Substance Use Disorders and Youth: How Parents and Communities can be Involved

This factsheet examines the effects of substance use on brain development in youth, the impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) on youth substance use, and interventions parents and community members can use to reduce their children’s risk.

Introduction to Substance Use Disorders and Youth

The risks associated with substance use begin before someone starts using substances (Compton et al., 2019). Moreover, the initiation of substance use at an earlier age increases an adolescent’s susceptibility to developing a Substance Use Disorder (SUD) later in life (DuPont et al., 2018). Specifically, the use of prescription opioids in late high school is associated with non-medical prescription opioid use in adult life (Martins et al., 2017). In 2016, 1 in 10 adolescents ages 15-24 years, died of an opioid related cause (Robinson & Wilson, 2020). Unfortunately, there can be a false sense of security and safety in prescription drugs. These feelings can be explained by the direct-to-consumer advertising by pharmaceutical companies, and belief of safety in prescriptions even for non-medical uses (Martins et al., 2017).

Effects of Substances on Brain Maturation and Development

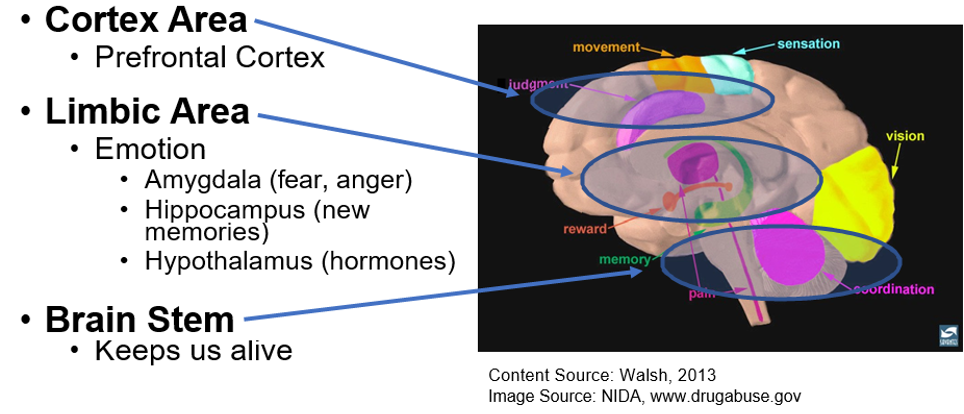

Development of the limbic system (i.e., the reward and emotional response system) in the brain occurs sooner than the cortical areas of judgement, decision-making, and impulse control (Compton et al., 2019). This timeline of development means the developing years are critical to avoiding risk in adolescence and into adulthood. This could also mean that starting substance use in early life could cause the limbic system to have high levels of activation before fully mature. This results in the brain connecting substances with pleasure (Compton et al., 2019).

See Figure 1 below, for a graphic outlining the functions of the brain sections discussed including Cortex Area, Limbic Area, and Brain Stem.

Figure 1. From NIDA.

Source: Burrow-Sánchez, J. (2019, June 19). Understanding the Social and Biological Aspects of Adolescent Development: The Implications for Substance Use Prevention. https://utahprevention.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/burrow_sanchez_bryce.pdf.

The interaction between brain maturation, environment, and genetics can impact the possibility of a SUD (Compton et al., 2019). Prenatal exposure to substances, as well as stressful family environments in childhood, strengthen the risks for substance use and addiction. Additionally, later in childhood, peer environments, and neighborhood and school structures can have a considerable impact on substance use (Compton et al., 2019). Social and physiological transitions in the sensitive adolescence years cause youth to be more susceptible to the effects of substances than young adults (Martins et al., 2017). The crucial developmental years of youth are harmed when powerful substances enter the body (Martins et al., 2017).

Additionally, research has shown that the earlier an adolescent is exposed to substances (e.g., tobacco, alcohol, marijuana) the higher their odds of developing a SUD later in life (Hayathbakhsh et al., 2008). The same connection has been demonstrated with opioids, with Robinson and Wilson (2020) finding that that early initiation of opioid use is linked to greater risk for developing an Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) in the future.

Experiences that could Initiate a Substance Use Disorder in Youth

Research has shown that negative experiences in childhood could initiate an opioid or substance use disorder for youth (Compton et al., 2019). A stressful environment has been proven to increase a young person’s disposition to mental illness and the likelihood of substance use and dependence later in life (Compton et al., 2019).

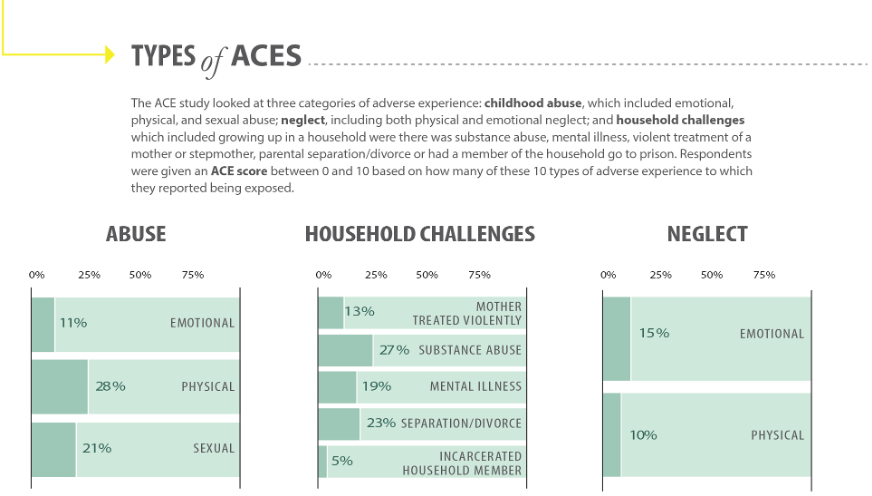

Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACEs, can impair a developing child’s (0-17 years) cognitive, emotional, and social development (Stein, et al., 2017). Furthermore, ACEs can also contribute to neurological changes such as memory, attention, the ability to understand input from senses, and brain development impairments (Stein, et al., 2017). The ACE scale identifies patients at elevated risk for injection drug use and overdose and can also be used for measuring the risk a youth has for early initiation of opioid use (Stein, et al., 2017). ACEs are measured by specific incidents, with each traumatic experience being one point on the scale (Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), 2020). Such traumatic experiences in childhood could result in a variety of unfit and dysfunctional coping mechanisms including substance misuse across the life span and early age of injection drug use (Stein, et al., 2017).

See Figure 2 below, for the 10 types of ACEs that are organized into categories including: Abuse, Household Challenges, and Neglect.

Figure 2. From the CDC citation below.

Note: Research that use Wave 1 and/or Wave 2 data may contain slightly different prevalence estimates. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Kaiser Permanente. The ACE Study Survey Data [Unpublished Data]. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016.

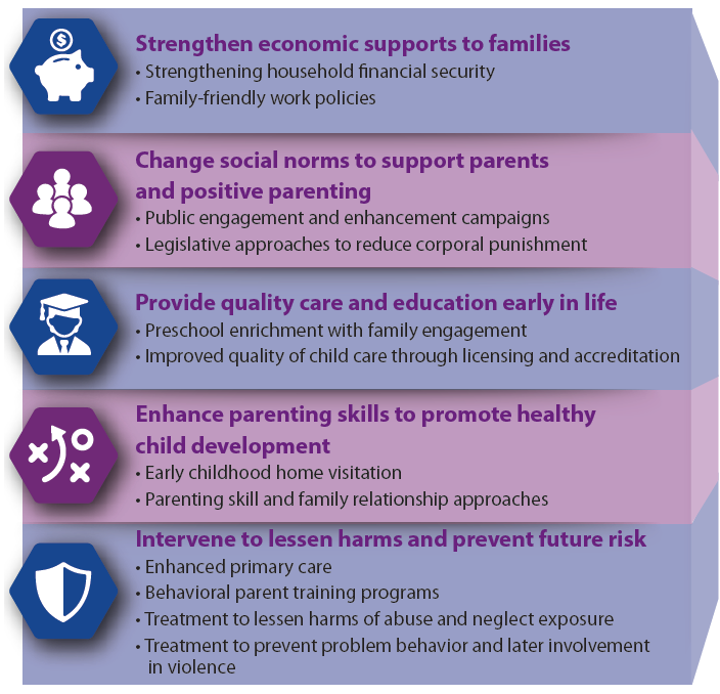

See Figure 3 below, for suggestions on how to prevent Adverse Childhood Experiences in different situations.

Figure 3. From the CDC citation below.

Source: Fortson, B. L., Klevens, J., Merrick, M. T., Gilbert, L. K., & Alexander, S. P. (2016). Preventing child abuse and neglect: A technical package for policy, norm, and programmatic activities. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Using prescription opioids for non-medical purposes increases the risk of developing an OUD. 80% of youth ages 12-21 years who use heroin indicate that they started with non-medical opioid prescription use between ages 13-18 years (Martins et al., 2017). With youth, opioid use commonly begins with the use of prescription opioids retrieved from family, friends, and personal medical prescriptions (Robinson & Wilson, 2020). Most youth obtain opioids from a prescription following a dental visit (Robinson & Wilson, 2020).

Sports involvement has also been shown to influence how youth are introduced to opioid and substance use (Ford et al., 2017). Being involved in sports is a contributing factor to the non-medical use of prescription drugs, which is the most common form of substance use among adolescents and young adults. In particular, Ford et al. (2017) found that injured male athletes were at the greatest risk for using prescriptions for non-medical purposes. Having a history of injuries and concussions can significantly contribute to when a person initiates non-medical use of prescription drugs). Even being involved in sports, especially contact sports, can contribute to the chances of using substances for non-medical purposes (Ford et al., 2017).

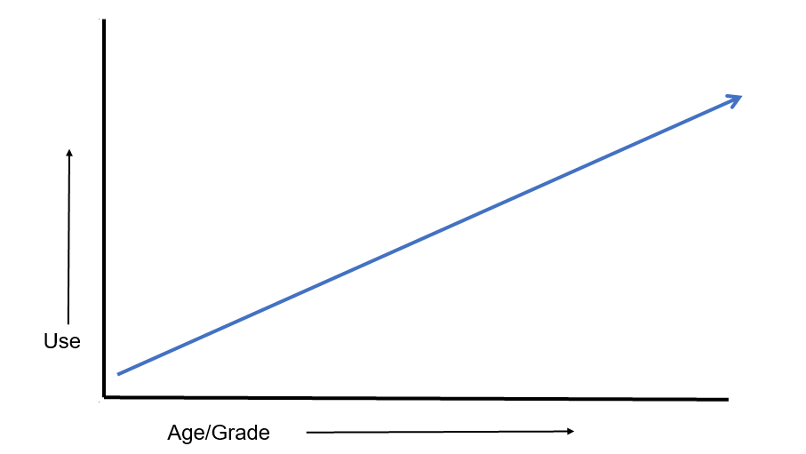

See Figure 4 below, for a graphical representation of the correlation between age/grade of substance use start and use of substances.

Figure 4.

Source: Burrow-Sánchez, J. (2019, June 19). Understanding the Social and Biological Aspects of Adolescent Development: The Implications for Substance Use Prevention. https://utahprevention.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/burrow_sanchez_bryce.pdf.

Screening and Family Support for Youth

Screening for all substance use in youth is important in addressing prevention needs. The use of one substance is often associated with the use of other substances in youth (DuPont et al., 2018). Polysubstance use, or the use of multiple classes of substances, commonly develops into a SUD. This transition from using one substance to many substances results more frequently in a SUD than single substance use (DuPont et al., 2018).

The use of tools such as Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT), recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics, could be utilized by pediatricians and other medical professionals in identifying opioid or substance use in youth (Robinson & Wilson, 2020). SBIRT is an effective framework strategy that is suggested for use in pediatric primary care routine supervision visits to identify and manage substance use. Yet less than half of pediatricians who see youth use proper screening tools for identifying substance use (Robinson & Wilson, 2020). Studies show that evaluations of risk in youth are based solely on clinical impressions by pediatricians who can often underestimate substance use and fail to identify risky use in youth. Research is ongoing in identifying specific youth measures in screening, implementing and integrating SBIRT in the primary care setting; however, overall evidence from the introduction of SBIRT in clinical settings, with youth specific provisions, indicates positive short-term outcomes for youth (Robinson & Wilson, 2020). SBIRT has shown efficacy for adults, but there is an immediate, severe need for research on how to best screen, implement, and integrate SBIRT into clinical practice for youth (Robinson & Wilson, 2020). Consider talking to your primary care provider about SBIRT in identifying unhealthy substance use.

Physicians Robinson & Wilson (2020) describe the role that primary care visits can play in educating parents and adolescents about the prevention of OUD and other SUDs. In addition to the education that is currently being provided in primary care visits, they

recommend that additional education should be provided related to overdose (prevention, recognition, and response), the hazards of injecting substances in used needles (including infection by communicable disease), and other harm reduction techniques (Robinson & Wilson, 2020).

What Families of Youth with a Substance Use Disorder can do

Engaging in the treatment process by learning about the young person’s treatment plan has positive results and outcomes (Robinson & Wilson, 2020). Families should also carry naloxone (an opioid overdose reversal drug) as a precaution (Robinson & Wilson, 2020). Parents are encouraged to learn more about these topics through their child’s primary care provider and other local and national resources. Remember risk aversion is essential for the developing brain, adolescents are particularly susceptible to drug effects because of the physiological and social transitions experienced at this age (Martins et al., 2017). Parents have the ability to reduce a young person’s risk of substance use and to give our youth a more favorable future (Long Foley et al., 2004).

Parent and Community Resources

| Organization | Website |

|---|---|

|

Al-Anon/Alateen |

|

|

Communities That Care |

|

|

CRAFT Family Support |

|

|

Naloxone |

naloxone.utah.gov/ |

|

National Harm Reduction Coalition |

harmreduction.org/ |

|

National Substance Use Treatment Locator |

findtreatment.gov/ |

|

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (1-800-723-8255) |

suicidepreventionlifeline.org/ |

| Parents Empowered | parentsempowered.org/ |

| SafeUT | safeut.med.utah.edu/ |

| SMART Recovery | myusara.com/smart-recovery-at-usara/ |

| Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) | samhsa.gov |

| The Opidemic | |

| United Way (2-1-1) | 211utah.org/ |

| Use Only as Directed | useonlyasdirected.org/ |

| USU Health Extension: Advocacy, Research Teaching (HEART) Initiative | extension.usu.edu/heart/ |

| Utah Coalitions for Opioid Overdose Prevention | ucoop.utah.gov/ |

| Utah Department of Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health | dsamh.utah.gov/ |

| Utah Poison Control Center

(1-800-222-1222) |

poisoncontrol.utah.edu/ |

| Utah Prevention Coalition Association | utahprevention.org/ |

| Utah Support Advocates for Recovery Awareness | myusara.com/ |

References

- Burrow-Sánchez, J. (2019, June 19). Understanding the Social and Biological Aspects of Adolescent Development: The Implications for Substance Use Prevention. https://utahprevention.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/burrow_sanchez_bryce.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, April 3). Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Kaiser Permanente. The ACE Study Survey Data [Unpublished Data]. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016.

- Compton, W. M., Jones, C. M., Baldwin, G. T., Harding, F. M., Blanco, C., & Wargo, E. M. (2019). Targeting Youth to Prevent Later Substance Use Disorder: An Underutilized Response to the US Opioid Crisis. American Journal of Public Health, 109, S185–S189. https://doi-org.dist.lib.usu.edu/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305020

- DuPont, R. L., Han, B., Shea, C. L., & Madras, B. K. (2018). Drug use among youth: National survey data support a common liability of all drug use. Preventive medicine, 113, 68–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.05.015

- Ford, J. A., Pomykacz, C., Veliz, P., McCabe, S. E., & Boyd, C. J. (2018). Sports involvement, injury history, and non-medical use of prescription opioids among college students: An analysis with a national sample. American Journal on Addictions, 27(1), 15–22. https://doi-org.dist.lib.usu.edu/10.1111/ajad.12657

- Fortson, B. L., Klevens, J., Merrick, M. T., Gilbert, L. K., & Alexander, S. P. (2016). Preventing child abuse and neglect: A technical package for policy, norm, and programmatic activities. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Hayatbakhsh, M. R., Mamun, A. A., Najman, J. M., O'Callaghan, M. J., Bor, W., & Alati, R. (2008). Early childhood predictors of early substance use and substance use disorders: prospective study. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 42(8), 720-731.

- Long Foley, K., Altman, D., & Wolfson, M. (2004). Adults' approval and adolescents' alcohol use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 35(4), 345-e17.

- Martins SS, Segura LE, Santaella-Tenorio J, et al. Prescription opioid use disorder and heroin use among 12-34 year-olds in the United States from 2002 to 2014. Addictive Behaviors. 2017 Feb;65:236-241. DOI: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.08.033.

- Robinson, C. A., & Wilson, J. D. (2020). Management of Opioid Misuse and Opioid Use Disorders Among Youth. Pediatrics, 145, S153–S164. https://doi-org.dist.lib.usu.edu/10.1542/peds.2019-2056C

- Stein, M. D., Conti, M. T., Kenney, S., Anderson, B. J., Flori, J. N., Risi, M. M., & Bailey, G. L. (2017). Adverse childhood experience effects on opioid use initiation, injection drug use, and overdose among persons with opioid use disorder. Drug & Alcohol Dependence, 179, 325–329. https://doi-org.dist.lib.usu.edu/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.07.007

* In its programs and activities, Utah State University does not discriminate based on race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, genetic information, sexual orientation or gender identity/expression, disability, status as a protected veteran, or any other status protected by University policy or local, state, or federal law. The following individuals have been designated to handle inquiries regarding non-discrimination policies: Executive Director of the Office of Equity, Alison Adams-Perlac, alison.adams-perlac@usu.edu, Title IX Coordinator, Hilary Renshaw, hilary.renshaw@usu.edu, Old Main Rm. 161, 435-797-1266. For further information on notice of non-discrimination: U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, 303-844-5695, OCR.Denver@ed.gov. Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Kenneth L. White, Vice President for Extension and Agriculture, Utah State University.

Authors

Kandice Atismé, MHA, MPH, CPH; Jaclyn Atencio Miller, Health & Wellness Intern

Related Research