Maximizing Quality of Life for Persons with Dementia

When loved ones develop Alzheimer’s disease or another kind of dementia, spouses and other family members often assist with daily needs, like driving, shopping, and eventually even personal care (feeding, bathing, and dressing). Family care arrangements and formal care plans within an assisted living facility or nursing home often focus around meeting the physical and practical needs of the patient.

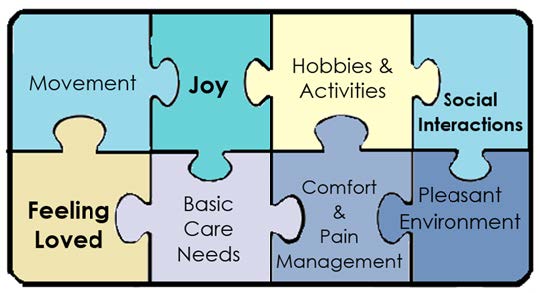

In the last 20 years or so, research strongly supports that an even higher quality of life can be reached by persons with dementia, with some help from their paid or family caregivers. While having basic care and supervision is essential for someone with dementia, it is only one piece of the puzzle in providing them with a high quality of life.

People without dementia require more than basic needs to lead a holistic and fulfilling life. We need social interactions, emotional connections, enjoyable activities, and so on. These same psychological and social needs exist for someone experiencing dementia (Kitwood, 1997), although the ways to participate in those experiences may need modification.

(adapted from Brod et al., 1999)

When trying to maximize quality of life for people with dementia, researchers have identified key areas for caregivers to focus on (Brod, Stewart, Sands, & Walton, 1999). Most family and paid caregivers recognize that Basic Care Needs and Comfort and Pain Management are essential pieces of their role - it is clear that they need to care for the person with dementia’s physical needs. It is the remaining six categories that are sometimes overlooked, but which are also important in contributing to the psychological well-being of the patient.

We emphasize that caregiving for someone with dementia can be stressful, and we do not imply that caregivers need to provide everything in the puzzle below. In addition to the round-the-clock supervision, answering questions that are asked over and over, providing the physical care, and managing the emotional stress of maintaining a relationship with someone who may not be able to reciprocate the affection, we don’t mean to imply that caregivers need to do “even more.” Caregivers need care, too, and should rely on their network of friends and family members to help with some of these activities below. Many of these activities, when done together with the person with dementia, can build quality of life for the caregiver, too. Taking walks, enjoying a pretty environment, smiling and finding joy together – these are good for both the person receiving care and the caregiver.

Basic Care Needs

Caregivers are responsible for making sure a person with dementia has nutritious food, hydration, and basic personal care – bathing, dressing and toileting. Caregivers are also responsible for making sure they received their proper medical care, and get them to and from doctor’s appointments.

Comfort and Pain Management

Caregivers are responsible for making sure the patient’s medical needs are addressed. People with dementia cannot always articulate that they are in pain, or exactly what kind of pain they are feeling. Caregivers can look for cues such as not using an arm or other body part, grimacing, not wanting to eat (because of dental pain), or other overall signs of distress.

Movement

Just because a person has lost his or her ability to do mental tasks, does not mean he or she has lost the desire to move and be physically active. People with dementia sometimes appear agitated, or “pent up,” which may be an indicator that they need to get out into a new environment, and/or expend some energy. If they are hovering near a door, chances are, in their mind they have a need to go somewhere. Even if caregivers cannot take them to the place they want to get to, agitation can be reduced by getting them out for some exercise.

Going for a supervised walk outdoors with the person with dementia is a great activity. It exposes the person to a new and stimulating environment; it is a “remembered” activity that does not require rules or complex processing, it is often a good way to get rid of energy, which can promote a better night’s sleep, and it is a fun shared activity – good for the caregiver too. Even people in wheelchairs can benefit from an outdoor excursion – the change in environment can be refreshing. Never send a person with dementia out for a walk on their own, even if they tell you they remember where they are going. This should always be a supervised activity. In bad weather, consider accompanying them to an exercise class for seniors – they are often free at local senior centers.

Hobbies and Activities

People without dementia get bored and restless if they don’t have something to do. While a person with dementia is often no longer capable of participating in activities they enjoyed years before, there are simple ways to provide stimulating activities, particularly in areas they once enjoyed.

- A person with dementia who was a wood worker may enjoy rubbing some sandpaper on wood – this is a familiar activity and there does not need to be an end-product – just the process may give them something enjoyable to do.

- A person who used to garden may enjoy sitting at a table and repotting plants or planting seeds. Again, even if the caregiver never does anything with the seeds and soil, this can be a great way for the person with dementia to spend some time doing what they love, and what feels familiar.

- Feeling active is not limited to leisure timeactivities – people with dementia also feel useful doing familiar tasks. Have a basket of towels for them to fold (and no need to correct them if they are folded incorrectly). Have them knead some dough, set the table, or wipe off counters.

- Music is a very meaningful activity for people with dementia – they can shake a maraca to the beat of an old song – they may even remember lyrics to songs from their teenage years – put the songs on and sing, and invite them to dance.

Social Interactions

Research from Utah State University shows that positive social interactions elicit positive responses in people with dementia. Even in people with moderate-to-advanced dementia and who had limited language ability, researchers observed nodding, smiling, or other signs of positive engagement, following a positive interaction. People with dementia may not know who the person greeting them is, but research shows they can often still recognize social cues. In their state of confusion, we can imagine them thinking “this person seems friendly” or “even if I don’t know who this person is, they seem nice.”

Conversations with a person with dementia do not have to make sense to the caregiver, but even the nonsensical conversations can still engage and benefit the person with dementia. Sometimes the person needs a prompt:

- Ask them to tell you about their wedding day, or ask them where they like to go on vacation. Long-term memories are preserved, much more so, than short-term memories.

- Ask them if they have any plans for the weekend (even if you know that they don’t, they can still talk about what they think may be happening – again these narratives don’t have to be accurate).

The main rule for discussion with people with dementia, is that the facts do not have to make sense. They do not have to answer your question, exactly, but you can still engage the person in a friendly chat that helps fulfill his or her need for positive social interaction.

Pleasant Environment

Environments that do not have enough stimulation may be boring to an active person with dementia, but research also shows that noisy or complicated environments can be overwhelming or overstimulating to a person with dementia. People with dementia seem to appreciate calm and pleasing environments – relaxing and pretty places may be unfamiliar, but send the signal to them in their confused state, that the place is safe and good.

Feeling Loved

Smiling, acts of kindness, complementing the person with dementia, and holding their hand, are often well-received by the person with dementia. Family members can still hug and cuddle with the person. Read the following scenario:

- An older woman with dementia, named Angela, is confused – she thinks that her son, Steven, is really her own brother (whose name was Frank). Angela seems unaware that Frank has been dead for several years, and keeps calling Steven by the name Frank. Angela seems happy to see the person she thinks is Frank.

- What can her son, Steven, do in this scenario?

- It doesn’t help to tell Angela that Frank is dead – that will confuse her further and it may make her very sad or angry. What good does it do to convince her of that reality, in this moment?

- What if Steven still hugged his mother and told her he loved her? It doesn’t matter if the name she is calling him is wrong. The love is real. The two can spend some quality time together, even if the facts are not completely correct.

- The point is not to re-establish the “old” relationship. Angela has brain damage and she may not be capable of understanding that Steven is her son. Instead of re-creating “what once was,” the goal can be to maximize “what is now.” There is still love, and it may need to be expressed differently, but it can still be a meaningful exchange for both Steven and Angela.

Joy

A person with dementia can still experience basic emotions, including happiness. When others in the room are smiling and having fun, they read the social cues and understand that this is a happy and welcoming place. Doing a twirl or a little dance will often make a person with dementia laugh – they recognize that this person in the room with them is being silly or having a good time.

Ask them about places they love, and things that make them feel happy. Again, their facts and stories might not make sense, but often they will smile or laugh while telling the stories. Small moments of joy, even in the face of a debilitating disease, are reminders that this person can still experience quality in their life.

Determining Quality of Life: How Do You Know if What You Are Doing Is “Working”?

In the early stages of dementia, determining quality of life can be as easy as asking the person, “How good do you feel?” (Jonker, Gerritsen, Bosboom, & Van Der Steen, 2004). However, in later stages of dementia, people may not be able to answer this question verbally. In this case, the caregiver, family, and friends can look for clues by paying attention to emotional responses – laughing, smiling, frowning, looking worried, restlessness, or even just leaning in and making eye contact, which is a sign of interest in something (Lee, Algase, & McConnell, 2013). In early stages of dementia, ask them how they are feeling. Ask them if they would like to do something – they can initiate much of their own activities and preferences. In later stages, people with dementia depend more on their environment and their caregivers to provide them with something of interest, because they have lost the ability to initiate activities themselves (Smit et al., 2016).

Summary

Caregivers often feel comfortable in understanding that they need to meet the physical care needs of the person with dementia. Research has shown us that they can also play an essential role in making an environment comfortable, pleasing, loving, engaging, and fun. Although the circumstances of dementia are difficult and challenging for both the caregivers and the people experiencing the disease process, those around them can look for the behavioral cues to guide them in providing the activities, interactions, and environments that yield interest and positive reactions, and avoiding the triggers of agitation, anger, or other negative reactions. While we cannot ensure that people with dementia won’t still feel confusion or negative emotions on occasions that are out of our control, , we can still recognize that they are sad or distressed and offer comfort and sensitivity to their experiences. Through simple adjustments to the environment and by providing opportunities for meaningful activities or pleasant experiences, caregivers can play a key role in maximizing the quality of life that people with dementia can maintain, despite their impairments.

References

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2017). Alzheimer’s and dementia caregiving center. Retrieved from http://www.alz.org/care/overview.asp

- Brod, M., Stewart, A. L., Sands, L., & Walton, P. (1999). Conceptualization and measurement of quality of life in dementia: The dementia quality of life instrument (DQoL). The Gerontologist, 39(1), 25-36.

- Jonker, C., Gerritsen, D. L., Bosboom, P. R., & Van Der Steen, J. T. (2004). A model for quality of life measures in patients with dementia: Lawton's next step. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 18(2), 159-164.

- Keyes, C. L. (2007). Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: A complementary strategy for improving national mental health. American Psychologist, 62(2), 95.

- Kitwood, T. (1997). Dementia reconsidered: The person comes first. Buckingham, UK:Open University Press.

- Lee, K. H., Algase, D. L., & McConnell, E. S. (2013). Daytime observed emotional expressions of people with dementia. Nursing Research, 62(4), 218-225.

- Schreiner, A. S., Yamamoto, E., & Shiotani, H. (2005). Positive affect among nursing home residents with Alzheimer's dementia: The effect of recreational activity. Aging & Mental Health, 9(2), 129-134.

- Smit, D., de Lange, J., Willemse, B., Twisk, J., & Pot, A. M. (2016). Activity involvement and quality of life of people at different stages of dementia in long term care facilities. Aging & Mental Health, 20(1), 100-109. Doi:10.1080/13607863.2015.1049116

- Tappen, R. M., & Williams, C. L. (2008). Development and testing of the Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias mood scale. Nursing Research, 57(6), 426-435. doi:10.1097/NNR.0b013e31818c3dcc

- Willemse, B. M., Downs, M., Arnold, L., Smit, D., de Lange, J., & Pot, A. M. (2015). Staffresident interactions in long-term care for people with dementia: The role of meeting psychological needs in achieving residents’ well-being. Aging & Mental Health, 19(5), 444- 452. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.944088

- Wood, W., Harris, S., Snider, M., & Patchel, S. A. (2005). Activity situations on an Alzheimer's disease special care unit and resident environmental interaction, time use, and affect. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias, 20(2), 105-118.

Authors

Elizabeth B. Fauth, Maria C. Norton, and Jessica J. Weyerman

Related Research

Utah 4-H & Youth

Utah 4-H & Youth