Seeing the Forest for the Trees: The importance of working with humans to achieve coexistence with animals on working lands.

By: Dr. Hannah Jaicks

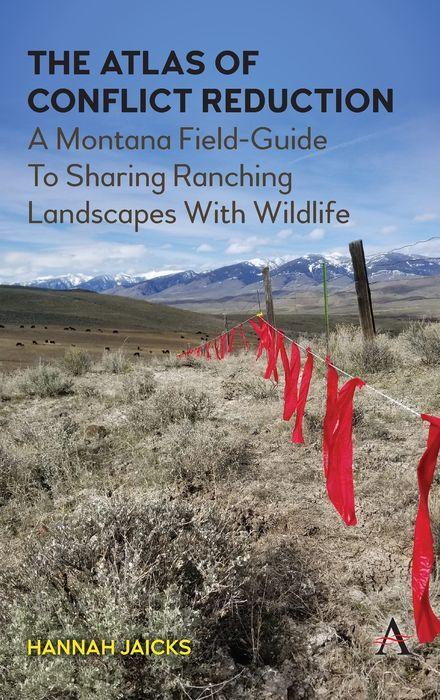

American ranchers and wildlife have long been entangled with another. The advent of shows like Yellowstone, and a surge in people chasing the magic (and the land) of Montana has put a spotlight on challenges facing GNAR communities from Gardiner to Glacier. While Kevin Costner may present a romanticized image of 21st century ranching, most landowners face much thinner margins and much larger anxieties, from the economic to the ecological. I wrote The Atlas of Conflict Reduction: A Montana Field-Guide to Sharing Ranching Landscapes with Wildlife to take readers into ranching communities to better understand these anxieties and how they're playing out on the ground in conflicts with wildlife.

With the host of planning, development, natural resource management, and public policy challenges facing ranchers, taking your frustrations out on an animal depredating your livelihood is an easy choice. Why then are we finding so many individuals "neighboring up" and working across the aisle to implement tools and strategies for sharing the landscape with wildlife? I wanted to find the answers and decipher strategies for how others can learn to support ranchers in their communities to do the same.

As a lifelong observer of human and animal behavior, about ten years ago I began investigating rancher/wildlife entanglements to determine what was missing from the conservation toolkit and see if an environmental psychology lens could shine new light on a centuries-old conflict. As with many of our polarized conflicts (conservation and otherwise), an awareness of how the human mind works and an understanding of what influences (and doesn’t influence) behavioral change was largely absent.  Livestock raising as a lightning rod of controversy is not a new phenomenon due to its central connection to wildlife conservation. Thanks to a dynamic history of interwoven proceedings like European settlement and displacement of native human and wildlife communities, early twentieth-century predator eradication policies and recent environmental regulations enabling wildlife populations to rebound, there is, unfortunately, a substantive basis to this adversarial relationship. Often absent from the accounts about the conflicts among ranchers and wildlife is a clarification about the power dynamics of decision-makers and influential lobbyists that contribute to and exacerbate these entanglements on-the-ground. The oversimplified dichotomy of ranchers versus wildlife has long persisted as a straw man in scientific, social, and political agendas, and it prevents attention to the underlying factors contributing to the conflicts as well as ensures no concrete solutions are identified. It also treats ranchers’ conflicts with wildlife as a cause of conservation crises rather than underscoring how they are actually an indicator of the broader set of issues facing the United States today.

Livestock raising as a lightning rod of controversy is not a new phenomenon due to its central connection to wildlife conservation. Thanks to a dynamic history of interwoven proceedings like European settlement and displacement of native human and wildlife communities, early twentieth-century predator eradication policies and recent environmental regulations enabling wildlife populations to rebound, there is, unfortunately, a substantive basis to this adversarial relationship. Often absent from the accounts about the conflicts among ranchers and wildlife is a clarification about the power dynamics of decision-makers and influential lobbyists that contribute to and exacerbate these entanglements on-the-ground. The oversimplified dichotomy of ranchers versus wildlife has long persisted as a straw man in scientific, social, and political agendas, and it prevents attention to the underlying factors contributing to the conflicts as well as ensures no concrete solutions are identified. It also treats ranchers’ conflicts with wildlife as a cause of conservation crises rather than underscoring how they are actually an indicator of the broader set of issues facing the United States today.

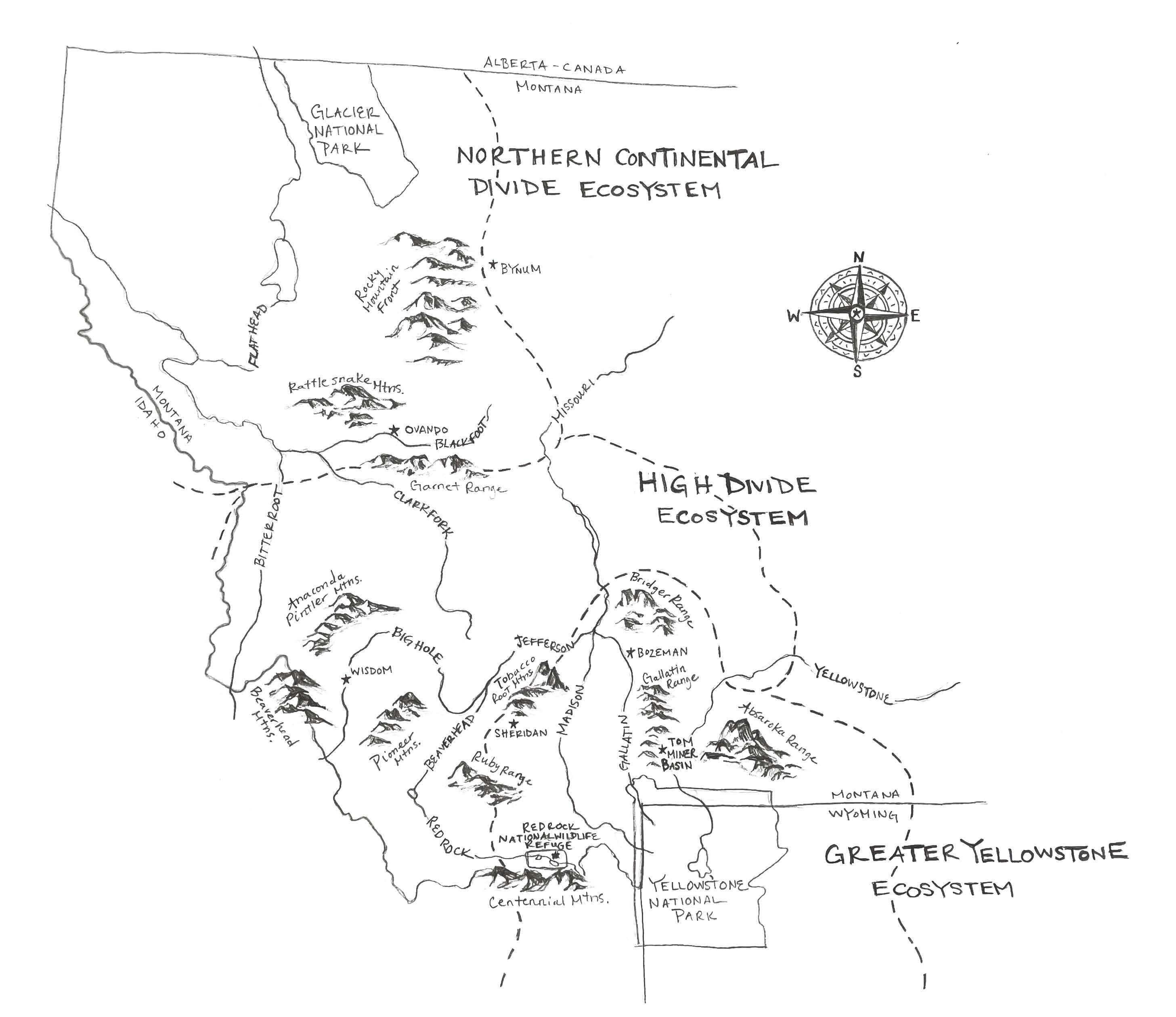

As a response, I journeyed into the heart of western Montana’s ranching communities to build a case for my central argument: ranchers’ conflicts with wildlife are symptoms of more systemic concerns like climate change, the dissolution of family ranches due to consolidation and globalization of agriculture, unaddressed impacts of persistent settler-colonialism, and the ever-expanding reaches of human development. After spending nearly a decade living, working, and playing amongst the human and animal communities, I published my book this past winter, The Atlas of Conflict Reduction: A Montana Field-Guide to Sharing Ranching Landscapes with Wildlife (Anthem Press, 2022), to make these underlying causes visible. Over the course of my book, I take readers with me on a journey through western Montana to a different valley in each chapter and showcase the place-based stories of everyday conservation heroes who practice regenerative ranching, provide consciously-raised agricultural products, advance strategies for collaborative conservation and protect vital habitat for endemic wildlife that would otherwise be developed and subdivided beyond repair. Each chapter introduces the reader to a different community and couples their stories with broader themes and ideas from the disciplines like modern psychoanalysis, human geography, and environmental history to better illustrate the issues ranchers face in attempting to maintain their livelihood among wildlife populations but also the opportunities ranchers take advantage of to overcome them and why. Using an ethnographic, grounded theory approach, I stitch together firsthand accounts with concepts like the Confirmation Bias, the cultural politics of conservation, and the pervasive mythology surrounding native and nonnative animals. Illustrations by Katie Shepherd Christiansen (Coyote Art & Ecology) of wildlife and conflict-reduction tools accompany the text, helping to underscore the vivid realities of shared landscapes and how they are achieved.

Over the course of my book, I take readers with me on a journey through western Montana to a different valley in each chapter and showcase the place-based stories of everyday conservation heroes who practice regenerative ranching, provide consciously-raised agricultural products, advance strategies for collaborative conservation and protect vital habitat for endemic wildlife that would otherwise be developed and subdivided beyond repair. Each chapter introduces the reader to a different community and couples their stories with broader themes and ideas from the disciplines like modern psychoanalysis, human geography, and environmental history to better illustrate the issues ranchers face in attempting to maintain their livelihood among wildlife populations but also the opportunities ranchers take advantage of to overcome them and why. Using an ethnographic, grounded theory approach, I stitch together firsthand accounts with concepts like the Confirmation Bias, the cultural politics of conservation, and the pervasive mythology surrounding native and nonnative animals. Illustrations by Katie Shepherd Christiansen (Coyote Art & Ecology) of wildlife and conflict-reduction tools accompany the text, helping to underscore the vivid realities of shared landscapes and how they are achieved.

Many aspects of life in the early twenty-first century go beyond easy analysis and resolution. The subject matter of this book is bound then to aggravate anyone who demands singular causes and fixed solutions. It is better for the rest of us to contend with and, perhaps, enjoy the richness of complexity. I am tough on everyone at various points in the book because I want us all to face what we have been so cleverly avoiding through our current scientific practices, social media engagement, and decision-making processes that simply reinforce what we already believe, think and feel. Henry Glassie, a legendary folklorist, sums up my ultimate goal, “We study others so their humanity will bring our own into awareness, so the future will be better off than the past.”

Regardless of readers’ stance on ranching and wildlife, this book will introduce you to ideas and accounts that you will likely find yourself agreeing and disagreeing with as you go. Whatever your assumptions or beliefs are at the start, my hope is that by the time you finish reading, you will approach the subject of coexistence–and any other contemporary environmental challenge–with a more nuanced, solution-oriented approach that integrates an understanding of how our minds work and what influences behavior. There is, sadly, no universal panacea to solve the types of modern conservation problems we face, but there are ways we can better address them. This book is a roadmap for how anyone concerned about the fate of our lands and their inhabitants can begin to do so.

Hannah Jaicks, PhD is an interdisciplinary scientist working with rural communities on how to coexist with native wildlife to improve the stability of wild and working landscapes for human and nonhuman animals and the author of The Atlas of Conflict Reduction: A Montana Field-Guide to Sharing Ranching Landscapes with Wildlife. She is currently the Working Lands Initiative Program Director for Future West based out of Sheridan, Montana. When she's not at work, she's winding up locally sourced, wildlife friendly wool for her latest knitting project to improve local textile supply chains.