Exercise and Chronic Pain

Chronic pain is perhaps the most pervasive medical issue in the United States (US). The long-term impacts of chronic pain often cause individuals to reduce or eliminate physical activity. Chronic pain is generally defined as any pain that lasts longer than three to six months (treede, et al., 2015). It is estimated that around 20% of adults in the U.S. experience chronic pain with an additional 8% of adults experiencing frequent, and at times, debilitating, chronic pain (Geneen, et al., 2017). In fact, chronic pain is the most common reason adults see medical treatment in the United States (Greneen, et al., 2017). Chronic pain can impact physical, mental, and emotional well-being, which can limit daily activity and quality of life. This impact on willbeing ranges in severity from moderate to severe (Dueñas, et al., 2016; Geneen, et al., 2017). The purpose of this fact sheet is to address the common barriers to being physically active with chronic pain and provide suggestions for safe ways to be physically active even when chronic pain is present.

How Chronic Pain Impacts Activity

Pain interference is one of the ways pain is measured because of the way pain interferes with normal daily activity. Chronic pain conditions can seriously affect daily activities and quality of life (Amtmann, et al., 2010; Dueñas, et al., 2016). Some of the ways pain has been shown to limit activity include (Björnsdóttir, et al, 2013; Henschke, et al., 2021):

- unable to carry groceries

- unable to climb stairs

- unable to stand up straight

- not enough energy by end of day

- having to take rest breaks or stop activity

- missing school or work

- withdrawing from social activity

One study in the UK found that approximately 70% of all neck pain moderately to severely limited the amount and types of daily activity (Thomas, et al., 2004). To make matters worse, mental health has generally been found to decline as pain intensifies (Gilmour, 2015).

In the past, pain assessments focused solely on pain intensity and location. Doctors now recognize that to fully understand the impact of pain, researchers need to measure the emotional and behaviroal impacts and how pain interferes with physical functioning (Breivik, et al., 2008).

How the Body & Mind Respond to Pain

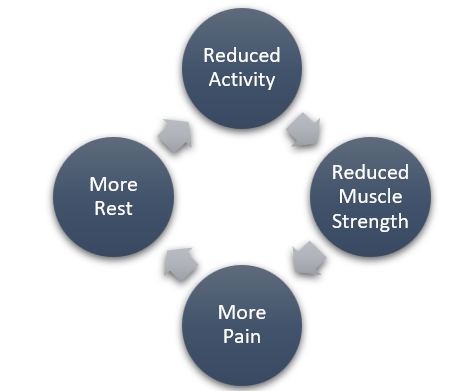

When an individual suffers from chronic pain, the natural response is to do anything to reduce it. For many, that instinct is to rest and relax. This can lead to a vicious cycle of self-limiting activity (Grady & Gough, 2014).

Figure 1. Self-Limiting Cycle (Grady & Gough, 2014) Too much rest can be detrimental and result in atrophy (or wasting) of the muscles (Loos, et al., n.d.). This may lead to other health problems including poor posture, less joint stability, and other structural problems (Loos, et al., n.d.).

Too much rest can be detrimental and result in atrophy (or wasting) of the muscles (Loos, et al., n.d.). This may lead to other health problems including poor posture, less joint stability, and other structural problems (Loos, et al., n.d.).

The reasons we may limit physical activity is easy to understand using the ‘fear-avoidance’ model of pain. We avoid activity because we fear injury or the pain from the movement. When we stop, rest, or avoid movement we feel less afraid, and that sense of relief reinforces the decision to stop the activity, but this cycle eventually increases the level of disability and distress (Mackichan, et al., 2013). Activity restriction can become so limiting that many chronic pain sufferers feel their independence is threatened because of their pain (Mackichan, et al., 2013). While these reactions are understandable, all of the evidence points toward the benefits of physical activity in managing pain.

Benefits of Activity for Chronic Pain

There are many general health benefits to physical activity that have been studied, including boosts to brain health, weight management, reduced disease burden, and stronger bones and muscles (Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), n.d.). The CDC even notes that maintaining a physically active lifestyle reduces the risk of developing chronic diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, some forms of cancer, and other obesity-related illnesses. Physical activity can lower the risk for developing chronic pain, as well as assist in managing existing chronic pain (Law, et al., 2017). There are a number of benefits of physical activity and exercise for individuals suffering from chronic pain. Physical activity has been shown to reduce chronic pain by building muscle strength and flexibility, reducing fatigue, reducing pain sensitivity and reducing inflammation. Research suggests that exercise may even be effective in reducing pain for difficult-to-treat conditions like fibromyalgia and neck/shoulder pain (Belavy, et al., 2021). Below is a list of additional benefits of physical activity among individuals experiencing chronic pain.

Builds Muscle Strength. Physical activity can help prevent muscular atrophy, which then can decrease pain by strengthening the muscles and improving flexibility (Law, et al., 2017).

Reduces Fatigue. Physical activity has been shown to reduce fatigue, a common symptom in many chronic pain conditions (Rall, et al., 2011).

Improves Sleep. A meta-analysis of high-quality research indicated significant improvements in sleep quality (Ambrose & Golightly, 2015).

Reduces Pain Sensitivity. Some research has found that exercise may be effective for reducing pain sensitivity when compared to non-exercise training treatments (Belavy, et al., 2021). Exercise can change how the brain responds to pain by normalizing the pain signal process and promoting the release of analgesics, such as natural pain relievers and serotonin, that turn off pain signals. (Law, et al., 2017)

Reduces Inflammation. Muscles can release chemicals that prevent pain signals from going to your brain, and the immune system increases anti-inflammatory cytokines that promote tissue healing (Exercise to Treat Chronic Pain, 2018).

Reduces depression, anxiety, and improves mood. With 80-90% of chronic pain sufferers experiencing mood disruption as a result of their pain, this benefit of physical activity is worth taking a second look (Ambrose & Golightly, 2015).

The CDC has produced a chart that lists multiple health benefits of physical activity: https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/adults/pdfs/Health_Benefits_PA_Adults_Jan2021_H.pdf

Is Physical Activity Right for Me?

Recent research recommends that because physical movement is so important in improving chronic pain, it should be prescribed to patients, similar to how medications are prescribed (Sanchis-Gomar, et al., 2021). Both aerobic and strengthening exercises can help reduce or manage pain. The important thing is to keep moving. When determining the best exercise for you, choose the exercise that you enjoy. This will help you continue to be active.

Doctors have not come to a consensus on how much exercise to recommend based on different chronic pain conditions. The general recommendation is that movement, no matter how minimal, is desirable. Added to this are four precautions that can make exercise safe for almost any condition; 1) modify to reduce risk of falls, 2) ensure proper posture, 3) use a range of motion that doesn’t increase pain, and 4) use a “start low, go slow” approach (Ambrose & Golightly, 2015).

A healthcare professional can review your current health status, activity level, and prior health-related events, using the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) (Harvard Medical School, 2012). This tool can help assess your readiness to engage in physical activity (Warburton, et al., 2011; Bredin, et al., 2013). The most updated 2017 version can be found at: https://store.csep.ca/pages/getactivequestionnaire (Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology, 2021).

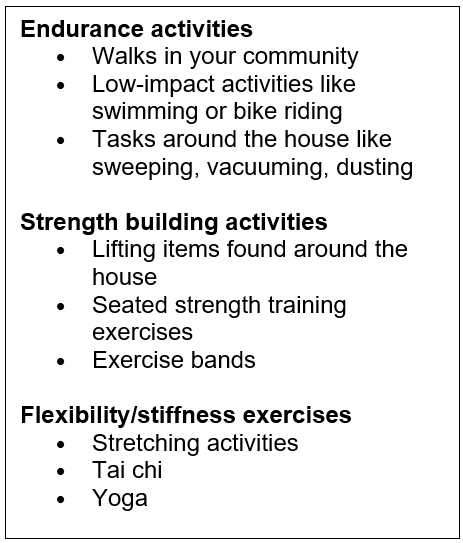

Despite these many benefits of physical activity, it can still feel overwhelming to contemplate increasing physical activity when suffering from chronic pain. It is important to note that being physically active does not have to involve a gym membership, formal exercise classes, or vigorous intensity activities. Engaging in any activities that result in moving more and sitting less will lead to the desired health benefits and possibly help manage or reduce your chronic pain (Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), 2018). Some activities that might work well for individuals with chronic pain include:

Figure 2. Activities with Chronic Pain

While being physically active can lead to overall health benefits and management of chronic pain, pacing is important to avoid overdoing it (Grady & Gough, 2014). The vicious cycle of over-doing begins as a person begins to recover, feels better, then pushes too hard, resulting in more pain and eventual collapse and a longer recovery. As you contemplate whether to increase your activity, keep these things in mind to avoid pushing your body too hard:

- When being physically active, do not ignore worsening pain. Ignoring pain can exacerbate pain conditions and possibly lead to inflammation.

- Avoid pushing your body too hard on days where your chronic pain is less intense. Even though you may be feeling better, it is still important to not overdo it.

- If pain, swelling, or inflammation is present in a specific joint or area of the body, focus on a different area.

- If pain is increasing, or something does not feel right in your body, seek advice and support from your medical team. (National Institutes on Aging, n.d)

How to Get Started

If you haven’t been active before, or are becoming active again after a long break, consider these tips as you make a plan:

- Always consult with a physician or medical professional about starting or re-engaging in activity.

- Don’t let the guidelines get you down. Although the general physical activity recommendations for adults is 30 minutes per day, five days per week (totaling 150 minutes), studies show that breaking up exercise sessions into 10-minute chunks has similar health benefits (Harvard Medical School, 2018). Research has shown that moderate activity just 2-3 times a week reduces pain and depression (Ambrose & Golightly, 2015)

- Physical activity includes any activity that increases movement and decreases sedentary time, including routine activities, chores, and hobbies. The CDC offers practical suggestions for incorporating physical activity daily:

- Dedicate time to make activity part of the day, and consider it an appointment, just like a doctor’s appointment.

- Consider activities, locations, and times that are enjoyable and motivating.

- Engage your family and/or friends to act as motivators for one another.

- Start slowly and work up to more challenging activities. Rushing into an activity can lead to soreness, fatigue, injury, and loss of motivation to continue.

- Break up bouts of sitting by standing and doing activities, such as marching during TV commercials, walking around the office, and walking up and down stairs (Harvard Health Publishing, 2014.

- Breaking up sitting with activities is shown to improve glucose levels, insulin response (Dunstan, et al., 2012), resting blood pressure (Larsen, et al., 2014), fatigue, and musculoskeletal discomfort (Thorp, et al., 2014).

(Adapted from CDC, 2021)

- Consider any potential costs of starting a physical activity program and choose options within your budget.

- If classes are too strenuous, consider asking to join during the warm-up or cool-down time periods only.

- The internet, TV and other online resources may also be good places to find physical activity routines.

- Use trial periods and local programs to increase options:

- Take advantage of free trial periods and multiple facilities, taking note of the quality of the equipment, safety, trained staff, hours, busy times, etc. (American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM), 2019).

- Watch out for fees and promotional periods that may be incorporated into membership plans and negotiate for better terms (ACSM, 2019; American Council on Exercise (ACE), 2009a).

- Utilize free sessions with a personal trainer that may be offered with gym or facility memberships and ask additional questions to learn about equipment and the trainer to determine whether the relationship is a good fit (ACE, 2009b).

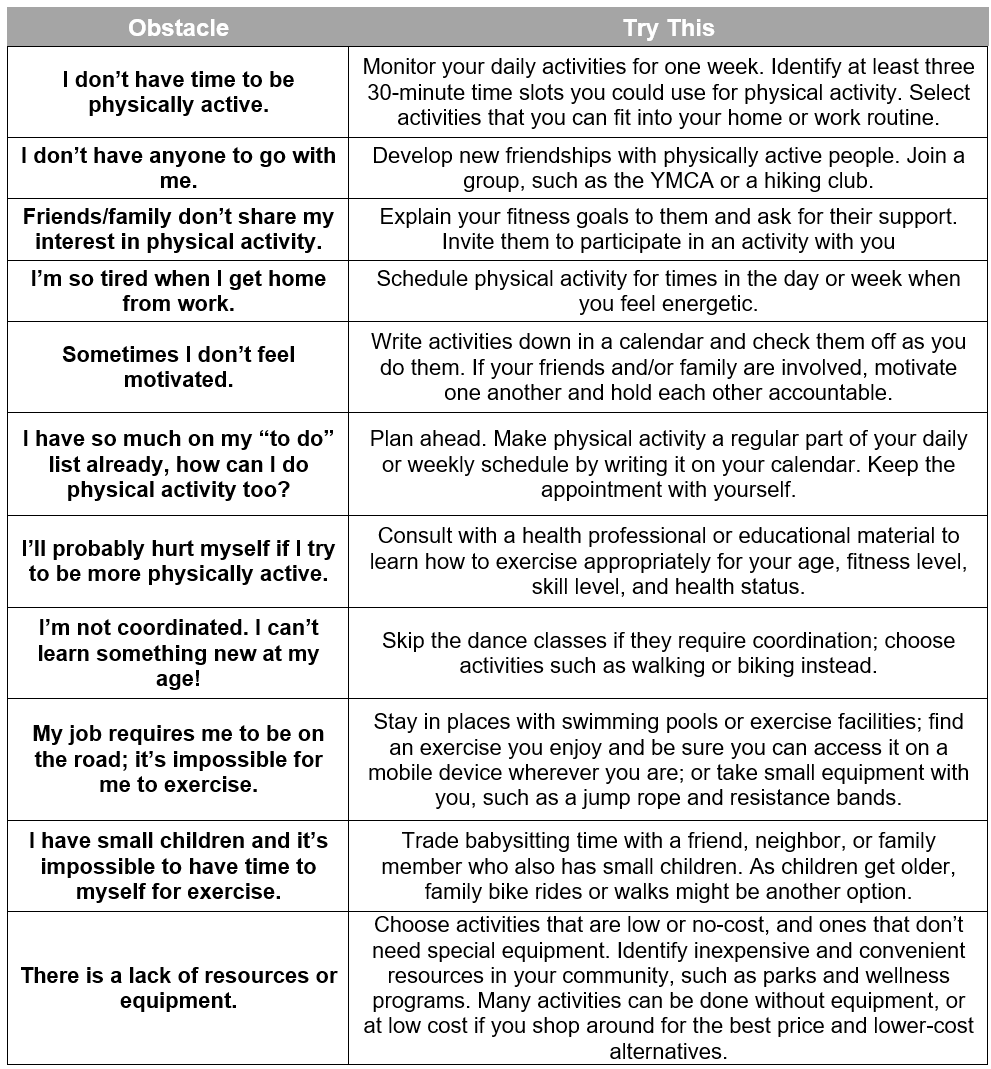

Overcoming Barriers

Barriers are inevitable, so planning ahead can help create alternative options for any expected and unexpected situation that arise. Common barriers experienced by individuals experiencing chronic pain are the pain itself, poor sleep, depression, anxiety, fear-avoidance beliefs, and feeling unsure about how to start and whether success is possible (Ambrose & Golightly, 2015). Additionally, fear for safety and worry about additional injury can add to the fear-avoidance cycle. Talking to a healthcare professional can help alleviate these concerns. In addition, the table below lists common worries and barriers along with suggestions for overcoming them.

Summary

In summary, chronic pain takes a major toll on health in the US. One of the ways that happens is when fear of pain and injury prevent individuals with chronic pain from engaging in activity. Studies suggest that physical activity can be safe for people who suffer from chronic pain and can actually reduce the pain that is experienced long-term. It is important to be careful, consult experts on safety, and pace the activity in a way that avoids over-doing. Following the

simple guidelines and suggestions in this fact sheet can lead to greater confidence in movement and reduced pain for chronic pain sufferers.

Table 1. Common Barriers & Suggested Responses, Adapted from: CDC, 2021 and American Heart Association, 2019

References

- Ambrose, K. R., & Golightly, Y. M. (2015). Physical exercise as non-pharmacological treatment of chronic pain: Why and when. Best practice & research. Clinical rheumatology, 29(1), 120–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2015.04.022

- American College of Sports Medicine (2019). Selecting the Right Fitness Facility for You. Retrieved April 22, 2021, from: https://www.acsm.org/docs/default-source/files-for-resource-library/selecting-the-right-fitness-facility.pdf?sfvrsn=234d6f96_4

- American Council on Exercise (2009a). How to Choose a Health Club. Retrieved April 22, 2021, from: https://www.acefitness.org/education-and-resources/lifestyle/blog/6620/how-to-choose-a-health-club/

- American Council on Exercise (2009b). How to Choose the Right Personal Trainer. Retrieved April 22, 2021, from: https://www.acefitness.org/education-and-resources/lifestyle/blog/6624/how-to-choose-the-right-personal-trainer/

- American Heart Association (2018). Breaking Down Barriers to Fitness. Retrieved April 22, 2021, from: https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/fitness/getting-active/breaking-down-barriers-to-fitness

- Amtmann, D., et al. (2010, Jul). Development of a PROMIS item bank to measure pain interference. Pain, 150(1), 173-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.025

- Belavy, D. L., Van Oosterwijck, J., Clarkson, M., Dhondt, E., Mundell, N. L., Miller, C. T., & Owen, P. J. (2021). Pain sensitivity is reduced by exercise training: Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 120, 100–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.11.012

- Björnsdóttir, S. V., Jónsson, S. H., & Valdimarsdóttir, U. A. (2013). Functional limitations and physical symptoms of individuals with chronic pain. Scandinavian journal of rheumatology, 42(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.3109/03009742.2012.697916

- Bredin, S. S., Gledhill, N., Jamnik, V. K., & Warburton, D. E. (2013). PAR-Q+ and ePARmed-X+: new risk stratification and physical activity clearance strategy for physicians and patients alike (2013). Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien, 59(3), 273–277.

- Breivik, H., Borchgrevink, P. C., Allen, S. M., Rosseland, L. A., Romundstad, L., Hals, E. K., Kvarstein, G., & Stubhaug, A. (2008). Assessment of pain. British journal of anaesthesia, 101(1), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aen103

- Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology (2021). Pre-Screening for Physical Activity: Get Active Questionnaire. Retrieved at: https://store.csep.ca/pages/getactivequestionnaire

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021). Should I take precautions before becoming more active? Retrieved April 22, 2021, from: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/physical_activity/getting_started.html

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Benefits of physical activity. Retrieved April 22, 2021, from:

https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/pa-health/index.htm - David W. Dunstan, Bronwyn A. Kingwell, Robyn Larsen, Genevieve N. Healy, Ester Cerin, Marc T. Hamilton, Jonathan E. Shaw, David A. Bertovic, Paul Z. Zimmet, Jo Salmon, Neville Owen (2012). Breaking Up Prolonged Sitting Reduces Postprandial Glucose and Insulin Responses. Diabetes Care, 35(5), 976-983; DOI: 10.2337/dc11-1931

- Dueñas, M., Ojeda, B., Salazar, A., Mico, J. A., & Failde, I. (2016). A review of chronic pain impact on patients, their social environment and the health care system. Journal of pain research, 9, 457–467. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S105892

- Dunstan, D.W., Kingwell, B.A., Larsen, R., Healy, G.N., Cerin, E., Hamilton, M.T., Shaw, J.E., Bertovic, D.A.,

Gilmour H. (2015). Chronic pain, activity restriction and flourishing mental health. Health reports, 26(1), 15–22. - Geneen, L., Moore, R., Clark, C., Martin D., Colvin, L., Smith, B. (2017). Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: An overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011279.pub3

- Grady, P. A., & Gough, L. L. (2014). Self-management: a comprehensive approach to management of chronic conditions. American journal of public health, 104(8), e25-e31. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302041

- Harvard Medical School (2012). Do you need to see a doctor before starting your exercise program? Harvard Health Publishing Healthbeat. Retrieved April 22, 2021, from: https://www.health.harvard.edu/healthbeat/do-you-need-to-see-a-doctor-before-starting-your-exercise-program

- Harvard Health Publishing (2014). Get on your feet: 8 creative ways to avoid too much sitting. Harvard Women’s Health Watch. Retrieved April 22, 2021, from: https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/get-on-your-feet-8-creative-ways-to-avoid-too-much-sitting-

- Harvard Medical School (2018). Rethinking the 30-minute workout. Harvard Health Publishing Harvard Men’s Health Watch. Retrieved April 22, 2021, from: https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/rethinking-the-30-minute-workout

- Henschke, N., Kamper, S. J., & Maher, C. G. (2015, January). The epidemiology and economic consequences of pain. In Mayo Clinic Proceedings (Vol. 90, No. 1, pp. 139-147). Elsevier.

- Larsen, R., Kingwell, B., Sethi, P., Cerin, E., Owen, N., & Dunstan, D. (2014). Breaking up prolonged sitting reduces resting blood pressure in overweight/obese adults. Nutrition, Metabolism, and Cardiovascular Diseases, 24(9), 976-982. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2014.04.011

- Law, L. F., & Sluka, K. A. (2017). How does physical activity modulate pain?. Pain, 158(3), 369–370. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000792

- Loos, H., Sulzer, S. H., & Atisme, K. (n.d.). Exercise Tips for Chronic Pain Management. Utah State University Extension. Retrieved March 13, 2021, from https://extension.usu.edu/heart/files/exercisetipsforchronicpainmanagement.pdf

- Mackichan, F., Adamson, J., & Gooberman-Hill, R. (2013). 'Living within your limits': activity restriction in older people experiencing chronic pain. Age and ageing, 42(6), 702–708. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/aft119

- National Institute on Aging. (n.d.) Exercising with Chronic Conditions. Retrieved March 13, 2021, from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/exercising-chronic-conditions

- Rall, L. C., & Roubenoff, R. (2011). Benefits of Exercise for Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Nutrition in Clinical Care, 3(4), 209-215. Exercise as a treatment for chronic low back pain. The Spine Journal, 4(1), 106-115.

- Thomas, E., Peat, G., Harris, L., Wilkie, R., & Croft, P. R. (2004). The prevalence of pain and pain interference in a general population of older adults: cross-sectional findings from the North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Project (NorStOP). Pain, 110(1-2), 361–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2004.04.017

- Thorp, A., Kingwell, B., Owen, N., & Dunstan, D. (2014). Breaking up workplace sitting time with intermittent standing bouts improves fatigue and musculoskeletal discomfort in overweight/obese office workers. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 71(11), 765-771. DOI: 10.1136/oemed-2014-102348

- Treede, R.-D., et al. (2015). A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain, 156(6), 1003-1007. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000160

- University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. (2018, March). Exercise to treat chronic pain. [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved April 01, 2021, from: https://uihc.org/health-topics/exercise-treat-chronic-pain

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2018). Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition. Washington, D.C.

- Vina J, Sanchis‐Gomar F, Martinez‐Bello V, & Gomez‐Cabrera MC. (2021). Exercise acts as a drug; the pharmacological benefits of exercise. British journal of pharmacology. 2012 Sep 1;167(1):1-2.

- Warburton, Darren E.R., Jamnik, Veronica K., Bredin, Shannon S.D., McKenzie, Don C., Stone, James, Shephard, Roy J., and Gledhill, Norman (2011). Evidence-based risk assessment and recommendations for physical activity clearance: an introduction. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism. 36(S1): S1-S2. https://doi.org/10.1139/h11-060

- Zimmet, P.Z., Salmon, J., Owen, N. (2012). Breaking Up Prolonged Sitting Reduces Postprandial Glucose and Insulin Responses. Diabetes Care, 35(5), 976-983; DOI: 10.2337/dc11-1931

Authors

Maren Wright Voss, ScD; Mateja Savoie-Roskos, PhD; Casey Coombs, MS; Gabriela Murza, MS; Cindy Nelson, MS; Elise Whithers, BS

Related Research