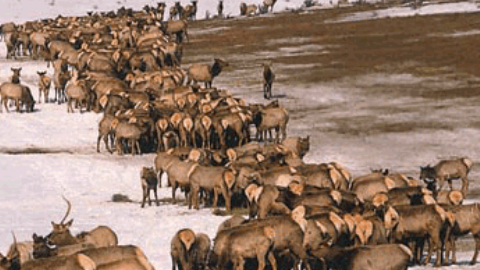

Wintering Elk

Please Don't Feed the Elk: An Applied Management Experiment

Wildlife managers have fed elk in North America for nearly 100 years. Feeding elk in winter compensates for a shortage of natural winter range, may boost elk populations, aid in preventing commingling with livestock and reduce depredation of feed intended for livestock. Unfortunately, there are economic and environmental costs associated with feeding elk. Futhermoe, elk herds wintering on feeding grounds have a higher risk of contracting and transmitting disease due to high animal densities. Brucellosis is of primary concern now, and Chronic Wasting Disease may be in the future. Discontinuing winter-feeding programs may be necessary to decrease disease spread.

Funded by the Division of Wildlife Services, USU graduate student, Dax Mangus, evaluated the use of behavioral training to reduce winter-feeding of elk, while maintaining elk populations and reducing human-wildlife conflicts. The study was conducted at Deseret Land & Livestock (DLL) in Rich County, UT under the direction of Dr. Fred Provenza and DLL wildlife manager, Rick Danvir. Managers at DLL have over 20 years of data on elk feeding during winters. Dax tested the effectiveness of: 1) range improvements, 2) strategic cattle grazing, 3) dispersed supplemental feeding, 4) hunting, and 5) herding as tools to distribute and hold elk in desired areas during winter. He compared elk numbers on feeding grounds at DLL during this study with historic data from DLL, as well as other comparable feed sites in Wyoming.

To train elk to avoid certain areas of the ranch, hunters targeted elk in designated shoot zone, especially elk lingering near the historic feeding grounds. The intent was to punish elk eager to receive winter feed, and motivate them to search for food elsewhere. Herding was used whenever elk approached roads, were eating stored hay outside the ranch boundaries or when hunting season was over. To encourage elk to stay in the safe zone at the ranch, no hunting or herding was allowed, range improvements and strategic cattle grazing improve the quantity and quality of the forage in the safe zone. Dax also tried supplementation in the form of low-moisture blocks (LMB) to keep elk in the safe zone, but despite the fact elk would consume granular and liquid molasses they would not consume LMB during the study.

To train elk to avoid certain areas of the ranch, hunters targeted elk in designated shoot zone, especially elk lingering near the historic feeding grounds. The intent was to punish elk eager to receive winter feed, and motivate them to search for food elsewhere. Herding was used whenever elk approached roads, were eating stored hay outside the ranch boundaries or when hunting season was over. To encourage elk to stay in the safe zone at the ranch, no hunting or herding was allowed, range improvements and strategic cattle grazing improve the quantity and quality of the forage in the safe zone. Dax also tried supplementation in the form of low-moisture blocks (LMB) to keep elk in the safe zone, but despite the fact elk would consume granular and liquid molasses they would not consume LMB during the study.

The first two winters of the study were mild. Elk feeding was eliminated and they stayed on the ranch. The final winter of the study was severe, but both quantity and duration of feeding were reduced. Since the conclusion of Dax’s study, DLL has further reduced quantity and duration of feeding elk during severe winters, and has completely eliminated feeding in mild winters. Based on a Before After Control Impact (BACI) analysis, the reduction in the proportion of the elk population fed at DLL was significantly less than the proportion of the elk populations fed at the control sites in Wyoming (P=0.057).

Dax was unable to separate the contribution of each method to dispersing and holding elk in desired locations. However, wildlife managers can likely decrease dependence on costly supplemental winter-feeding, reduce the risks of disease and hay depredation, and keep human-wildlife conflicts at a minimum by using a combination of methods used in this study. For more information read Dax's Thesis.