Paykel, E. S. (2003). Life events and affective disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 108, 61−66.

- Peselow, E., Pi, S., Lopez, E., Besada, A., & IsHak, W. W. (2014). The impact of spirituality before and after treatment of major depressive disorder. Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience, 11(3-4). 17- 23.

- Riemann, D. Hertenstein, E., & Schramm, E. (2016). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. The Lancet, 387(10023), 1054.

- Rimer, J., Dwan, K., Lawlor, D. A., Greig, C. A., McMurdo, M., Morley, W., & Mead, G. E. (2012). Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 7, CD004366.

- Sánchez-Villegas, A. & Martinez-González, M. A. (2013). Diet, a new target to prevent depression? BMC Medicine, 11(3). doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11- 3.

- Sánchez-Villegas, A., Toledo, E., de Irala, J., RuizCanela, M., Pla-Vidal, J., & Martínez-González, M. A. (2012). Fast-food and commercial baked goods consumption and the risk of depression. Public Health Nutrition, 15, 424-432.

- Sánchez –Villegas, A., Henríquez, P., Figueiras, A., Ortuño, F., Lahortiga, F., & Martínez-González, M. A. (2007). Long chain omega-3 fatty acids intake, fish consumption and mental disorders in the SUN cohort study. European Journal of Nutrition, 46, 337-346.

- Saneei, P., Esmaillzadeh, A., Keshteli, A. H., Roohafza, H. R. Afshar, H., Feizi, A., & Adibi, P. (2016). Combined healthy lifestyle is inversely associated with psychological disorders among adults. Plos ONE, 11(1), 1-14.

- Scheibe, S. & Blanchard-Fields, F. (2009). Effects of regulating emotions on cognitive performance: What is costly for young adults is not so costly for older adults. Psychology and Aging, 24, 217-223.

- Teychenne, M., Ball, K., & Salmon, J. (2010). Sedentary behavior and depression among adults: a review. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 17, 246–254.

- Vermeulen-Smit, E., Ten Have, M., Van Laar, M., & De Graaf, R. (2015). Clustering of health risk behaviours and the relationship with mental disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 171, 111- 119. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.09.031

- Wyshak, G. (2016). Income and subjective well-being: New insights from relatively healthy American women, ages 49-79. Plos ONE, 11(2).

- Wipfli, B., Landers, D., Nagoshi, C., & Ringenbach, S. (2011). An examination of serotonin and psychological variables in the relationship between exercise and mental health. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, 21, 474–481.

Authors

Maria C. Norton; Elizabeth B. Fauth; Jessica Weyerman

Related Research