Water-wise Landscape Design

Why Design?

Every landscape within the built environment is either intentionally or unintentionally designed. Simply letting things happen is a form of design—but one that often generates undesirable results. Following a landscape design process allows you to understand and explore multiple alternative designs relatively quickly. Making changes to a drawing can happen in minutes and with little effort; however, making a change after installation in your landscape is time-consuming and expensive. A landscape design also establishes a framework within which you can add details, modify maintenance efforts, and make adjustments incrementally over time. Landscapes evolve, and a good landscape design accounts for this evolution and embraces the landscape’s inevitable growth. Finally, a landscape design helps you be intentional about where, when, and how you use water within your landscape.

The Landscape Design Process

The Merriam Webster Dictionary defines a process as “a series of actions that produce something or that lead to a particular result.” Similarly, a water-wise landscape design process provides a logical sequence of steps intent on guiding you to a desirable result. The design process creates a framework for gathering and organizing information and ideas and then prompts you to use them at the right time and in an appropriate way. Finally, this process will help you explain the logic behind your resulting design ideas to yourself and those you enlist to help you implement your design. For more information about the landscape design process, USU Extension provides an in-depth, online landscape design course called “Design 4 Everyone.” The course provides illustrations and videos that teach a four-step approach to the design process. The process steps include: creating a base map and conducting a site inventory and analysis, establishing goals, creating functional diagrams, and utilizing design principles and elements.

Step #1 Understand the Hydrology of Your Site

Getting to know your site is an important first step in making future design decisions. For more information, regarding creating a base map and conducting a site inventory and analysis.

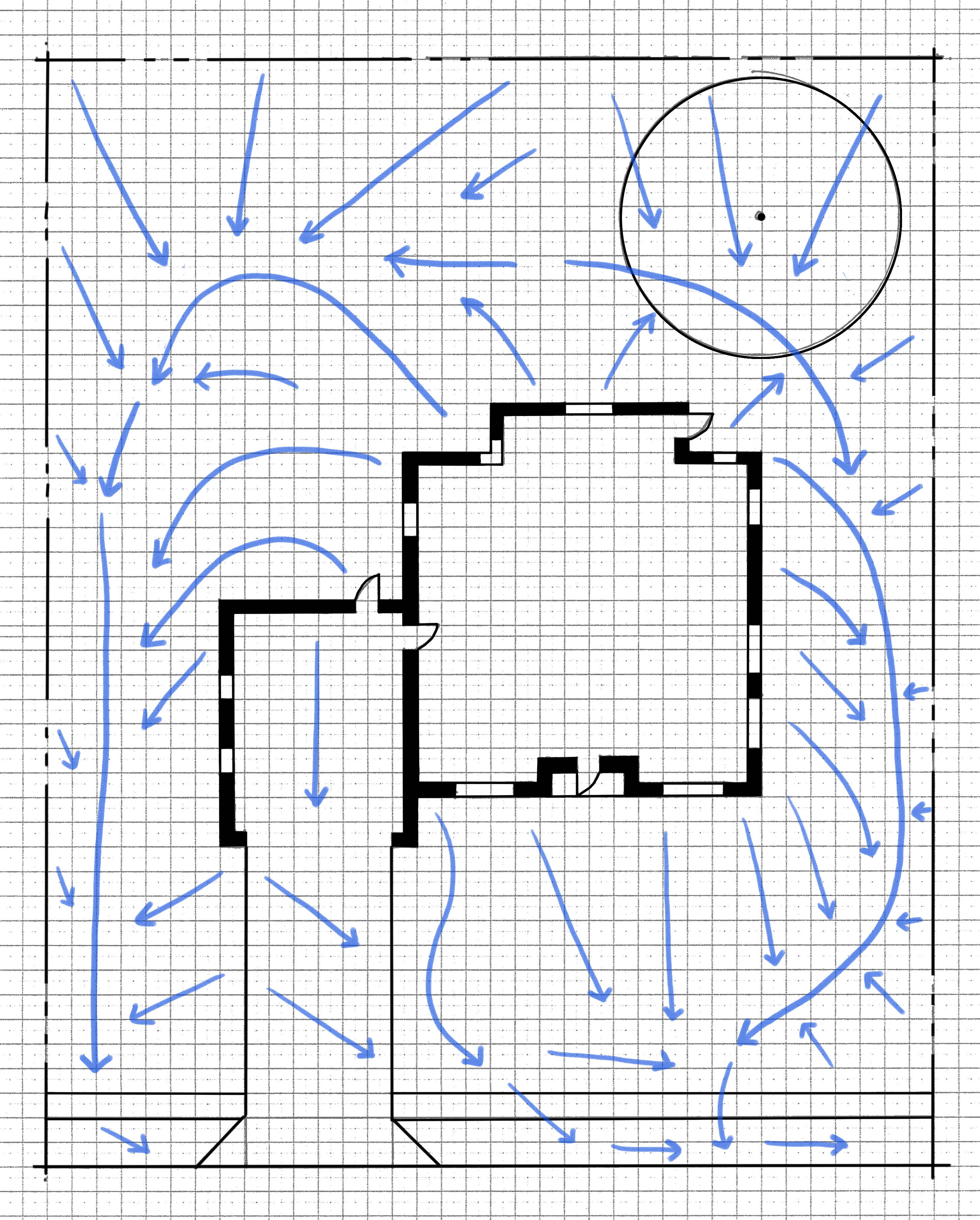

When it comes to water-wise landscape design, getting to know how water moves across the land you are planning to modify, also known as a “site,” will help you develop strategies to put the water already falling on your site to good use. The shape of the land influences where water moves and when, where, and how it soaks into the ground. To better understand the water movement on your site, get a base map of your site and use a blue colored pencil to draw arrows showing where water is most likely to go during a precipitation event. Ask yourself, how does the land naturally channel and move water on my site? Pay attention to areas where water runs off or is gathered from hardened surfaces like a roof or driveway. Where are there low areas that are wet after a rainstorm? Circle these areas on your base map.

Look for areas where the climate allows water to persist longer. Note areas that face north and east or are located in shaded areas such as the north side of your home or in the shadow of your neighbors’ trees. These areas are typically cooler and wetter than the surrounding landscape due to adjacent structures or the direction they face. Also, think about what areas of your site face south and west. These areas are often drier due to longer sun exposure during the day and throughout the seasons. Look for other areas that are dry and hot and take note of them on your base map.

Understanding how water moves within and across your site will help you identify areas naturally suited for specific activities, design elements, and plants that require different water needs. This understanding will also help you avoid drainage problems, installing drainage systems, and allow you to more efficiently use the water already falling on your site.

Step #2 Organize Your Landscape for Functionality

A well-designed residential landscape is one that unites its existing assets with the desires and goals of the homeowner. For specific information regarding setting goals and establishing a list of desired landscape components, see the creating a components list and ideal functional diagrams fact sheets in the Landscape Design Series. Knowing what activities, landscape elements, and uses your landscape will facilitate helps you use limited water resources only where your desired activities require them. Too often, landscape designs that lack a robust component list end up covered in water-intensive turf grass simply because there was no other use designated for the area. Taking time to develop a comprehensive component list and ideal functional diagram ensures that your landscape has what you need and want, located where you want it.

Identify areas where certain activities are already facilitated by the natural environment you observed in Step 1. For example, a hot area where the sun is overly intense may be an ideal location for a sunny seating area, a garden, a graveled vehicle parking area, or a greenhouse rather than the ideal location for a planted area. Conversely, a shaded area near the home’s front entrance and adjacent to the roof’s downspout might be an ideal location for a lush and colorful perennial flower bed. As you organize your landscape, make sure you are considering the function and relationship of each component and how they utilize the existing environmental conditions of the site.

The Jordan Valley Water Conservation District’s “Localscapes” program provides a helpful method to organize your landscape. They suggest organizing the landscape around a central open shape that establishes a core focal point. Second, locate gathering areas within the landscape to facilitate social interactions within your yard. Third, establish activity zones that allow for all of the activities and events you want to enjoy in your landscape. Fourth, link these spaces using permeable or hard surface paths. Finally, use the spaces between the first four elements as homes for the plants that will make your yard come alive. Use these organizing steps to help you create a hierarchy of importance as you work to locate your components in advantageous areas.

Step #3 Create Spaces

As you begin to organize your components within the landscape, it is important to remember you are creating outdoor spaces. In the same way the space in a building is organized into a series of interior rooms of different volumes and proximity to other rooms, landscapes consist of outdoor rooms or spaces containing different uses and associated volumes. Vertical and horizontal structures and/or plants can be used to effectively create three dimensional spaces within your landscape. It may help to imagine fences, walls, shrubs, and trees as walls; envision pergolas, arching tree branches, or shade structures as ceilings as you create outdoor spaces. Take care to match the shape, feel, and volume of the space with the intended use. Turf should be used to facilitate activities and events where high use requires the soil to be covered and held in place with roots. However, turf is often located in areas where it is difficult to effectively irrigate, such as on steep slopes or in side yards where it is rarely even walked on. Look for ways to use turf only where it is needed, and find alternatives where it is not.

Step #4 Establish Hydrozones

Hydrozones are an effective way to utilize the natural assets of your site, organize spaces, and maximize the potential water efficiency in your irrigation system. A hydrozone is an area that uses the same irrigation zone and activities, plant types, and maintenance requirements, all grouped together. Intentionally grouping similar elements together allows you to strategically plan for their similar water requirements. Landscapes where hydrozones do not exist typically require irrigation across the entire landscape to compensate for the most water-consuming plants. This approach typically results in overwatering.This kind of landscape is also frustrating to attempt to maintain and efficiently water.

To establish hydrozones you can organize your landscape using a simple 4-zone classification system: Zone 0 - No irrigation; Zone 1 - little irrigation (once a month); Zone 2 - some irrigation (twice per month); Zone 3 - moderate irrigation (weekly); Zone 4 - high irrigation (twice per week). For example, in areas you identified as naturally dry, you could create a grouping of Utah natives that need little to no irrigation and locate them within the naturally harsh, dry areas of your landscape. You might place an area of turf in a uniformly sunny area in an easily irrigated shape and designate it as a Zone 4 high irrigation hydrozone. Hydrozones can be enhanced by utilizing or changing the site’s topography to capture additional water or customizing the soil amendments and irrigation delivery system and volume for each hydrozone. Intentionally establishing hydrozones in the design phase allows you to design or modify your irrigation system in future phases to adequately serve each different area.

Step #5 Capture What You Can, Ration What You Can’t

When designing your landscape, you may also want to consider ways to capture and reuse water or mimic the natural water cycle that occurred on your site before you were there. Instead of allowing water to run off your site and into the street, identify areas within your hydrozone map where excavating the soil and shaping the ground could allow water to infiltrate into the soil, roots, and water table below.

Select materials that will allow water to infiltrate rather than run off of hardened surfaces. Rather than use impervious materials such as cement, consider pavers, gravel, or flagstone that allows water to percolate through the exposed cracks and enter the soil below. Where impervious surfaces do exist, allow water to drain into the landscape and establish hydrozones that take advantage of the water.

Rain gardens connected to gutter downspouts but sloped away from structures provide another opportunity to use rainwater on the site. Your design may create a space for a rainwater barrel or even a cistern where local ordinances allow. These containers store rainwater for use later in the season and help minimize the amount of outside irrigation required for your landscape. After using whatever moisture that naturally falls on your site, you should design so that your supplemental irrigation system is as efficient as possible.

References

- Meyer, S. E. (2009). Landscaping on the new frontier: Waterwise design for the Intermountain West. Utah State University Press.

- Dieter, C. A., Maupin, M. A., Caldwell, R. R., Harris, M. A., Ivahnenko, T. I., Lovelace, J. K., . . . Linsey, K. S. (2018). Estimated use of water in the United States in 2015 (Circular 1441). U.S. Geological Survey, U.S. Department of the Interior. http://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/cir1441

Authors

Related Research

Utah 4-H & Youth

Utah 4-H & Youth