Gardening in Clay Soils

Introduction

Soils with high clay content create planting and maintenance challenges for gardeners. Soil textures with high clay content include clay, silty clay, sandy clay, clay loam, silty clay loam and sandy clay loam. Those textures with the word “loam” in their name generally have between 20 to 40% clay, with varying amounts of sand and silt indicated by the names. The other textural classifications generally indicate soils with more than 40% clay. The sandy clays have a predominance of sand (greater than 45%) and the silty clays have a predominance of silt (greater than 40%), in addition to their high clay content. Soil texture can be determined through a soil test (see www.usual.usu.edu for more information on soil testing in Utah). Generally, soils that contain greater than 30% clay are considered unacceptable as topsoil material because soils with high clay content slow water infiltration and air penetration. Clay soils can be difficult for roots to penetrate, and can be very hard for gardeners to cultivate. Gardeners with clay soils may choose to bring in an alternative soil and garden in raised bed boxes, or amend existing clay soil with loamy topsoil or well-composted organic matter.

Raised bed boxes can be an alterntaive for gardens with heavy clay soils

What is Clay and Where is it Found?

Clay is the smallest of the three soil particle sizes, sand, silt and clay. Clay particles are less than 0.002 millimeters in diameter, feels sticky when wet, and can be formed into a ball. Individual clay particles are not visible to the naked eye and often accumulate in the lower soil layers (the subsoil) as particles travel with soil water or mechanical sorting down through the topsoil. Topsoil is generally higher in sand, silt, organic matter, and microorganisms. Subsoil is often higher in clay and salts. Clay particles are plate-shaped and can align in sheets which can compact and form hard soil layers called pans. Landscapes around new construction often have surface soils that are high in clay. This happens when topsoil is removed to build a foundation and the newly exposed subsoil (high in clay) becomes the surface material. The original topsoil should be replaced when construction is over. It also is important at that time to break up any compacted subsoil so plant roots can penetrate the soil.

Clay soils may form cracks or crusts as seen in this soil located at a construction site.

How Can Clay Soils Be Amended?

The best amendment for clay soils is organic matter. Organic matter refers to materials derived from onceliving sources. Composted tree bark, wood chips, straw, leaves, aged animal manures, and green-waste are all examples of organic matter. Organic matter can be purchased in bags or bulk at nurseries and garden centers. Read the label or ask the company selling the product for a list of ingredients that make up the compost blend. Examples of common materials in blends include, green waste, bark or wood chips, peat moss, manure, topsoil, vermiculite and perlite. Gardeners can also make their own compost at home. Sand is not a good amendment option for clay soils because the wrong proportions of sand and clay can result in a material that is too compact and cannot be worked, similar to low-grade concrete. When topsoil or organic matter is added to clay soil, it should be thoroughly mixed in.

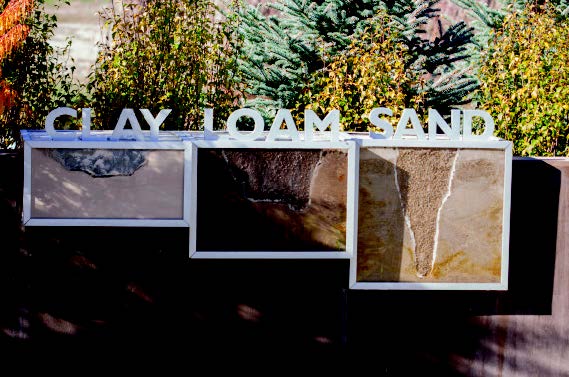

This educational display at Jordan Valley Conservation Garden Park in Salt Lake County shows

water movement throughclay, loam, and sandy soils.

What are Garden Management Implications of Clay Soils?

Clay soils should be managed differently from sandy soils. Irrigation water penetrates clay slowly (0.01 to 0.5 inches of water per hour), so water should be applied to the soil surface at a slow rate over a long period or it will run off. It takes approximately 1 inch of water to recharge a 1 foot depth of clay soil. Once clay soil is saturated with water, it takes a long time to dry-out. Air cannot move into saturated soil very well, but aeration is vitally important for root growth, microbes and good soil chemistry, so clay soils need to dry out somewhat before applying more irrigation water. That way water is available for root uptake in the smaller soil pore spaces, but is drained from the larger pore spaces, making air available to plant roots. Soil textures with high clay content at the soil surface tend to form a crust, particularly if the soil is compacted or has been impacted by water droplets from sprinkler heads or precipitation. Crusting can influence seedling emergence and root growth and distribution, and can reduce plant productivity. When checking soil moisture level, do not use sight alone. A surface crust may appear dry even though the soil immediately underneath is saturated.

Clay soil retains most nutrients very well because of its negative charge and high surface area, so clays usually are very fertile. In general, gardeners do not need to add fertilizer as frequently to clay soils as to coarser soil textures. If soil test results reveal high phosphorus (P) or potassium (K) levels, it is not necessary to add these nutrients to plants growing in clay soils. It is typically recommended to add nitrogen (N) on an annual basis. Clay should not be tilled when wet due to its tendency to compact. Tilling soils with high clay content when wet can result in the formation of large soil clods. Foot and vehicle traffic should also be avoided when clay is wet.

Plants that Grow Well in Clay Soils

Plants with tolerance of waterlogging, compaction, or poor aeration should be favored in clay soils. Plants that require well-drained soil will grow best in better draining, coarser textured soils like sands and loams. Here are a few examples of trees found in Utah that will grow well in clay soils.

| Common Name | Scientific Name |

|---|---|

| Alder, European or Common | Alnus glutinosa |

| Alder, Thinleaf or Mountain* | Alnus tenuifolia |

| Arborvitae, Oriental | Thuja (Platycladus) orientalis |

| Baldycypress | Taxodium distichum |

| Balm-of-Gilead Poplar | Populus candicans |

| Birch, River | Betula nigra |

| Birch, Water* | Betula occidentalis |

| Boxelder or Ash-leaved or Manitoba Maple* | Acer negundo |

| Cottonwood, Black* | Populus trichocarpa |

| Cottonwood, Eastern | Populus deltoides |

| Cottonwood, Fremont* | Populus fremontii |

| Cottonwood, Narrowleaf* | Populus angustifolia |

| Dogwood, Red-osier or Red-stemmed^ | Cornus sericea |

| Elder, Blue* | Sambucus cerulea |

| Elm, Camperdown | Ulmus glabra ‘Camperdownii’ |

| Elm, Siberian or Chinese | Ulmus pumila |

| Fringetree or White Fringetree | Chionanthus virginicus |

| Honeylocust | Gleditsia triacanthos |

| Maple, Freeman | Acer x freemanii |

| Maple, Red | Acer rubrum |

| Maple, Silver | Acer saccharinum |

| Mulberry, Red | Morus rubra |

| Mulberry, White | Morus alba |

| Oak, Sawtooth | Quercus acutissima |

| Oak, Swamp White | Quercus bicolor |

| Planetree, London | Platanus x acerifolia |

| Redcedar, Western | Thuja plicata |

| Rubber Tree, Hardy | Eucommia ulmoides |

| Sweetgum or American Sweetgum | Liquidambar styraciflua |

| White-Cedar, Northern or E. Arborvitae | Thuja occidentalis |

| Willows | Salix spp. |

*Utah Native

^ Shrub

This river birch is tolderant of soils with poor drainage.

This red-osier dogwood is tolderant of soils with poor drainage.

Utah State University Extension

Peer-reviewed fact sheet

Download PDF

Authors

Katie Wagner, Michael Kuhns, and Grant Cardon

Related Research