Turfgrass Cultural Practices and Insect Pest Management

September 2010

Diane G. Alston, Entomologist (No longer at USU) • Kelly Kopp, Turfgrass Specialist

Do You Know?

- Good cultural practices and prevention of stress are critical to keeping turfgrass healthy and pestfree.

- Good turfgrass management is dependent on optimal timing of cultural and pest control treatments.

- There are four main insect pest groups that attack turfgrass in Utah.

There are a number of insects that can cause aesthetic and economic loss to turfgrass in Utah – in home lawns as well as in athletic fields and on recreational lands. Good turfgrass cultural practices are the primary way to prevent insect infestation and turfgrass damage.

Cultural Practices to Prevent Turf Insect Problems

Refer to Fig. 1 for optimal timing of turfgrass cultural practices.

Mowing

As a rule, regular grass mowing height should be 2 to 3½ in. to promote root growth and stress tolerance of turfgrasses. Mow regularly to avoid removing more than one third of the desired leaf length at any one time. Clippings should be recycled back into the lawn as a source of nutrients and organic matter. Consider raking turfgrass areas to remove residual clippings and encourage upright growth of the leaves after a long winter under snow cover.

Fertilization

Nitrogen is of primary concern in turfgrass fertilization. In the early spring, apply 1 pound of slow-release nitrogen fertilizer per 1000 ft2 of lawn area. This will help the grass recover from winter stress and damage. It will also be especially helpful for areas that have suffered damage due to diseases such as pink and gray snow mold. In a slow-release form, nitrogen fertilizer will provide a consistent source of nutrients as the growing season begins. Apply a second pound of slow-release nitrogen fertilizer per 1000 ft2 of lawn area in late spring to early summer. This will allow the grass to enter into the warmest months of the year with energy reserves. Finally, apply 1 pound of quick-release nitrogen fertilizer per 1000 ft2 of lawn area after the last mowing of the year. The grass should still be green, but should have stopped actively growing. The grass will still have the capacity to take up nitrogen, but it will store the nutrient as energy until the following spring. The last fertilization is particularly important because of the drought tolerance that it imparts to the grass during the following growing season.

Aeration

Spring is an ideal time to aerate your lawn if the soil is compacted or there is a significant layer of thatch beneath the grass. If the thatch layer is more than ½ in. thick, consider core aeration to stimulate the natural decomposition process. Likewise, in a fine-textured soil compaction may occur, particularly in high traffic areas. Core aeration will help to alleviate this compaction. In particularly compacted areas, a second core aeration in the fall may be warranted.

Irrigation

In the spring, delay watering as long as possible to encourage deep rooting of turfgrasses prior to the start of the irrigation season. Irrigation over the growing season should be applied to replace water taken up by the grass and lost to evaporation, but not in excess of this amount. Water-stressed grasses may be more susceptible to insect pressure; however, over-watered grasses may be more susceptible to diseases. In general, less irrigation will be required in the spring and fall, while more will be required during the heat of the summer. Specific irrigation schedules for different areas of the state may be obtained from your local USU County Extension office.

Seeding & Overseeding

Fall is the ideal time to seed new turfgrass areas or to overseed areas that may have been damaged during the growing season by insect pests or diseases. The cooler temperatures will promote germination and growth of cool season turf species such as Kentucky bluegrass, tall and fine fescues, and perennial ryegrass. Choose pest-resistant and turfgrass cultivars recommended for your location. For more information: http://extension.usu.edu/files/publications/publication/HG_Grass_2004_01.pdf

Turfgrass Insect Pests

White Grubs

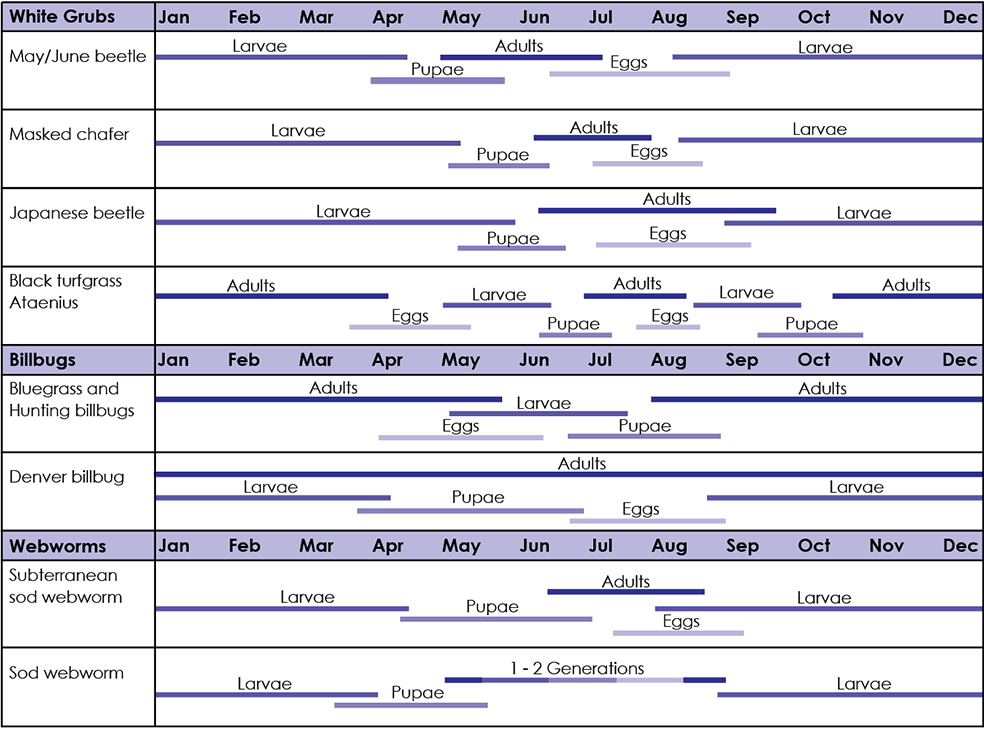

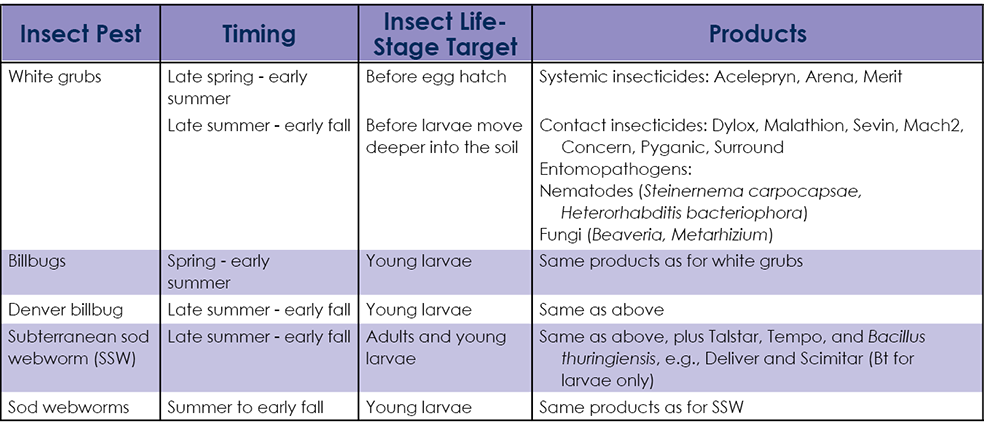

White grubs are the immature stage of scarab beetles (Fig. 2), and primarily feed on turfgrass roots. The May/June beetle (Fig. 3), masked chafer, and black turfgrass Ataenius are established in Utah. The Japanese beetle was introduced into the Orem area in 2006, but an eradication program has currently minimized its population. Brown patches in grass from grub feeding injury often aren’t apparent until late summer in an otherwise healthy turf. Heavily damaged turfgrass can feel spongy, pull up easily, and tear away from the roots that have been chewed off. When full-grown, white grubs range in length from 3/8 to 2 in. and form a C-shape when at rest. Grubs bear three obvious pairs of legs near their head end. The life cycle of different white grub species varies from one to several generations per year (Fig. 8). Economic thresholds for white grubs vary with species due to body size and feeding intensity: 3-5 per ft2 for May/June beetle, 8-10 per ft2 for masked chafer, and 30-50 per ft2 for black turfgrass ataenius. Turf/soil sampling is most effective with a golf cup-cutter or by cutting 6 in. × 6 in. squares on three sides with a hand trowel. Carefully examine the root zone and estimate the number of grubs per ft2. Biological control by natural predators and supplementation of pathogens, such as beneficial nematodes and fungi, can help maintain grub populations below economic thresholds; however, when damage is detected, control with insecticides is often necessary. Table 1 provides a listing of control products and optimal timing to target susceptible life stages. It is critical to reduce the thatch layer to no more than 1/2 in. deep and/or to aerate the soil to enhance chemical penetration, and to apply 1/2 to 3/4 in. of water after application to move insecticides into the root zone. Repeat irrigation every 4-5 days to continue chemical movement into the soil. Long-lasting clean-up of white grubs often requires several years of treatment. For more information: http://extension.usu.edu/files/publications/factsheet/white-grub07.pdf

Billbugs

Three or four species of billbugs occur in Utah. In the northern region, the Denver (Fig. 4) and bluegrass billbugs are common, and infest cool-season grasses. The Phoenix and hunting billbugs infest warm-season grasses, such as bermudagrass and zoysiagrass. The Phoenix billbug has been identified in the Moab area and the hunting billbug may occur in lower elevation areas of southwestern Utah. Billbugs are snout beetles or weevils.

In contrast to white grubs, billbug larvae are smaller (up to only 1/2 in. long) and legless (Fig. 5). They have white bodies with a brown head, and resemble grains of puffed rice. Billbug larvae feed in the crown and upper root zone and damage is typically apparent in early and mid summer. Early detection is important to good control because young larvae present in the spring are easier to kill than older larvae (Fig. 8). Turfgrass looks stressed with small brown patches (Fig. 6). Grass blades can be easily pulled away from the crown in small tufts. Sawdustlike frass (insect poop) is often evident in the thatch. The treatment threshold is 1 larva per ft2. See Table 1 for products and optimal application timing. For more information: http://extension.usu.edu/files/publications/ factsheet/billbug07.pdf

Subterranean Sod Webworm

The subterranean sod webworm (SSW) is a moth/ caterpillar insect that feeds in turfgrass crowns and roots. SSW injury looks similar to that of white grubs. Damage begins as small brown patches that can increase rapidly in the late summer to early fall. This insect has become a persistent turfgrass pest along the Wasatch Front, and has been more difficult to control than billbugs and the common sod webworm. SSW larvae are dirty-white to grey in color with an orangebrown head. Mature larvae reach 3/4 in. long. Adults are cream to gray moths (1/2 in. long) with tan and brown stripes (Fig. 7). Moths fly just above the turfgrass at dusk/ night, and are active in summer (Fig. 8). The treatment threshold is only 1-2 larvae per ft2. Otherwise healthy turfgrass can tolerate low infestations, and can recover if properly managed (see discussion of good cultural practices above). Turf/soil samples as described for white grubs are required to identify larvae feeding in the crown and root zone. See Table 1 for insecticide control information. For more information: http://extension.usu.edu/files/publications/factsheet/cranberry-girdlers07.pdf

Sod Webworms

The common sod webworm is a complex of grass-infesting species of snout moths/caterpillars. At least seven species occur in Utah. The different species look similar: adults are dull brown and gray moths (3/4 to 1 in. wingspan) and larvae are brown-grey to green with dark circular spots and hairs on their sides (5/8 to 1 in. long)(Fig. 9). Larvae spend the winter in cocoons in the thatch layer and begin to feed in the spring with warming temperatures (Fig. 8). Larvae feed on grass blades at night and retreat to the thatch during the day. Feeding damage begins as general turf thinning, but can intensify into small brown patches. Injury is evident during the summer and into the early fall. Sod webworm feeding is above ground and roots remain intact, unlike with the SSW. Small green-brown pellets of caterpillar frass can be seen in the thatch. To sample, larvae can be flushed from the thatch by pouring soapy water (1 Tbsp liquid dishwashing detergent in 1 gallon of water) into the turf. The treatment threshold and control options are the same as for SSW. See Table 1 for effective products and recommended timing. For more information: http://extension.usu.edu/files/publications/factsheet/sod-webworm07.pdf

Additional Reading

- Ali, A. D., and C. L. Elmore. Turfgrass pests (121 pp.). University of California Cooperative Extension, Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources Publication 4053, Oakland, CA.

- Brandenburg, R. L., and M. G. Villani. Handbook of turfgrass insect pests (140 pp.). Entomological Society of America, Lanham, MD.

- Vittum, P. J., M. G. Villani, and H. Tashiro. Turfgrass insects of the United States and Canada, Second edition (422 pp.). Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY.