Crap Rolls Downhill: How a Crisis in Infrastructure Can Usher in Development

By: Ryanne Pilgeram, Ph.D.

I chose Dover, Idaho as a case study for my book, Pushed Out: Contested Development and Rural Gentrification in the US West, because its transition from bustling mill town, to economically depressed former mill town, to “upscale” waterfront community, seemed like the perfect example of changes we are seeing in the West. For my project, I interviewed community members who had lived In Dover for 90 years, newcomers, mayors, city clerks, and developers. I wanted to share what displacement feels like. I was surprised when I ended up spending much of my time talking about water and sewage.

There were the crass jokes, like the one a father who had been raising a newborn during the 6-year boil order heard: “flush your toilets, Dover needs water!” But there were also mountains of newspaper clippings and city council minutes detailing the challenges the community faced as they worked to access clean drinking water and a functional sewer system. Sitting amid my data, interviews, and the archival papers, I kept wanting to understand the relationship between their infrastructural crises and development. It seemed counterintuitive a community that once suffered under what was described as "something more at home in a third-world country than North Idaho"  (Buley, 1989) could become so valuable.

(Buley, 1989) could become so valuable.

As often happens, while feeling overwhelmed by piles of data I was introduced to David Harvey’s theory of the “spatial fix.” Reading his work, I realized that I was struggling to make sense of the decline in Dover because I hadn’t seen that I was in the middle of the story. I needed to put the context of what happened before and after the decline to make sense of who benefited from it. What I was seeing in Dover’s infrastructural crises was the middle step of Harvey’s theory—the destruction phase.

Harvey’s theory of the spatial fix suggests that to function, capitalism must:

1) Build a fixed space (or ‘landscape’) necessary for its own functioning at a certain point in its history” only to

2) “destroy that space (and devalue much of the capital invested therein) at a later point.” Then, after exhausting the resources within that built landscape, it

3) finally requires a spatial fix or the creation of “openings for fresh accumulation in new spaces and territories.”

Harvey argues that “capitalism could not survive without being geographically expansionary (and perpetually seeking out ‘spatial fixes’ for its problems)”.

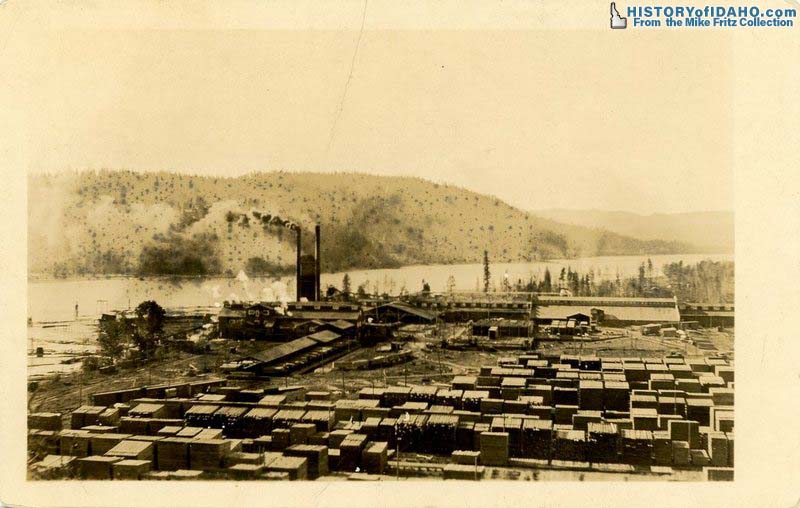

The first chapters of my book detail how Dover was created as a space for capitalism through the military force and financial support of the US government who waged war on the Indigenous people and gave away enormous tracks of the West the railroad and timber barons. This is the first step: building a space for capitalism. The twin convergence of railways and timber mills still leaves an indelible mark on the region. The Northern Pacific, for example, lobbied the US government for subsidies to construct the line and were given over 40 million acres. For every mile of track built, the federal government handed over 12,800 acres—double in the territories— to the company (Peterson 1929). Dover exists because a rail line was laid. Because enormous tracts of the West were wrenched away from Indigenous people and given to railroad companies who turned around and sold them to already rich men to build their fortunes. Fortunes built on the back of men who often worked in desperate and extraordinarily dangerous conditions.

Workers, of course, resisted these conditions primarily through collective action. From the timber wars of 1910s to the IWW’s organizing, North Idaho was a hotbed of labor activity. The mill (and mine) owners responded to worker demands in part through automation. For example, between 1979 and 2006 the number of mills in the North Idaho region shrank from 133 to 38, but the amount of lumber produced increases in nearly every reported period between 1979 and 2006—from 930,446 thousand board feet in 1979 to 1,746,050 thousand board feet in 2006 (Eric A. Simmons 2014:27). These seeming contradictions are explained by the closure of small mills and the growth of much larger ones that needed fewer people to do the same work through mechanization. One researcher found that “Nationwide during the 1980s production in lumber mills rose by almost 2% per year, while mill employment declined by 2% year” (Power 2006: 345).

When the mill in Dover closed in 1989 (six months after workers unionized) the community was left without these jobs, but it was also left without safe drinking water because that system had been built and maintained by the mill. When the mill site was subsequently bought and sold, the new owners simply abdicated responsibility for maintaining the water system.

This phase was the destruction phase of capitalism; where homes and land are devalued because they lack access to basic infrastructure. In Dover, residents were faced with a six-year boil order and left with houses they cannot sell. The mill owner is not held accountable—at all—for the failing water system.

This phase was the destruction phase of capitalism; where homes and land are devalued because they lack access to basic infrastructure. In Dover, residents were faced with a six-year boil order and left with houses they cannot sell. The mill owner is not held accountable—at all—for the failing water system.

Instead, the community moves mountains. First, they incorporate to become an actual “city” so they can apply for federal infrastructure grants for low-income communities. It is in the process of securing one of these grants and attempting to work with the mill owners to find a place to situate the new sewer system that the mill owners take the City of Dover to court and a judge forces them to rezone the mill site for a “Planned Use Development” (PUD). As the people of Dover attempted to save their community by accessing loans for low-income communities to rebuild their water and sewer systems, the city of Dover increased the value of the mill site. In other words, the mill owners saw huge financial gains because they failed to provide drinkable water.

My project argues that rural gentrification is the result of a rearrangement of the economic system in a way that seems natural but is designed to exploit the landscape and workers in new ways. The mill owners, having allowed the infrastructure Dover to deteriorate to the point it no longer functioned, reorganize its operations to sell the natural beauty of the area. The final step in the “spatial fix” was increasing profit by repackaging natural resources as scenic amenities for those who have accumulated wealth outside of the area. This framework then suggests that rural gentrification is not a new phenomenon, but rather an expected outcome of the routine functions of capitalism.

As I talked to people in Dover— particularly the newcomers —the desire for community and connection came up frequently. But the development was designed for consumption and profit, not for community connection. It is should not be surprising, then, that residents would find it difficult to find make those connections. If, for example, you look out the window of the old Dover Community Hall, the new homes are so close it seems like you might be able to peer inside. But the new homes are built with their backs to the old Dover Community Hall so that they can face the lake and river.

One of the key insights from my research for communities is understanding the link between infrastructural crises and gentrification. Today, the natural resources of the Pend Oreille watershed are seen as scenic amenities to those who have accumulated wealth outside of the area.

The grandchildren of folks who once earned a living clearing timber are now clearing tables at a restaurant on the development. In 2022 the tipped wage in Idaho is $3.25 an hour.

Works Cited:

Buley, Bill. 1989. "Dover's 'Boil Water' Order to End Next Fall" in Bonner County Daily Bee on December 21.

Harvey, David. 2001. "Globalization and the “Spatial Fix” Geographische Revue (2):223–30.

Harvey, David. 2014. Seventeen contradictions and the end of capitalism. Oxford University Press, USA.

Peterson, Harold F. 1929. "Some Colonization Projects of the Northern Pacific Railroad". Minnesota History 10(2):127-44

Power, Thomas Michael. 2006. "Public Timber Supply, Market Adjustments, and Local Economies: Economic Assumptions of the Northwest Forest Plan." Conservation Biology 20(2):341-50.

Simmons, Eric A, Steven W Hayes, Todd A Morgan, Charles E Keegan, and Chris Witt. 2014. Idaho's Forest Products Industry and Timber Harvest, 2011." Resource Bulletin. RMRS-RB- 19. Fort Collins, CO: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 46 p. 19.

Ryanne Pilgeram, Ph.D., is an associate professor in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at the University of Idaho. Her research focuses on issues of inequality in the rural West and works to imagine how we can create thriving rural communities.