(Photo: Dr. Stoker and Scraps the Dog in Sedona, Arizona)

Spilling Over in Sedona, Arizona

By: Philip Stoker, PhD, Associate Professor in the College of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture, University of Arizona

GNAR Researcher Dr. Philip Stoker and his cute little dog, Scraps, are travelling across the Western U.S. this spring and summer for his sabbatical research into gateway communities. This new blog series – "Philip and Scraps' GNARly Adventures!" – will highlight their travels through photos and observations from gateway communities. Each post asks readers to provide insights into the challenges and their experiences in gateway communities. Please have a read and feel free to write to Philip at philipstoker@arizona.edu with any of your answers and ideas!

February 2024:

In February, Scraps and I spent a few days in the gateway community of Sedona, Arizona. I’ve made the three(ish)-hour drive from the University of Arizona in Tucson up to Sedona many times in the last few years, and have always enjoyed staying in town and camping in the surrounding red rock wilderness. I even found my new favorite spot in Sedona on this last trip: the grill next to “the most scenic airport in the U.S.” The scenery is particularly beautiful because, geologically, Sedona is located below the southern edge of the Colorado Plateau where the pine forests and red rock sandstone descend south into the Sonoran Desert. The weather was stormy in Sedona, and February is the tourist/visitation off-season (though Sedona visitation also dips when temperatures rise above 100F). Most visitors travel to Sedona for a combination of outdoor recreation, day trips from Phoenix, shopping, and health spas/resorts.

Sedona is a community facing workforce housing shortages, and impacts from visitation to the town “spill over” into nearby communities. A perfect opportunity to learn more about planning and development challenges in gateway communities.

Spillover effects

“Spillover effects” are when growth and visitation in one gateway community impact nearby communities – like tossing an orange into your cereal bowl. The impact of the orange is going to cause a lot of “spilling over” as the cereal finds somewhere else to go. In the planning context of gateway communities, these spills are housing, traffic, change in community character, and environmental degradation.

The growth in visitation to Sedona is driven by its proximity to Phoenix and its increasing national and international recognition. Sedona is only 1.5 hours away from Phoenix, which is the fourth largest metropolitan area in the US. The sprawling metropolis also has a major international airport, so visitors from around the world can fly into Phoenix and be in Sedona in under two hours. Sedona is particularly popular on Instagram, and a quick check shows that #sedona has 2.4 million posts on Instagram compared to 1.5 million for #moab and 2.2 million for #JoshuaTree. While social media may not be an exact measure of visitation and popularity, even Sedona’s community plan states: “today most people turn to social media, such as Instagram, to find out where to go, the “must-see” selfie spots, top ten sites and scenic hotspots.”

Like many other gateway communities, Sedona also experienced a boom in visitation due to the COVID pandemic. Viewed as an “escape” from the nearby major cities of the Phoenix metropolitan area, the pandemic further accelerated the community’s visibility and popularity. Estimates of tourist visitation are now above 3-million each year, with less than 10,000 year-round residents.

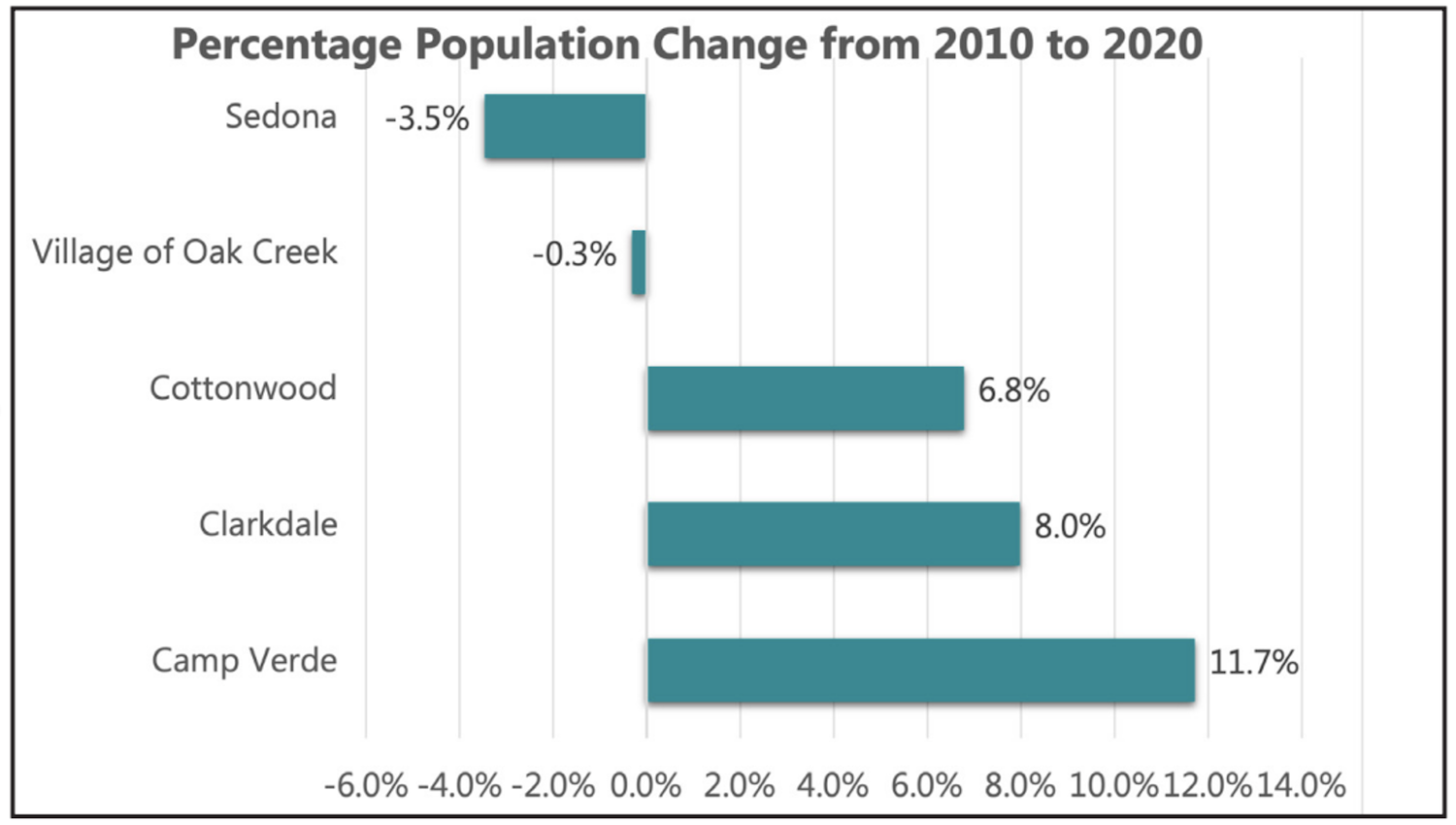

Just down the road from Sedona are the communities of Cottonwood, Camp Verde, and Clarkdale. Collectively this region is known as the Verde Valley, and these are the communities where the spillover effects from Sedona are being experienced. Despite holding their own community goals and values, these towns are becoming viewed as “the affordable housing alternative” to Sedona more and more. The figure below illustrates this trend; where Sedona’s year-round population is declining, and more and more people live in the nearby communities.

(Figure 1. Verde Valley Population Growth from Sedona’s Draft 4 Community Plan.)

So why are fewer and fewer people living in Sedona despite a boom in the tourism economy? Well, if you are reading this blog, I bet you already know… the lack of available workforce housing.

Housing in Sedona

Housing is relatively expensive in Sedona compared to other rural Arizonan communities. Their home prices are affected by the larger trends across the country (inflation and rising interest rates), but Sedona is also “landlocked” by national forest lands that limit outward growth. There isn’t a lot of “new” land for Sedona to develop, and 82% of the community is currently built-out. Sedona is a destination for both in and out-of-state retirees, and second home ownership rates are high. Their small housing stock is primarily single family, and almost 1 in 5 housing units (18%) are short-term rentals.

Short-term rentals have had negative impacts on housing affordability and community character. These impacts are felt by local residents who may be priced out of rentals and home ownership, or simply grow tired of seeing new neighbors every few days. Managing short-term rentals in Arizona is uniquely challenging compared to other states because of Arizona state law. In 2016, Arizona passed state law SB 1350, which in no uncertain language prohibits cities or counties to regulate or tax short-term rentals differently than other properties:

“A CITY OR TOWN MAY NOT PROHIBIT VACATION RENTALS OR SHORT-TERM RENTALS, RESTRICT THE USE OF VACATION RENTALS OR SHORT-TERM RENTALS OR REGULATE VACATION RENTALS OR SHORT-TERM RENTALS BASED SOLELY ON THEIR CLASSIFICATION, USE OR OCCUPANCY.”

This passage of SB1350 completely reversed Sedona’s policy towards short-term rentals, where since 1995 Sedona prohibited rentals of single-family homes for less than 30 days. By 2023, there were over 1,000 short-term rentals in the city. The law has had some amendments since 2016 to allow cities to require permits and fees to operate short-term rentals, but these amendments were mostly aimed at regulating “party houses” in the metropolitan areas. So far, Arizona legislation hasn’t considered short-term rental impacts in gateway communities. John Choi, then a spokesperson for Airbnb, said in a press statement the new law was "proof that elected officials and community stakeholders can come together to develop fair, sensible short-term rental rules that address community concerns and preserve the economic benefits of short-term rentals." Isn’t it funny that no ability to regulate at all is “fair” and “sensible” from Airbnb’s perspective?

Without regulatory power, the community has been trying to minimize the negative impacts of short-term rentals in other ways that may offer lessons for similar communities. For example, Sedona is piloting a payment system to incentivize homeowners to rent to the local workforce instead of short-term renters. The program offers between $6,000 and $10,000 a year for landlords to rent to individuals employed within the municipal boundary of Sedona. This incentive program pays homeowners 50% of the money if they can find a local worker, and then 50% after a year of renting to the worker. The city also has a deed restriction program that allows homeowners to place voluntary restrictions on their properties, to prevent their use as a short-term rental after selling the property. Finally, the community requires a fee to operate ($200) a short-term rental, and has a database of their short-term rental locations and contact information. I am interested to hear how well these programs are working, and would love to see the objective data on their effectiveness.

Other spillover effects: commuting and traffic.

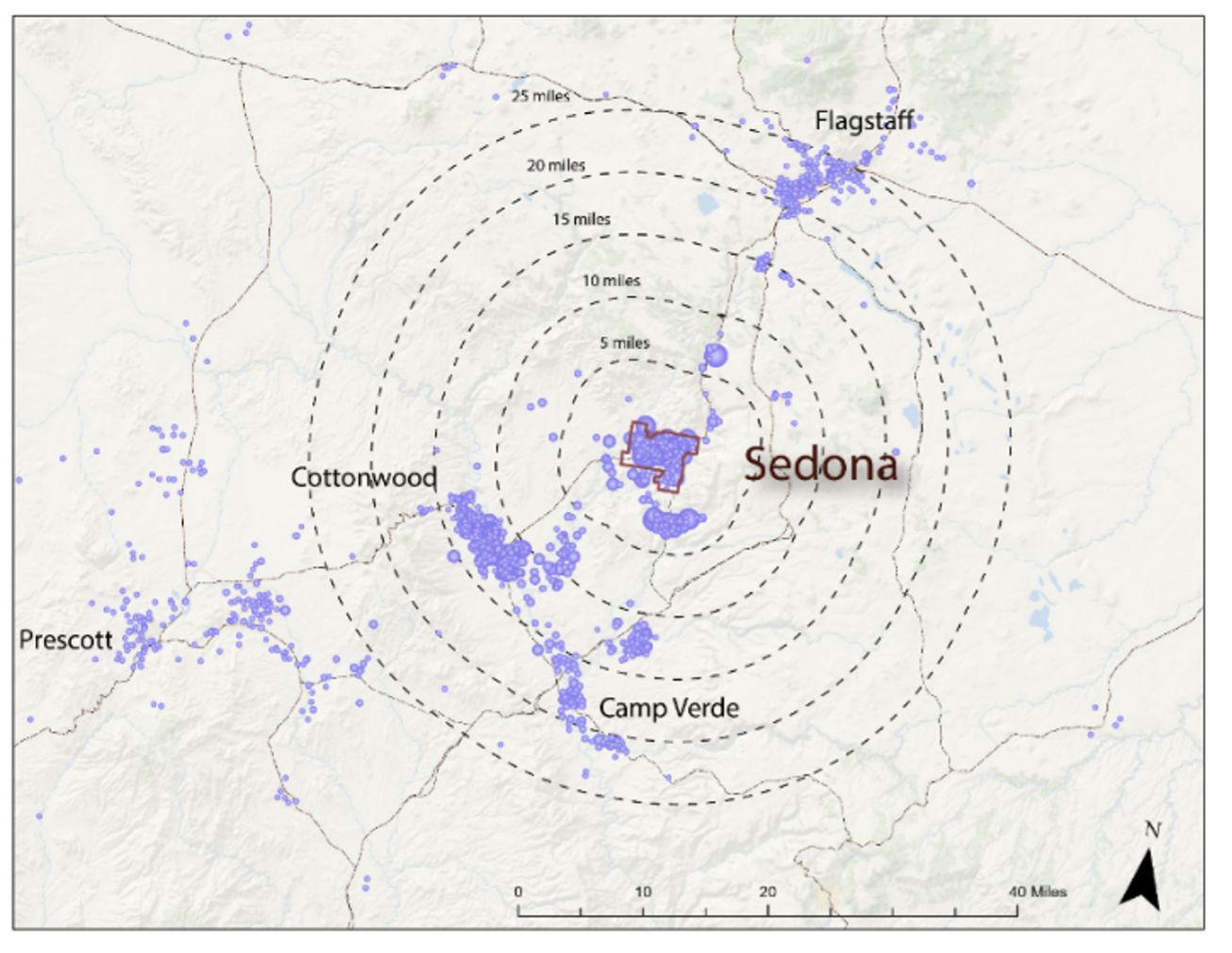

Most workers in Sedona commute to the city for their jobs while living elsewhere. This means other communities need to support and provide services for people who work in Sedona (i.e. spillover effects). U.S. census data based on unemployment filings from businesses to states (LEHD dataset) in 2021 shows that there were 6,086 employed positions in Sedona, of which 4,818 reported home addresses outside of Sedona. This means that 79% of jobs in Sedona are held by people who don’t live there. Based on the map below, it’s easy to infer how employment in Sedona causes housing and traffic pressures in nearby communities. Every purple dot represents the approximate home address of someone with a job in Sedona.

(Figure 2. Sedona's estimated commutershed. Source: Philip Stoker)

To drive that point home (pun intended), our AirBnB host lived about 20 minutes down the road in Cottonwood, AZ.

(As a brief aside, if you are interested in working with this data and making similar maps, see this GNARLY blog entry from a few years ago for instructions.)

During peak season, there are some awful traffic conditions in Sedona. The surges in visitation and a unique street layout separating the three main districts of Sedona can cause substantial congestion for a rural town. In the center of Sedona, there are a series of traffic roundabouts that everyone must pass through, and the traffic can back up for miles turning a ten-minute drive into an hour hold-up. It was apparent while walking and driving around Sedona during this visit that the community has been working hard to try and accommodate visitation from a transportation perspective.

Sedona has implemented several transportation strategies from their recently adopted transportation master plan. There is a shuttle service between trailheads and different parts of the community, which operates more frequently during peak visitation. The road network includes many roundabouts (although locals report tourists don’t know how to use them), and parking at trails often requires paid parking through permits (i.e. Red Rock Access Pass). Signage was clear and consistent for public parking, and the highways into and out of Sedona are two to four lanes with bike lanes and sidewalks.

When overcrowded trailhead parking impacts residents, people seem to have no problem making their own signs (as seen in the photo below).

(Figure 3. A homemade "no parking sign" near to an often busy trailhead. Source: Philip Stoker)

(Figure 3. A homemade "no parking sign" near to an often busy trailhead. Source: Philip Stoker)

But even with successful implementation of these strategies, how is the traffic ever going to decrease short of a drop in visitation? I wonder if comparable investments have been made, or are even feasible, in the other Verde Valley communities. Are the investments in transportation funded by the economic activity of the tourists to Sedona?

We should learn more from Sedona and the Verde Valley.

When we conducted our first survey of public officials working in Gateway Communities in 2018, we received three responses from Sedona. There was consensus among the public officials that housing, crowding, and transportation were the primary challenges. We didn’t get any responses in our 2021 survey from Sedona, but I would guess the challenges are only more severe right now.

In a far less rigorous and valid methodology, a scan of reddit users on r/Sedona represented some local opinions on these related issues. One comment that captured many sentiments was: “I'd much rather visit and live within an hour than live in it again.” As this quote captures nicely, no one has complaints about the scenic beauty of Sedona, and this is a very special place for many people. However, they have problems with affordability, housing, transportation, and crowds. Can Sedona and the Verde Valley harness the economic benefits of a strong tourism economy to implement strategies to address housing and transportation challenges?

I’ll be back to visit Sedona soon and definitely have more to learn about these communities and regions. But for now, I think there is a question that all gateway communities need to consider: who is this town for?

Is this a town that is meant for tourists, or a town that people come to visit as tourists? As of now, Sedona seems to be leaning towards a town run for the benefit of tourists. The economic benefits are great and are likely funding many of the improvements we saw around Sedona, however this focus on just one part of the economy may become a common “tipping point” for gateway communities. If the ratio of benefits for tourists outweighs the benefits for residents too much, the town will be fundamentally changed.

Hopefully through good planning and maybe some luck, Sedona and the Verde Valley can protect what makes them such wonderful places.

If you know more about planning and development in the Verde Valley, I’d love to hear from you! Feel free to write to me at philipstoker@arizona.edu. If you don’t write to me, that’s ok… I just might be visiting your gateway community next and I’ll be asking then. Look out for me and this little dog!

Philip Stoker, PhD, is an assistant professor of planning and landscape architecture in University of Arizona's College of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture. Philip holds a Ph.D. in Metropolitan Planning, Policy, and Design from the University of Utah where he completed his thesis on urban water use and sustainability. His academic foundations are in ecology, planning, and natural resource management. He has conducted environmental and social science research internationally, including work with the World Health Organization, Parks Canada, the National Park Service and the Vancouver 2010 Olympic Games.

Philip has expertise in urban water demand and the integration of land use planning with water management. His research on urban water demand has focused on how land cover, built environmental characteristics, social conditions, and demographics all interact to influence water use in Western U.S. cities.