Spongy Moth

March 2022

Ann Mull, Extension Assistant (No longer at USU), Lori R. Spears, CAPS Coordinator (No longer at USU)

Quick Facts

- Spongy moth is the new name for European gypsy moth. Its official common name was changed to respect cultural sensitivity and references the egg case’s spongelike appearance.

- Spongy moth is among North America’s most destructive invasive forest pests. Infestations have caused significant agricultural, ecological, and economical losses.

- In the eastern U.S., this pest defoliates an average of 700,000 acres each year and causes more than $200 million in annual damages.

- Oaks (Quercus spp.) are the preferred host, but hundreds of plant species are vulnerable to attack, including hardwood and softwood trees, fruit trees, and shrubs.

- Long-distance spread is caused primarily by the movement of unsuspected infested materials.

- In Utah, spongy moth has been detected and eradicated in the past. Parts of Utah, including the Wasatch Front, have favorable conditions for this pest to establish.

Introduction

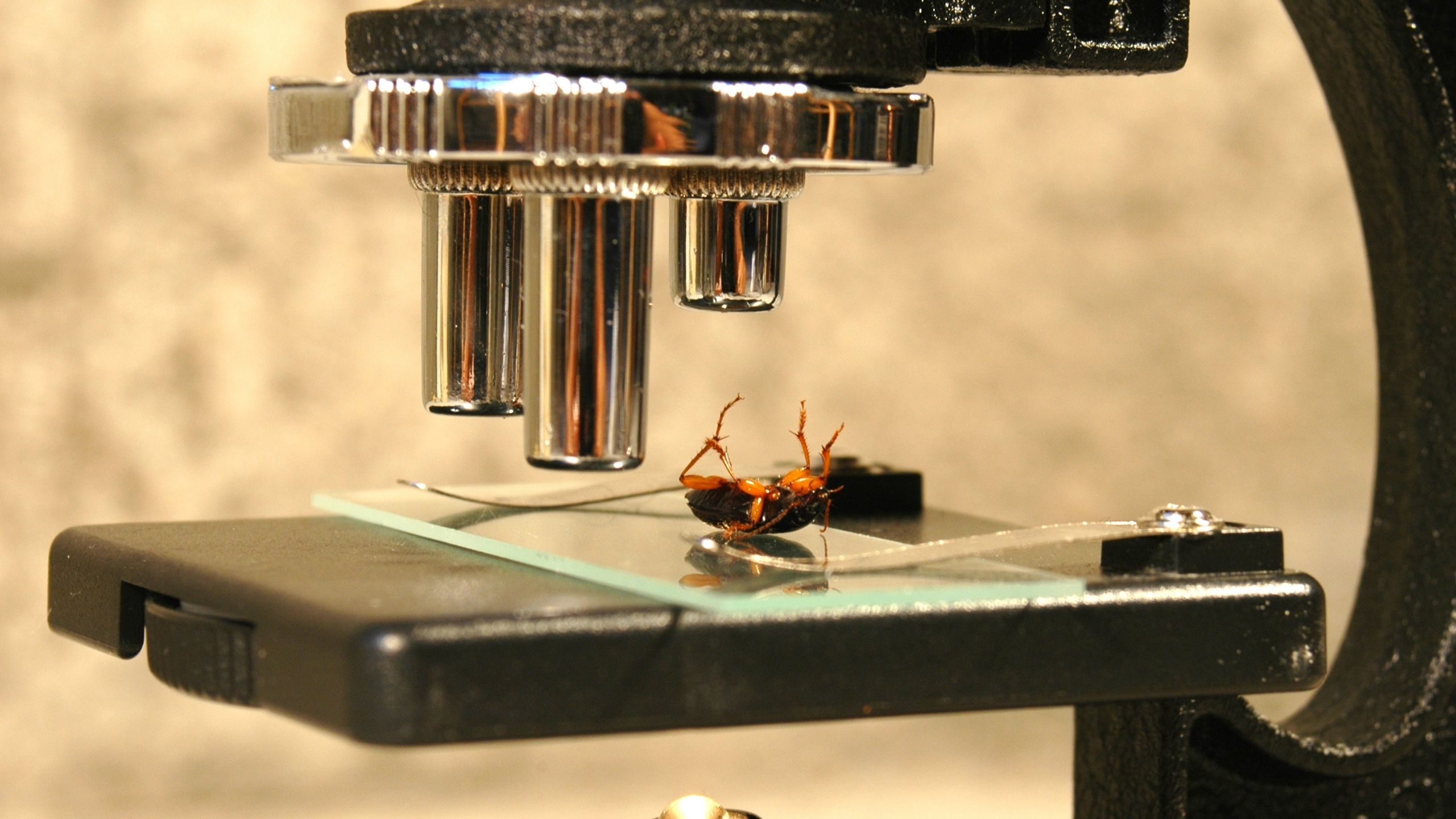

Spongy moths (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) (Fig. 1) are invasive leaf-eating (defoliating) pests that threaten trees and shrubs in urban, suburban, and rural landscapes. The spongy moth was accidentally introduced to the U.S. in 1869 by an amateur French entomologist in Massachusetts who sought to establish a hardier American silkworm industry. These moths now commonly occur in the northeastern U.S. and are also found in parts of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, North Carolina, Ohio, Virginia, West Virginia, Wisconsin, California, Oregon, and Washington.

In Utah, the spongy moth is anticipated to survive and multiply rapidly if populations become established (Utah Department of Agriculture and Food [UDAF], 2021). This pest was first detected in Utah in1988 in monitoring traps and was quickly eradicated via extensive trapping and spray applications of Bacillus thuringiensis kurstaki (Btk), a naturally occurring bacterium. Since that time, additional specimens have been detected and eradicated, most recently in 2016 (1 moth) and 2020 (1 moth). In North America, the nearly identical Asian subspecies, L. dispar asiatica, is also a concern. Lymantria dispar asiatica is not currently established in the U.S. and has not been detected in Utah, but it is thought likely to spread quickly throughout the U.S. if established. Unlike spongy moths, female L. dispar asiatica are strong fliers and are attracted to light sources, including those located in ports and shipyards. Egg masses and pupae of L. dispar asiatica have been introduced from foreign ships and cargo entering ports predominantly in western North America, and this pest was detected and eradicated on 20 or more occasions across the U.S. between 1991 and 2014, most near Utah in Oregon and Washington (Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Plant Protection and Quarantine [APHIS PPQ], 2016). DNA testing is typically necessary for identification of these two subspecies.

Long-distance spread of the spongy moth is primarily from the movement of infested materials such as firewood, fence posts, stones, lawn furniture, vehicles, and equipment. In addition to an existing federal order aimed at preventing the spread of spongy moth, the Utah Administrative Code R68-14 outlines the quarantine in place for transportable articles that may contain this pest (UDAF, 2021). If you suspect this pest in Utah, please contact UDAF or the Utah Plant Pest Diagnostic Lab.

Description

Laying an Egg Mass (bottom). Image courtesy of Karla Salp, Washington State Department of Agriculture, Bugwood.org

(top); Steven Katovich, Bugwood.org (bottom).

Awaiting Dispersal. Image courtesy of Brian Schildt, Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture, Bugwood.org.

Adults

Females (Fig. 2) have creamy-white colored wings with darker sawtooth-like markings, and the antennae are thin and threadlike (Fig. 1). Wingspans of female spongy moths are 2.5 to 3.5 inches (6 to 9 cm), while female L. dispar asiatica wingspans are 3.5 inches (9 cm) or larger. Males’ wings of both subspecies span about 1.5 inches (4 cm) and are greyish-brown to mottled brown in color with black markings (Fig. 1). Males have feather-like antennae for detecting female pheromones. Males and females of both subspecies can have an inverted V-shape marking on each wing that points to a dot.

Other Life Stages

Eggs are about 1/25 inch (1 mm) in diameter, and resemble tiny gray- or black-colored pellets. They are laid in masses up to 1.5 inches (4 cm) in length and 3/4 inch (2 cm) in width, and each mass may contain from 100 to more than 1,000 eggs. The egg mass has a hard covering that is firm to the touch and velvetlike in texture, with fuzz-like “hairs” that are blonde, brownish, or rust (Fig. 3). Old egg masses tend to feel soft and spongy.

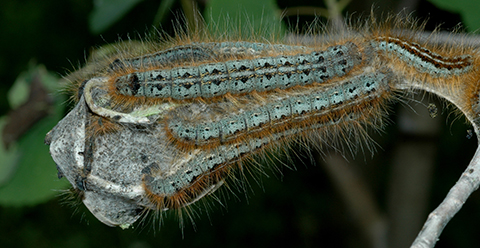

Larvae (caterpillars) (Fig. 4) have long hair-like bristles and vary in color. Newly-hatched caterpillars are black or tan, about 1/8 inch (3 mm) in length, and may have irregularly shaped yellow marks on the upper body surface. Older caterpillars have long, tan bristles, five pairs of blue spots followed by six pairs of red spots along the back, yellow spots along the sides of the body, and coloration that is typically dark gray but can range from yellow to black. Mature caterpillar lengths range from 1.5 to 3.5 inches (about 4 to 9 cm). The larvae do not produce silken tents or create extensive webbing.

Pupae (Fig. 5) are dark brown and about about 2 inches (5 cm) in length. They have a hardened teardrop-shaped shell that is covered in small “hairs.”

Plant Hosts

Larvae feed on the foliage of more than 300 tree and shrub species. Spongy moths feed primarily on deciduous trees, but L. dispar asiatica readily feed on more than 500 deciduous and some coniferous trees from over 100 plant families, including the soft, young needles of Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) (Molet, 2016; Keena & Richards, 2020), a common tree in Utah’s forests.

Preferred and susceptible hosts include oak (Quercus spp.); aspen and poplars (Populus spp.); willow (Salix spp.); apple (Malus spp.); hawthorn (Crataegus spp.); mountain ash (Sorbus spp.); larch (Larix spp.); sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua); and linden (Tilia spp.); as well as some species of alder (Alnus spp.) and birch (Betula spp.).

Lesser preferred hosts include maple (Acer spp.); juniper (Juniperus spp.); sumac (Rhus spp.); walnut (Juglans spp.); and elm (Ulmus spp.). Least preferred hosts include ash (Fraxinus spp.); dogwood (Cornus spp.); and lilac (Syringa spp.) (Coleman et al., 2020).

Life History

Spongy moths undergo complete metamorphosis, maturing from egg to larva to pupa to adult. There is one generation per year. The overwintering eggs are capable of surviving temperatures as low as -22 °F (-30 °C) without the protection of snow; under snow cover, eggs can survive colder temperatures (Ananko & Kolosov, 2021; Streifel et al., 2019). Eggs hatch in spring, coinciding with bud break, and the emerging larvae climb to the tops of trees where they dangle from silken threads (Fig. 6) and are dispersed by wind (“ballooning”). Young caterpillars eat leaves in the upper canopy during the day, rest on the foliage at night, and have a diet that is largely restricted to oak, poplar, willow, or larch. Older caterpillars have a broader diet and will typically feed at night and descend from the canopy at dawn to rest in cryptic locations, such as at the base of trees, under rocks, or in stumps, logs, or bark crevices. During outbreaks, however, they will feed during the day. The growing larvae undergo five (males) or six (females) molts (instars) over 6 to 8 weeks and are most active during May and June. Mature larvae pupate typically in June or July for 10-14 days before emerging as adult moths (Coleman et al., 2020). Spongy moths do not create or feed within silken webs or tents.

Adults are present between early June and early October, and they live from 1 to 3 weeks. Adults do not feed. Female spongy moths cannot fly, and they remain on the tree on which they pupated, releasing scents (pheromones) to attract males to mate. In contrast, adult female L. dispar asiatica are strong and active fliers and, in some cases, can fly up to 25 miles (40 km) seeking a suitable egglaying site (Agricultural Research Service [ARS], 2021). Male spongy moths are active during the day (diurnal) and have an erratic an each female lays 1 egg mass, covering the eggs with hairs (setae) plucked from her abdomen. Egg masses are laid between July and September, depending on weather and location, on outdoor surfaces such as tree trunks, branches, rock outcroppings, firewood, houses, patio furniture, trailers, and vehicles. Adults of both sexes die soon afterwards. Where it is established, this pest typically undergoes undulating cycles in which populations increase for several years, then decrease for up to 10 years, and then increase again; this is thought to result from a combination of food availability and disease prevalence (Coleman et al., 2020).

Damage Symptoms

of Forestry, Bugwood.org (bottom).

Outbreaks are more common on dry sites with poor, shallow soils and rock outcroppings. During outbreaks, larvae cause decreased plant growth and vigor, and extensive feeding from large infestations defoliates trees and shrubs, causing weakened trees that are more susceptible to disease or attack by other insects. Host mortality has been shown to increase when defoliation follows drought. Large infestations can kill large sections of landscaping, orchards, and forests (Fig. 7), and destroy watersheds. Healthy trees usually tolerate 1 to 2 years of intensive attack, but repeated infestations weaken the tree to a point where recovery is improbable. Outbreaks can also destroy critical habitat and food sources for many other organisms. In some forested areas, introductions of spongy moths have resulted in oaks being replaced by less desirable species (CABI, 2021; Wallner, 2000). In extreme infestations, their presence can lower property values, and their excrement (feces), egg masses, molted skins, pupal casings, and dead moths can be a nuisance. In sensitive individuals, the caterpillar hairs can cause allergic reactions.

Monitoring And Prevention

USDA, Bugwood.org (bottom).

In Utah, state and federal personnel monitor spongy moths with pheromone traps (Fig. 8) that attract newly emerged, nonmated males. Traps are placed in high-risk areas. Utahns should familiarize themselves with the spongy moth, keeping in mind that the caterpillars and egg masses are more observable than the adult moths.

- Look for life stages on and near your home and surroundings, and be aware of potential “hitchhikers” if you travel through an area where this pest occurs.

- Maintain tree and shrub vigor, ensuring plants are sufficiently watered during periods of drought stress, and properly prune and fertilize when necessary.

- Maintain a 4-foot diameter at the base of trees that is weedand grass-free to limit competition for resources (such as water and nutrients) and to lessen trunk damage from lawn equipment (see www.forestry.usu.edu/trees-cities-towns/ for a list of articles on tree care).

- As a general rule, keep firewood inside county boundaries, as spongy moths--like many other forest pests--can spread to new areas on infested firewood and other wood materials.

- When selecting live Christmas trees, utilize local sources or UDAF-compliant vendors, and inspect trees and other greenery for signs of hitchhikers that can include spongy moths (UDAF, 2019).

Management

Management efforts typically target the egg and caterpillar stages. As spongy moths are not currently known to be in Utah, there is no current need for control of this pest. The following content is for informational purposes.

Biological Control

Many natural enemies feed on and attack spongy moths, including various small mammals (mice, voles, shrews, and skunks), birds, invertebrates (ground beetles, ants, and spiders), viral and fungal pathogens (particularly nucleopolyhedrosis virus and Entomophaga maimaiga), and parasitoids that include parasitic wasps (e.g., Aleiodes indiscretus and Pimpla disparis) and flies (e.g., Parasetigena silvestris) (Blackburn & Hajek, 2018; CABI, 2021).

Bioinsecticides made from Bacillus thuringiensis kurstaki (Btk) can be used to control young larvae. Btk is short-lived, minimizes nontarget effects, and has low environmental impact. In larger areas with high infestations, Btk may be used with pheromone mating disruptors, including baited traps or aerial foliar sprays. Such pheromones include Disrupt II, Luretape Gypsy Moth, and Luretape Plus. Gypchek (nucleopolyhedrosis virus) is specific to this pest and approved for use in environmentally sensitive areas, but it is more costly to produce (Coleman, 2020).

Chemical Control

Insect growth regulators such as diflubenzuron and tebufenozide should be used with caution due to their effects on nontarget species. If chemical control is warranted, certain labeled broad spectrum insecticides may be applied by homeowners to the tree crown or ground to target feeding larvae; however, know that broad spectrum insecticides are nondiscriminatory and kill beneficial insects. For this reason, these have rarely been used in large-scale treatment programs since the late 1980s (Coleman, 2020). As pesticide registrations change frequently, please contact county, state, or federal pesticide coordinators for currently registered insecticide listings.

Caterpillar Look-Alikes

In Utah, common native caterpillar defoliators that may be confused with spongy moths include the western tent caterpillar (Malacosoma californicum) and the fall webworm (Hyphantria cunea). Western tent caterpillars (Fig. 9) feed on broadleaf trees and shrubs throughout the western U.S. Young larvae are about 1/8 inch (0.3 cm) long and are dark brown to black in color with white hairs. Mature larvae can be 2 inches (5 cm) in length and are highly variable in color. Most commonly they have pale blue heads and bodies, speckled black markings, a mid-dorsal stripe edged by two black or yellowish-orange bands bordered with black, and are covered with orange-brown hairs with white tips. Unlike the spongy moth, western tent caterpillars create and feed inside extensive silken tents (Davis & Jones, 2011).

The fall webworm (H. cunea) (Fig. 10) is a common defoliator moth of ornamental and fruit trees in Utah. Young larvae are pale yellow with two rows of black marks along their bodies. Full-grown larvae are about 1 inch (2.5 cm) long and have highly variable coloration, but are usually greenish with a broad, dusky stripe along the back, a yellowish stripe along the side, and have long whitish hairs that originate from black and orange bumps. The larvae feed inside silken tents (Davis & Jones, 2011).

References and Further Reading

- Ananko, G. G. & Kolosov, A. V. (2021). Asian gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar L.) populations: Tolerance of eggs to extreme winter temperatures. Journal of Thermal Biology 102, 103123.

- Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Plant Protection and Quarantine (APHIS PPQ). (2016). Pest alert: Asian gypsy moth [APHIS 81-35- 027]. U.S. Department of Agriculture.

- Agricultural Research Service (ARS). (2021). Gypsy moth. Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture.

- Blackburn, L. M. & Hajek, A. E. (2018). Lymantria dispar larval necropsy guide. USDA Forest Service, General Technical Report NRS-179.

- CABI. (2021). Invasive species compendium: Lymantria dispar (gypsy moth). CAB International.

- Coleman, T. W., Haavik, L. J., Foelker, C., & Liebhold, A. M. (2020). Gypsy moth [Forest Insect & Disease Leaflet 162]. U.S. Department of Agriculture.

- Davis, R. S. & Jones, V. P. (2011). Fall webworm [Fact sheet ENT-148-11]. Utah State University Extension.

- Keena, M. A. & Richards, J. Y. (2020). Comparison of survival and development of gypsy moth Lymantria dispar L. (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) populations from different geographic areas on North American conifers. Insects 11, 260.

- Molet, T. (2016). CPHST pest datasheet for Lymantria dispar asiatica. USDA APHIS-PPQ-CPHST.

- Streifel, M. A., Tobin, P. C., Kes, A. M., & Audema, B. H. (2019). Range expansion of Lymantria dispar dispar (L.) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) along its north-western margin in North America despite low predicted climatic suitability. Journal of Biogeography 46, 58-69.

- Utah Department of Agriculture and Food (UDAF). (2019). UDAF urges vigilance in Christmas tree inspection of invasive species.

- UDAF. (2021). R68-14-2: Quarantine pertaining to gypsy moth - Lymantria dispar. Utah Department of Agriculture and Food, Plant Industry.

- Wallner, W. E. (2000). Lymantria dispar Asian biotype [EXFOR pest report]. Exotic Forest Pest Information System for North America.

- USDA Hungry Pests:

- https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/resources/pests-diseases/hungrypests/ the-threat/asian-gypsy-moth/asian-gypsy-moth

- https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/resources/pests-diseases/hungrypests/ the-threat/hp-egm/hp-egm

- Don’t Move Firewood:

- https://www.dontmovefirewood.org/pest_pathogen/asian-gypsymoth- html-0/

- https://www.dontmovefirewood.org/pest_pathogen/europeangypsy- moth-html/