Powdery Mildew on Vegetables

April 2021

Nick Volesky, Vegetable IPM Associate • Marion Murray, Extension IPM Specialist • Claudia Nischwitz, Extension Plant Pathologist

Fig. 1. Conidia (spores) that form from hyphae cause infections throughout the growing season. Image courtesy of J. Schlessselman, American Pytopathological Society.

Fig. 2. Erysiphe pisi on a pea foliage.

Fig. 3. Golovinomyces cichoracearum on winter squash.

Fig. 4. Leveillula taurica on pepper. Image courtesy of Dr Parthasarathy Seethapathy, Tamil Nadu Agricultural

University, Bugwood.org.

Fig. 5. G. cichoracearum on lettuce. Image courtesy of Gerald Holmes, Strawberry Center, Cal Poly San Luis

Obispo, Bugwood.org.

Fig. 6. Podosphaera xanthii on melon. Image courtesy of Tom Isakeit, Texas A&M University Extension.

Fig. 7. L. taurica on onion.

Fig. 8. Erysiphe heraclei on carrot foliage.

Fig. 9. Erysiphe cruciferarum on kale.

Fig. 10. L. taurica on tomato foliage. Image courtesy of Dollymoon, wikimedia commons.

Fig. 11. P.xanthii on summer squash.

Fig. 12. Erysiphe polygoni on bean foliage. Image courtesy of Howard F. Schwartz, Colorado State University,

Bugwood.org.

Fig. 13. G. cichoracearum on potato. Image courtesy of Phil Hamm, Pacific Northwest Handbooks.

Quick Facts

- Powdery mildew is widespread in Utah and affects many vegetable, fruit, and landscape plants. There are several species of powdery mildew fungi, and typically they target just a single host, or only hosts in related plant families.

- Powdery mildew is easily identifiable as white, “powdery” patches on the surface of leaves.

- Utah’s environment is favorable to this disease. It thrives in warm temperatures, humid plant canopies, and poor airflow.

- Manage powdery mildew by growing resistant varieties, using cultural pest management practices, and applying organic fungicides such as sulfur or potassium bicarbonate, or conventional fungicides such as chlorothalonilor a strobilurin.

Powdery mildew is one of the most easily recognized fungal plant diseases. It is categorized by spots or patches of white-to-gray powder-like growth on foliage, stems, or fruit. Roughly 700 species exist that infect grasses, ornamentals, weeds, fruit trees, landscape trees, shrubs, and vegetables. The closely-related species of fungi that cause powdery mildew are host-specific (Table 1), meaning they cannot survive without the proper host. Powdery mildew fungi spread in conditions of low rainfall and hot temperatures, making Utah’s climate the perfect environment.

Table 1. Species of powdery mildew and their vegetable hosts in Utah

| Powdery Mildew Species | Host Crops |

|---|---|

| Erysiphe cruciferarum | broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, kale, and Brussel's sprouts |

| Erysiphe polygoni | chard, beet, and beans |

| Erysiphe pisi | pea |

| Erysiphe heraclei | carrot and celery |

| Golovinomyces cichoracearum | cucumber, melon, summer squash, and winter squash |

| Podosphaera xanthii | cucumber, melon, summer squash, and winter squash |

| Leveillula taurica | onion, pepper, and tomato |

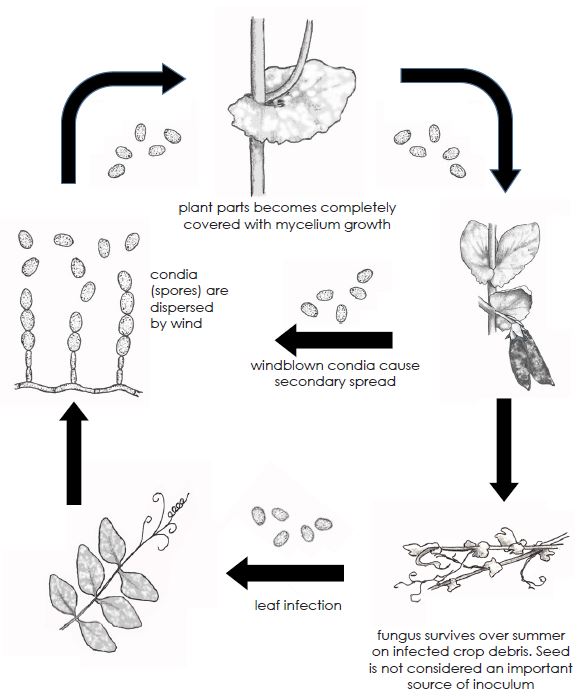

Disease Cycle

Powdery mildew fungi are considered “obligate parasites” meaning that they cannot grow without a living host.

Late in the growing season, the powdery mildew fungus initiates sexual reproduction in some plant species. This sexual phase forms resting structures on foliage and other plant parts that are important for overwintering survival. The resting structures are fruiting bodies (chasmothecia) that contain the overwintering spores and are resistant to low temperatures and drought. With warm humid conditions in spring, chasmothecia release wind-blown spores that cause primary infections on susceptible hosts.

Unlike most other fungi, powdery mildew spores can spread and germinate without the presence of moisture. When a spore lands on a suitable host, it germinates and hyphae colonize the leaf surface and specialized hyphal structures (haustoria) penetrate host cells to absorb nutrients. Within 7 to 10 days of this primary infection, the characteristic mix of white mycelium and spores (conidia) is visible. In some powdery mildew species (like those in the Leveillula group), the hyphae grow within host tissue.

The massive amount of conidia that form after the primary infection results in multiple secondary infections throughout the growing season. Under conditions of warm and dry weather (75–85° F) with high evening humidity, rapid spread can lead to an epidemic, especially for plants grown closely together. Older foliage is more susceptible to powdery mildew and will likely be the first infected.

Injury

In general, infected plants have white-to-gray patches with powder-like growth on the upper- or under-side of leaves. Less frequently, powdery mildew may also occur on young stems, buds, flowers, and young fruit. The presence of powdery mildew reduces photosynthesis and results in reduced fruit yield and low-quality fruit due to reduced sugar levels. Infections on fruit affect marketability by reducing the product’s aesthetics.

Heavily infected vegetable crops may also show symptoms of leaf curling, chlorosis (yellowing), and possible dieback. Fruit yield declines and fruits are smaller and exposed to sunscald from lack of canopy cover. Only melon and cucumber fruits are occasionally directly infected by the pathogen, where the white mycelium is visible on the skin.

Monitoring

Early detection of powdery mildew is critical, so it is important to consistently scout plants for disease. Soon after planting, commercial growers should randomly select 5–10 different locations in the field once a week and check plants for powdery mildew. Home gardeners may be able to check all plants. Observe the tops and bottoms of older and mature leaves first. Focus on areas of the field that are densely planted, crowded by weeds, vigorously growing, and shaded.

Management

Since powdery mildew can diminish yield, it is important to be proactive with management to reduce disease pressure.

Cultural Control

- Plant resistant varieties. Several varieties of vegetable crops are labeled with some level of resistance against powdery mildew (Table 2). Podosphaera xanthii has several races, and varieties labeled as resistant may not be resistant to all races. It is currently unknown what specific races are present in Utah.

- After harvest, remove or plow infected plant material. Powdery mildew overwinters on plant debris and removal can reduce disease occurrence the following season. Remove and destroy all infected parts of the plant (leaves, branches, vines, and infected fruit). Do not place infected plant material in composting piles. Compost pile temperatures are not high enough to kill the pathogen.

- Increase plant spacing. Properly spaced plants will have better air movement, reducing the canopy humidity that can trigger powdery mildew infections.

- Morning irrigation will allow excess moisture to dry from the ground and leaves, reducing evening humidity. Where possible, switch to drip irrigation.

Table 2. Examples of Vegetable Varieties Resistant to Powdery Mildew

| Crop | Resistant Varieties |

|---|---|

| Bean | Contender, Provider, Slenderette |

| Carrot | Bolero |

| Beet | Kestrel, Red Acre, Solo |

| Cucumber | Adam Gherkin, Amiga, Arkansas Little Leaf, Bristol, Bush Pickle, Calypso, Citadel, Cool Breeze II, County Fair, Cross Country, Darlington, Dasher II, Diomede, Diva, Eureka, Fanfare, Fancipak, H-19 Little Leaf, Harmonie, Iznik, Jackson Supreme, Jade, Saladmore, Salt and Pepper, Sassy, Seminis, Slice More, Socrates, Southern Delight, Suyo Long, SV4719CS, Sweet Slice, Talladega, Tasty, Turbo, Tyria, Unagi, Unistars, Vlasstar |

| Melon | Afterglow, Ambrosia, Aphrodite, Arava, Astound, Athena, Atlantis, Avatar, Camino Europa, Cleopatra, Crescent Moon, Da Vinci, Delicious, Delightful,, Divergent, Duchess, El Gordo, Escorial, Full Moon, Hannah’s Choice, Infinite Gold, Lilliput, Lillly, Milan, Orange Sherbet, Rockstar, San Juan, Sapomiel, Savor, Shockwave, Sierra Gold, Solstice, Sugar Cube, Torpedo, Sugar Rush, Sun Jewel, Verona |

| Peas | Avalanche, Dakota, Feisty, Green Arrow, Knight, Maestro, Mr. Big, Oregon Giant, Oregon Sugar Pod II, Penelope, Petite Snap—Greens, PLS 141, PLS 595, Super Sugar Snap |

| Pumpkins | Benchmark, Big Doris, Blanco, Blaze, Capital, Cargo PMR, Charisma PMR, Cinnamon Girl PMR, Cougar, Denali, Apogee, Dynasty, Early Giant, Early Giant, Early King, Edison, Eureka, Everest, Gemini, Gold Medal, Grizzly Bear, Gumdrop PMR, Jill-Be-Little, Magnum, Mellow Yellow, Mustang, Orion, Pegasus, Pipsqueak PMR, Porcelain Doll, Renegade PMR, Ritz, Rival PMR, Shiver, Spark, Sunlight PMR |

| Summer Squash | Golden Girl, Sebring Premium, Sligo, Golden Glory, Mabel Dunja, Green Machine, Spineless Perfection, Yellowfin, Golden Glory, Cue Ball, Desert, Gold Star |

| Winter Squash | Autumn Delight, Autumn Frost, Autumn’s Choice, Black Bellota, Bon-Bon, Bugle, Bush Delicata, Butterbaby, Butterscotch PMR, Celebration, Golden Butta Bowl, Honey Bear, JWS 6823 PMR, Metro PRM, Narragansette, Speckled Pup, Starry Night PMR, Sun Spot, Table Treat, Taybelle PM, Tiptop PMR, Unique, Waldo PMR |

| Tomato | Climstar, Frederik, Geronimo, Granadero, Rebelski |

| Pepper | Carlomagno, Pizarro |

| Spinach | Mouflon |

Chemical Control

Many fungicides (both organic and synthetic) are available for commercial operations and home gardeners. Consider fungicide treatments when the first sign of powdery mildew is found. Repeated applications should occur every 7–10 days (or according to label recommendations).

Note that some products and product combinations can cause phytotoxicity (plant injury), such as:

- Oils applied at temperatures over 85°

- Sulfur applied at temperatures over 80° F

- Mixing oil and sulfur or applying within 2 weeks of each other

Fig. 14. Simple diagram of the powdery mildew disease cycle. Image courtesy of Chart referenced from extensioaus.com.au

Fig. 14. Simple diagram of the powdery mildew disease cycle. Image courtesy of Chart referenced from extensioaus.com.au(Illustrations by Kylie Fowler).

Table 3. Examples of Fungicides Registered for Commercial Use on Vegetable Powdery Mildew in Utah

| Active Ingredient | Brand Name | Cucurbits | Root Crops | Leafy Greens | Solanaceae Crops |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copper sulfate | Cuprofix Ultra | X | X | X | X |

| Copper hydroxide + mancozeb | Mankocide | X | (see label) | X | X |

| Sulfur | CosavetO, Microthiol DisperssO, Micro SulfO, ThioluxO | X | X | X | X |

| Chlorothalonil | Bravo, Echo, Equus | X | (see label) | X | |

| Benzovindiflupyr + difenoconazole | Aprovia Top | (see label) | |||

| Propiconazole | AmTide Propiconazole 41.8% EC | X | |||

| Cyprodinil + fludixonil | Switch | X | X | X | X |

| Azoxystrobin | Quadris | X | X | ||

| Bacillus mycoides | LifeGardOB | (see label) | |||

| Bacillus subtilis | Serenade ASOOB | X | |||

| Reynoutrai sachalinensis extract | Regalia CGOB | X | |||

| Phosphorous acid salts | OxiPhos, Fospite B | X | X | X | X |

| Hydrogen peroxide + peroxyacetic acid | OxiDate 2.0 | X | X | X | X |

| Neem oil | EcoWorksB | X | X | X | X |

| Mineral oil | PureSpray GREENO, Ultra-Pure Oil Horticultural InsecticideO, SuffOil-XO, TriTekO | X | |||

| Soybean oil | Bionatrol-MO | X | X | X | X |

| Potassium bicarbonate | KaligreenO, MilStop SPO | X | (see label) | (see label) | X |

Table 4. Examples of Fungicides Registered for Home Use on Vegetable Powdery Mildew in Utah

| Active Ingredient | Brand Name | Cucurbits | Root Crops | Leafy Greens | Solanaceae Crops |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copper | Natural Guard Copper Soap, Monterey Lqui-Cop | X | X | X | X |

| Sulfur + pyrethrins | Natria Insect Disease & Mite ControlB, Bonide Tomato & Vegetable 3-in-1 | X | X | X | |

| Chlorothalonil | Fertilome Broad Spectrum Landscape & Garden Fungicide, Hi Yield Vegetable, Flower Fruit & Ornamental Fungicide, Ortho Max Garden Disease Control | X | X | X | |

| Myclobutanil | Spectracide Immunox Multi-Purpose Fungicide | X | X | ||

| Potassium salts of fatty acid | Safer Brand Tomato & Vegetable 3-in-1B | (see label) | |||

| Bacillus subtilis strain QST 713 | Serenade Garden Disease ControlOB | (see label) | |||

| Oils: mineral-based | Bonide All Seasons Horticultural OilB | X | (see lable) | X | X |

| Oils: plant-based | Monterey All Natural 3-in-1B, Arborjet Eco-1 Fruit & Vegetable SprayOB | (see label) | |||

References and Further Reading

- Schilder, A. (2014). How to get the most out of your fungicide sprays. Michigan State University Extension.

- Bogran, C., Ludwig, S., & Metz, B. (n.d.). Using Oils as Pesticides. Texas A&M University.

- Cannon, C., Murray, M., Schaible, C., & Beddes, T. (n.d.). Vegetable pests of Utah. Utah State University Extension.

- Cannon, C., Murray, M., Alston, D., & Drost, D. (2018). 2018 Utah vegetable production and pest management guide. Utah State University Extension

- Davis, R. M., Gubler, W. D., & Koike, S. T. (2008, November). Powdery mildew on vegetables. Pests Notes, Statewide Integrated Pest Management Program, University of California.

- Flint, M. L. (2018). Pests of the garden and small farm: A growers guide to using less pesticide. University of California, Agriculture and Natural Resources.

- Grabowski, M. (2018). Powdery Mildew of Cucurbits [Fact sheet]. University of Minnesota Extension.

- Howell, J. C. (Ed.). (2009). Vegetable management guide (New England Region). New England Extension Systems.

- Hudelson, B. (2010, February). Powdery mildew (vegetables) [Fact sheet]. University of Wisconsin Extension

- Keinath, A. P. (2018). Cucurbit downy mildew management for 2018 [Fact sheet]. Clemson Cooperative Extension.

- Klein, C., & Gilsenan, F. (2016). Vegetable gardening: The complete guide to growing more than 40 popular vegetables in any space. I-5 Press.

- Lutton, J., & Rosenberger, S. (2015). Cucurbit disease field guide (C. Kurowski & K. Conn, Eds.). Seminis.

- Olsen, W. M. (2011, January). Powdery mildew [Fact sheet]. University of Arizona Extension.

Image Credits

1 J. Schlessselman, American Pytopathological Society

2 Long Island Horticultural Research & Extension Center (Cornell University)

4 Dr Parthasarathy Seethapathy, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Bugwood.org

5 Gerald Holmes, Strawberry Center, Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, Bugwood.org

6 Tom Isakeit, Texas A&M University Extension

9 alchetron.com

10 Dollymoon, wikimedia commons

12 Howard F. Schwartz, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org

13 Phil Hamm, Pacific Northwest Handbooks

14 Chart referenced from extensioaus.com.au (Illustrations by Kylie Fowler)

Related Research