By Joseph Shahidi, University of Utah MCMP Graduate | August 17, 2022

IMAGE: A fire roars above a lakeside community.

When it Comes to Wildfire Resiliency, Preparation is Key

By: Joseph Shahidi, MCMP Graduate, University of Utah

Growing up in the west, wildfires were a normal part of every summer. I remember seeing devastating images on the news showing burning forests, fire crews creating breaks with pulaskis and mcleods, air tankers dropping retardant on soon to be engulfed trees, and sometimes the charred remains of some unrecognizable structure. Like many children I was naively fascinated, intrigued, and excited by these images (though, admittedly, the smoke that came into the area as a result of fire hundreds of miles away was not fascinating, intriguing, or exciting in the least).

I now appreciate that I’m one of the lucky ones. Having spent 28 years in western communities, I’ve never lost a house, livestock, or my favorite recreation area. I’ve never been evacuated or spent time in a community shelter. I’ve never had to work with my insurance company or FEMA to rebuild my life. While it may just be luck, I’d like to think that my avoidance of such situations is at least in part due to the preparation and forethought of those within my community for such an event.

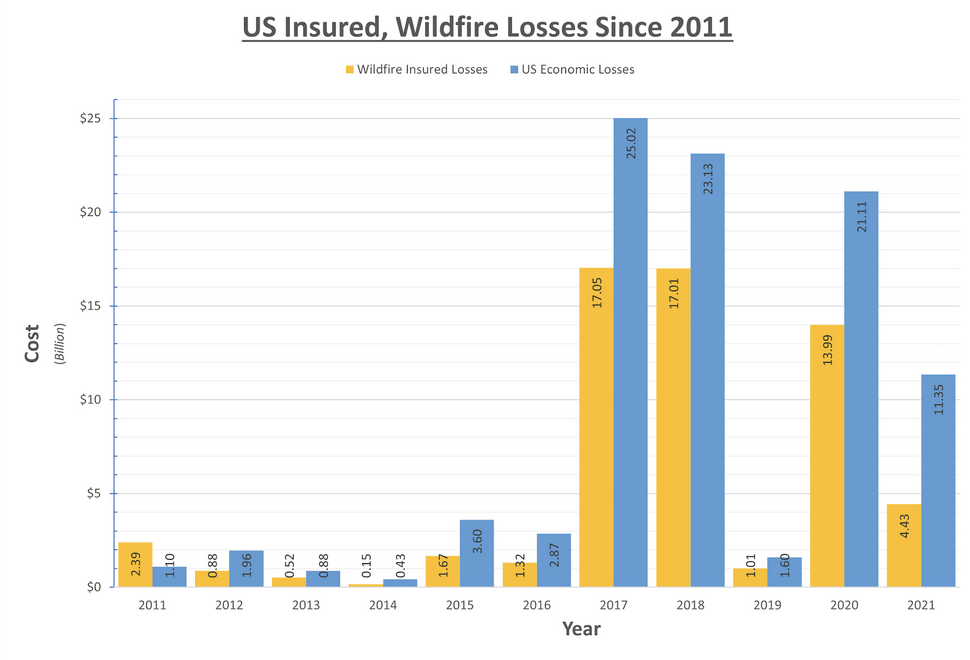

With global warming causing the summer fire season to become longer and more severe, we are seeing the undeniable increase in wildfire damage from decade to decade. Further complicating the situation, increased development within gateway and natural amenity region (GNAR) communities and their wildland urban interfaces (WUI), make the risk to persons and property seems unavoidable. According to AON PLC, recent insured losses within the United States have been significant: 2017, 2018, 2020, and 2021 are amongst the highest wildfire-related insured loss years in the last decade, with a cumulative total of around $52.5 billion. Throughout the country, communities big and small have struggled to adapt current infrastructure and prepare their new construction for the risk that development within the WUI present. While there are many methods of approaching this, one thing is for certain: an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

IMAGE: Graph of Wildfire losses since 2011. Source: AON PLC’s Insured and Economic Loss Data

The good news is there are many things that communities can do to prepare for the possibility of a wildfire and reduce their risk. Organizations such as the American Planning Association, National Fire Protection Association, the National Interagency Fire Center, and the EPA have all produced plans and resources to help communities reduce their risks and improve community resiliency. These resources offer a variety of expert knowledge and best practices to help communities take action to prepare for wildfire and reduce their risk.

Here are some basic things communities need to think about in planning for wildfire:

1. View and plan for natural disaster at a regional scale:

Natural disasters vary in size, but are rarely confined to a single municipality or county. Understanding and developing strategies on a regional level allows for increased resiliency and improves coordinated intergovernmental response. The adaptation of current policies and regulations to address deficiencies and enhance strengths of adjacent jurisdictions allows for more appropriate mitigation and timely response.

2. Determine areas’ susceptibility:

Not every community has the same risks, conditions, or capacity. Understanding current land uses and risk areas is vital in improving mitigation efforts. While code updates ensure that the risks to new development is reduced, finding ways where older and more susceptible areas of the community can be supported in mitigation efforts is essential to resiliency. The USDA Forest Service’s Wildfire Risk site is a good place to start in determining high risk areas within your community, though on-the-ground analysis is necessary for a complete understanding.

3. Increase capacity on an individual level:

While government policy can provide incentives to improve the resiliency of developed areas within its jurisdiction, it is also important to increase individual capacity. This is exemplified by California’s Fire Safe Councils; community organizations that foster community awareness and build individual capacity and preparedness improving mitigation, response, and recovery efforts. With nearly 150 chapters throughout the state, these grassroots organizations allow neighbors to help each other prepare for such events.

4. Learn from past experience:

When an incident does occur in your area, use the recovery phase to determine the community’s accomplishments and priorities. Figure out what worked well in your preparation efforts and what can be improved. On that note, why stop there? Use other communities as a resource and use their experience to improve policy and infrastructure in your own community! Following the Angor Fire (2007), the Emergency California-Nevada Tahoe Basin Fire Commission was founded to create a set of recommendations to reduce Lake Tahoe’s risk of wildfire. Their report, which was updated a decade later, outlines some of their successes and areas where improvement can continue to be made. These efforts have been credited with reduced impacts from last year’s Caldor fire.

5. Understand that the developed and natural world effect each other:

Recent studies have pointed to human ignition on private lands as the major cause of cross-boundary wildfire in the west. It is important for communities to develop the built environments that anticipate this risk and mitigate factors which will adversely affect property, people, and the natural environment. Implementing appropriate policies, land uses, and design standards for WUI areas can mitigate unintended ignition hazards. This not only protects communities, but also ensures that the environment that we enjoy is protected from incidents.

While wildfires can be tragically destructive, they are also incredibly important to ecosystem health—and they are inevitable. This is particularly the case in gateway communities where the very open spaces that make these regions desirable are often reliant on and/or prone to burning. We cannot (and should not) totally prevent wildfire, but we can do things to prepare our communities, minimize impacts, and otherwise be fire-wise.

For more information on and specific tools to help with improving community fire preparedness, please check out the Wildfire Preparedness Toolkit on the GNAR initiative’s website.

Joseph Shahidi is a graduate of the University of Utah’s Master of City and Metropolitan Planning program. Amongst other things, his academic interests include growth policies which create sustainable and resilient communities, while still protecting natural areas .He wrote this blog while a student in the GNAR Workshop Class.