018 - Native American Uses of Utah Forest Trees

Introduction

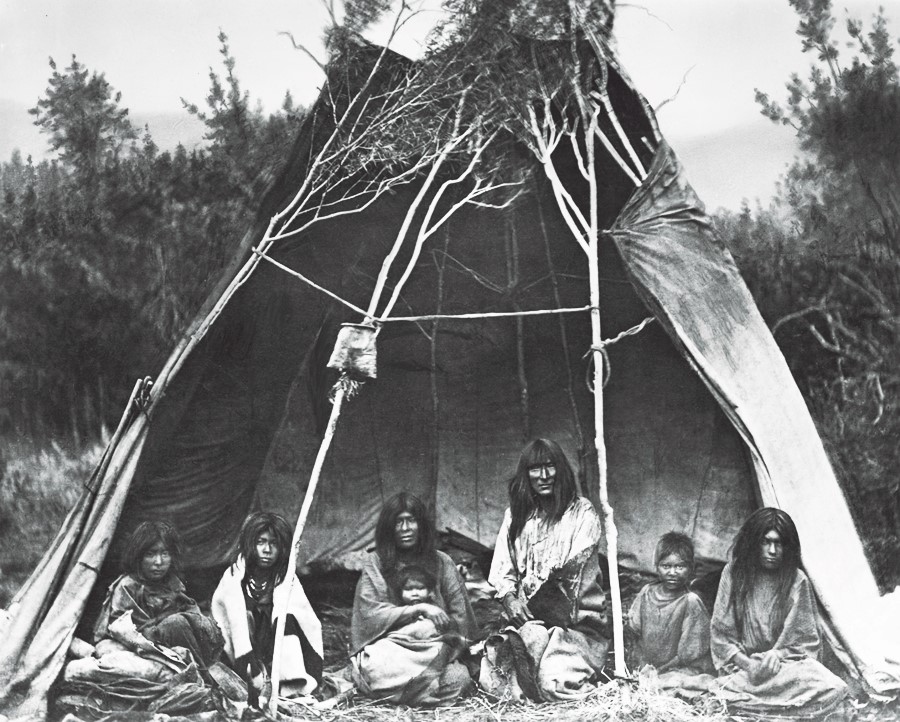

Bannock family uses young saplings to support their tepee at a camp in Idaho

Native Americans used a great variety of plants in their day-to-day existence, and although most of these practices are no longer current, many ethnobotanical studies have brought them to light. While anthropologists have focused primarily on native uses of herbaceous and shrubby plants, there are a number of sources that reveal native uses of trees as well. This fact sheet focuses on the uses of the most common trees of Utah forests, and covers most of the species mentioned in an earlier fact sheet titled “Utah Forest Types: An Introduction to Utah Forests.”

Of course, all tree species that grow in Utah also grow in the surrounding region, so native uses of trees by tribes outside of Utah have been included for a more complete discussion. However, no attempt is made to be comprehensive, and only tribes from the western United States and Canada are included. The principal source of the information presented here is a Native American ethnobotany database at the University of Michigan. The book Native American Ethnobotany by Daniel E. Moerman is based on this database and provides a source of additional information.

Native Americans used trees mainly for medicine, food, tools, shelter, and ceremonial aids. All but one of the trees discussed here is evergreen, and because evergreens share similar properties, there is some overlap in uses between species. For instance, the needles of evergreens were commonly used for tea, the pitch was chewed like gum, the inner bark was consumed for food or medicine, the wood was used for home and tool construction, and various parts were used for purification or cleansing, both physical and spiritual. Similarly, there is considerable overlap in the uses of these trees by different tribes. Therefore, in the accounts that follow, the individual tribes are mentioned only when the uses are unique to a particular tribe’s environment or belief system. The location of each tribe is noted when the tribe is first mentioned.

This information is presented only to foster cultural and historical understanding. If you are considering using any of these tree-based foods, medicines, or remedies, you should first do thorough research into their safety and potential dangers. A web search for “poisonous plants” would be a valuable starting point.

Pinyon - Pinus edulis and Pinus monophylla

Pinyon branches and cones with pine nuts

Pinyon is probably best known for its edible seeds, commonly called pine nuts (see “Pine Nuts: A Utah Forest Product” in Utah Forest News). Although there are two species of pinyon native to Utah, Colorado pinyon (Pinus edulis) and singleleaf pinyon (Pinus monophylla), they were used similarly by Native Americans, so they are dealt with together here.

Pinyon has a long list of medicinal uses. The pitch was used for a myriad of ailments including cuts, any kind of skin problem, digestive or bowel troubles, infectious diseases such as colds, influenza, and tuberculosis, venereal disease, sore muscles, rheumatism, fevers, and internal parasites. It was also heated and applied to the face to remove unwanted hair or prevent sunburn. The inner bark was eaten as an emergency ration or made into an expectorant tea. The needles were chewed and swallowed to increase perspiration to relieve fevers. Buds were chewed and made into a poultice for burns, or dried and pulverized to make a fumigant for earaches. Practical uses of pitch included making dyes or paints, gluing arrows, cementing turquoise jewelry, or waterproofing woven water jugs or baskets.

Pine nuts were a tremendously valuable food source, and there were many more ways to eat them than just raw or roasted. They could be ground into flour and rolled into balls, made into cakes or gruel, mixed with berries and stored for winter use, mixed with yucca fruit pulp and made into a pudding, kneaded into seed butter and spread on bread, or made into stiff dough, frozen, and eaten like ice cream. Some tribes ground them with the shells for additional flavor. The value of the nuts was increased by their periodicity—good cone crops could not be counted on every year. Generally a heavy crop of pine nuts was only expected once every seven years. This often was followed by a smallpox epidemic, perhaps due to many different groups coming together to share the harvest and possibly spreading the disease.

Virtually every other part of the pinyon also had a use. Pollen was used for ceremonial purposes, sometimes in place of cattail pollen. Pinyon wood was valuable for house construction since it was resistant to rot and wood-eating beetles, and it was also used to make useful items such as cradles, looms, saddle parts, tools, and toys. Charcoal from pinyon wood made the best black for sand paintings, and pinyons that had been struck by lightning were valued for ceremonial uses.

- Children of the Kawaiisu tribe of southern California wore cracked pine nut shells on their earlobes as ornaments.

- The Navajo of the southwestern United States had a taboo against shaking pinyon trees to bring down the nuts, and preferred to gather them after they had fallen naturally to the ground. They also smeared pinyon pitch on a person involved in a burial, and spread it on the forehead and under the eyes of those in mourning.

- The Hopi of northeastern Arizona applied the pitch to their foreheads when going outside the house as a protection against sorcery. They also put pitch onto hot coals and used the fumes to smoke people and clothes after a funeral.

- The Havasupai of Arizona put pinyon sprigs into cooking pits with porcupine, bobcat, or badger to improve the taste of the meat.

- The Shoshone used pine nuts to make pemmican. The pine nut was a staple in their diet. The cones were harvested in the fall by knocking them out of the tree with a long pole. The cones were then buried overnight to cause them to open.

Juniper - Juniperus osteosperma and Juniperus scopulorum

Ute horse corral made of juniper and pinyon wood

Utah Juniper

As with the pinyon, the two native tree-sized species of juniper in Utah, Utah juniper (Juniperus osteosperma) and Rocky Mountain juniper (Juniperus scopulorum), are not differentiated here as to native uses.

In contrast to pinyon, most medicinal uses of juniper came from infusions or boiled extracts of branches, twigs, needles, or cones rather than from pitch. Nevertheless, these preparations were used for a list of conditions just as long and varied: kidney trouble, heart trouble, hemorrhages, stomachaches, headaches, menstrual cramps, colds, fevers, smallpox, flu, pneumonia, venereal disease, diabetes, cholera, tuberculosis, chickenpox, worms, swellings, rheumatism, burns, sore throats, hives or sores, and boils or slivers. A strong decoction of the cones was even used to kill ticks on horses.

The bluish, berry-like cones containing one or two seeds were boiled and eaten, or dried and used to make a drink, or ground into meal and added to water for a drink or to make into cake. They were also pierced and strung for beads. The Okanagan-Colville tribe of British Columbia considered the cones to be poisonous and used them on bullets or arrowheads to kill people more quickly in warfare, yet they also made a drink from the cones and drank it in the sweathouse.

Juniper bark worked well as a torch or for tinder to start fires. It was also well suited for lining and covering pits for storing fruit, and for covering floors and thatching roofs. As with other trees, juniper wood had many uses, such as lodge construction, corrals, fence posts, horse yokes, spoked wheels used in a throwing game, drums, flutes, bows, and bowls (made from knots in the wood).

Juniper needles and boughs had additional protective powers over illness, death, and sorcery. Boughs were hung around the house during epidemics to drive germs away and were considered powerful medicine for driving away evil spirits associated with death. Hunters also rubbed themselves with juniper boughs for protection from grizzlies. Needles were burned ceremonially for their sacred, purifying smoke that could ward off illness, protect from witches, and remove fear of thunder.

- Cheyenne men of the Great Plains used juniper wood flutes to court women. They also used an infusion of juniper for sedating hyperactive people.

- The Navajo used the juniper for “War Dance medicine,” and also to rub on the hair for dandruff.

- The Shuswap of British Columbia used juniper to keep earwigs and bedbugs out of the house.

- The Blackfoot used juniper in the Sun Dance ceremony on the altar of the sacred woman.

- The Hopi held misbehaving youngsters in a blanket over a smoldering juniper fire to calm them down.

- The Shoshone used the bark to make clothing, moccasin insulation, and rope. The wood was used to make corrals for antelope drives.

Quaking Aspen - Populus tremuloides

Aspen bark was valuable as both food and medicine

Heavily relied on by numerous species of animals, aspen was also a great source of food, medicine, and wood for Native Americans. Many medicinal uses relied on the presence of salicin and populin, two precursors of aspirin that are present to some degree in all members of the genus Populus.

Aspen bark had the most medicinal uses; preparations were used to treat ailments such as stomach pain, colds and coughs, fevers, heart problems, and venereal disease, and to dress wounds, stimulate the appetite, and quiet crying babies. The inner bark was considered a sweet treat for children, and it could be eaten raw, baked into cakes, or boiled into syrup and used as a spring tonic. An infusion of the roots could be used to prevent premature birth. Even the white powder on the surface of the bark had uses: to treat venereal disease, to stop bleeding, and to apply to the underarms to prevent hair growth or as a deodorant and antiperspirant.

A poultice of shredded roots or a boiled extract of stems and branches was used for rheumatism, and the leaves were used to treat bee stings, mouth abscesses, and urinary problems. The buds could be boiled in fat to make a nasal salve for sore nostrils caused by colds. Healing salves were made by mixing the ashes of bark or wood with grease.

Practical uses for aspen wood were also many and varied. Aspen logs were used to make Sun Dance lodges, dugout canoes, and deadfall traps for bears. Poles provided tepee frames and scrapers for deer hides. Knots could be made into cups, and bark could be made into cording.

- The Thompson tribe of British Columbia used a preparation of the bark to rub on the bodies of adolescents for purification. Stems and branches helped with insanity caused by excessive drinking, and made a protective bath against witches.

- Anyone observing a liquid taboo in the Blackfoot tribe could suck on aspen bark.

- The Blackfoot also made whistles from the bark in the spring when it could be slid from the branches.

- The Apache of the American Southwest used the sap to flavor wild strawberries, and the Utes of Colorado and Utah considered it a delicacy.

- The Upper Tanana of Alaska mixed the ashes of burnt aspen wood with tobacco and used it as chewing tobacco.

- The Carrier of British Columbia used rotten wood for diapers and cradle lining.

- Aspen stems were used to make a hoop for the Navajo Evilway ceremony.

- The Shoshone used aspen for building shelters, as pole scrapers, and as a season marker.

Douglas-fir - Pseudotsuga menziesii

Douglas-fir cones were used to help stop the rain

Douglas-fir pitch was used for medicine, chewing gum, and glue

All parts of the Douglas-fir had medicinal uses. The pitch was used for cuts, boils, and other skin problems, coughs and sore throats, and injured or dislocated bones. It could be mixed with oil and taken as an emetic (to promote vomiting) and purgative (a strong laxative) for intestinal pains, diarrhea, and rheumatism, among other ailments. It was also taken as a diuretic for gonorrhea. The bark had antiseptic properties and was useful for bleeding bowels and stomach problems, excessive menstruation, and allergies caused by touching water hemlock. The needles were used for a good general tonic and a treatment for paralysis. Bud tips were chewed for mouth sores. A decoction or infusion of young shoots was used for colds, venereal disease, kidney problems, an athlete’s foot preventative, or an emetic for high fevers and anemia.

Douglas-fir didn’t provide quite as much food as some other trees, but as with many other evergreens, the pitch could be chewed like gum or eaten as a sugar-like food. The needles and young shoots could provide a tea, and seeds were reportedly used as food, though they weren’t nearly as large and nutritious as the seeds of the pinyon.

The wood found its way into such useful implements as snowshoe frames, bows, spear shafts, tepee poles, and dugout canoes. Boughs made good camping beds and sweathouse floors. Twigs could function as a coarse twine wrap in basket making, and pitch could be used as glue and a patching material for canoes. Rotten wood was used to smoke buckskin, thereby preserving and dying it. Many tribes had various ceremonial uses for parts of the Douglas-fir.

- The interior Salish tribes of B.C. ate a white, crystalline sugar that sometimes appeared on the branches during hot weather in early summer.

- The coastal Salish steamed tree knots and placed them in kelp stems overnight, then bent them to make fishhooks.

- The Okanagan-Colville of British Columbia used the branches as a purification scrub for the bereaved. The Thompson tribe used them in a similar fashion for good luck. They also chewed the peeled plant tops as a mouth freshener, and used the shoots in moccasin tips to help keep their feet from sweating. Hunters made a branch scrub to prevent deer from detecting their scent.

- The Karok used soot from the burned pitch to rub into the punctures of girls’ skin tattoos and the wood to make hooks for climbing sugar pine trees.

- The Northern Paiute of Oregon used the branches as a flavoring for barbecued bear meat.

- The Swinomish of Washington used the boiled bark on fish nets as a light brown dye to help camouflage the nets from fish.

- The Chehalis and Cowlitz of Washington used the cones as charms to stop the rain.

- The Shoshone used this tree for shelter and its sap for sealing water jugs.

Ponderosa Pine - Pinus ponderosa

Ponderosa pine in the Uinta Mountains of Utah with a scar made by Native Americans harvesting bark

Ponderosa pine pitch was used medicinally for sores and boils, aching backs and limbs, sore eyes, earaches, and as a general tonic. Heated needles were used to hasten the delivery of placenta, and a decoction was good for coughs and fever. Boughs were used in sweathouses for muscular pain. Plant tops were used to help with hemorrhaging and high fevers.

The sweet inner bark was used for food by many tribes (see the Summer 2004 Utah Forest News article “Ponderosa Bark Used for Food, Glue, and Healing”). A highly nutritious food source, it could be eaten raw, rolled into balls for a sweet treat, baked into cakes, mixed with corn and meat and used to flavor stew, or peeled off in strips and dried for later use. It was collected on cool cloudy days when the sap was running, and different sources have likened the taste either to sheep fat or lemon syrup. The seeds were also used for food, either raw or roasted, or dried and powdered and made into small cakes or bread.

Practical uses of ponderosa pine seemed to outnumber the food and medicinal uses. The pitch could be used as a kind of hair tonic, as glue for arrow making and other manufactures, and as a waterproofing agent for water jugs and moccasins. The bark was good for temporary shelters while out foraging, or for containers for sand painting pigments. The abundant long needles could be used to make baskets, insulate underground storage pits or the roofs of pit houses, or to provide a platform supported on a pole framework for roasting berries. The roots were used to make a blue dye, and the root fibers were used in basketry. The wood was valuable for large roof timbers, lodge poles, dugout canoes, ladders, fence posts, corrals, cradleboards, saddle parts, and snowshoes.

- The Utes used the pitch to glue rawhide to horses’ hooves to protect them from rocky terrain; they placed people against scarred trunks for healing.

- The Cheyenne used the pitch inside whistles and flutes to improve their sound.

- The Paiute used pitch to protect rock paintings.

- The Shuswap valued the bark as fuel because it cooled quickly and prevented enemies from knowing how long ago a camp was broken.

- The Flathead of Montana jabbed the needles into the scalp for dandruff.

- The Thompson used pitch on babies’ skin and claimed it made them sleep all the time.

- The Hopi attached needles to prayer sticks to bring cold weather.

- The Kawaiisu used a branch to hang the outgrown cradle of a male child in the hope he would grow strong like the tree.

- The Shoshone used the tree for shelter and the sap for sealing water jugs.

Limber Pine (Pinus flexilis) and Bristlecone Pine (Pinus aristata)

Limber pine and bristlecone pine were evidently not used as extensively as their lower elevation counterparts, but there are some records regarding these two species. The Shoshone used a poultice of heated pitch from bristlecone pine on sores and boils. The Navajo used limber pine as a cough and fever medicine, a good luck smoke for hunters, and a ceremonial emetic to induce vomiting. The Apache roasted limber pine seeds and sometimes ground and consumed them, shells and all.

Lodgepole Pine - Pinus contorta

Lodgepoles used for the home of a Ute chief in the eastern Wasatch Mountains, Utah

As with most evergreens, the pitch of lodgepole pine had a wide variety of medicinal uses. Internally it was considered good for colds, coughs, sore throats, tuberculosis, stomachaches and ulcers. External poultices were used for heart trouble and rheumatism, and a mixture of pitch, red axle grease, and Climax chewing tobacco was applied to boils. Heated pitch was mixed in a ratio of four parts pitch to one part bone marrow for use on burns. It could also be applied to a splinter in the skin, allowed to set, and then peeled off along with the splinter.

Medicinal uses were also found for other lodgepole pine parts. The needle tips were boiled to make an extract for paralysis, body sores, or constitutional weakness. An infusion of twigs with needles attached was good for the flu. An infusion of sprouts and bark was used for syphilis. Smoldering twigs were carefully applied to arthritic or injured joints for pain and swelling. The inner bark was eaten as a blood purifier and used as a cathartic (strong laxative) or general tonic. Like the pitch, it was considered helpful for tuberculosis, coughs, and stomach problems.

Once again, like most evergreens the pitch was chewed like gum, the needles were made into a tea, and the inner bark could be used for food as well as medicine. The latter was sweet and succulent in May and June when the sap was running, but it was hard to digest raw and was usually boiled. Although it was used to treat stomachaches, eating too much could cause that problem. The seeds could also be used for food, though like Douglas-fir seeds, they weren’t large enough to provide a lot of nutrition.

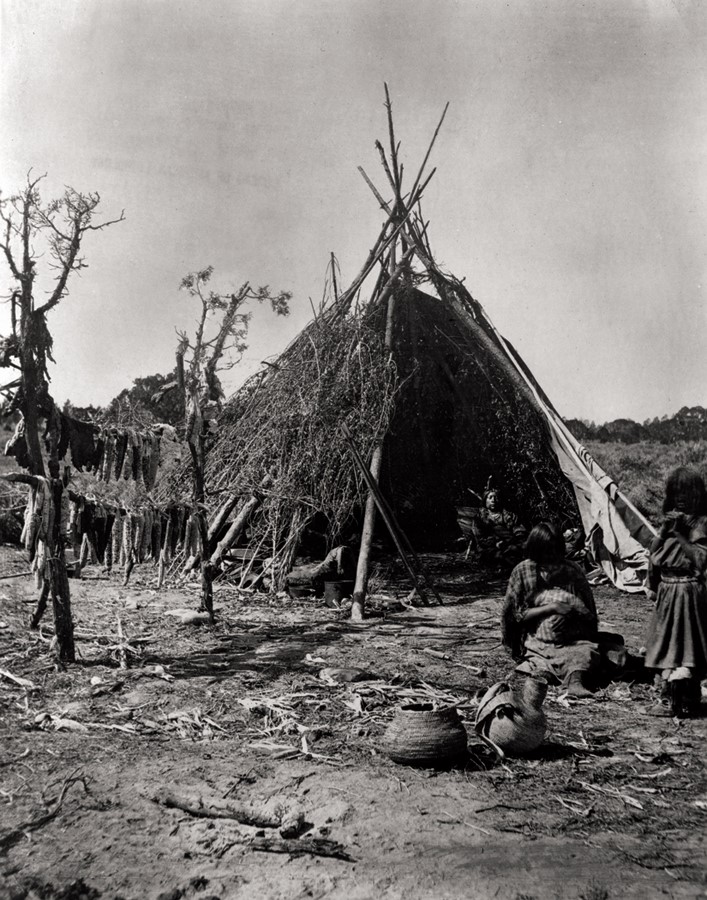

Practical uses for lodgepole wood included tepee and travois poles, and it was this use of the lodgepole that prompted Lewis and Clark to give the tree its name. The lodgepole was so valuable for tepee poles, in fact, (each tepee needed 25-30 poles) that Plains tribes would travel hundreds of miles to the mountains to get new poles every year. Other uses included bowls made from burls, fasteners on food storage bags, story sticks, fire tongs, board bending tools, and small totem poles.

- The Carrier painted pitch on the eye for snow blindness.

- The Klamath of Oregon reportedly used pitch on the inside of the eyelid to help sore eyes.

- The Thompson used a mixture of pitch, bear tallow, rose petals, and red ochre as a face cream with disinfectant properties that helped with blemishes, or as a kind of lotion for newborn babies. A salve of the resin mixed with animal fat was also applied to the body for purification after a sweatbath, or used for smoothing and polishing soapstone pipes.

- The Blackfoot used boiled pitch as a glue for headdresses and bows, and as a waterproofing agent for moccasins. They also used the wood to make wind chimes to present to newly married couples.

- The Kwakwaka’wakw of British Columbia used the pitch to trap hummingbirds. The birds’ hearts were then used in love medicines.

- The Okanagan-Colville used the bark to make temporary berry-picking containers.

- As with Douglas-fir, the branches of lodgepole pine were rubbed on hunters’ bodies in the Tolowa tribe of California and Oregon to hide the human scent.

- The Haisla of B.C. used burned twigs to make a pigment for tattoos, and to singe and trim hair.

- The Shoshone used this tree principally for building shelters, but also for building structures for ceremonies and for making travois.

Subalpine Fir - Abies lasiocarpa

Subalpine fir was known as the “medicine tree” by a number of tribes, and the list of ailments it was used for is truly impressive. A poultice of the needles was used to help with colds and fevers, and ground needles were used in horse medicine bundles, for skin diseases, bleeding gums, and as a baby powder for rashes from excessive urination. The smoke from a needle smudge was used to fumigate sick horses or human faces swollen from venereal disease, and was inhaled for headaches, fainting, and tubercular coughs. The pitch was used for general weakness, colds, tuberculosis, lung trouble, cuts and bruises, loss of appetite, and ulcers. It also provided a wound antiseptic, a means of inducing vomiting, and an external treatment for goiter. The bark was also medicinally valuable—an infusion could be given to horses for diarrhea, or it could be eaten as medicine for “shadow on the chest,” the beginning of tuberculosis. Branch tips were chewed for allergies caused by water hemlock.

Subalpine fir was not used nearly as extensively for food as other trees, although the inner bark and seeds could be eaten. The cones could be crushed into a fine powder and mixed with fat and marrow for a confection.

The needles could be used as a deodorant or mixed with grease to use as a hair tonic or perfume. They could also be placed on stoves as incense or pulverized and used as body and garment scents. The wood was used to make chairs and insect-proof storage boxes for dancing regalia. The branches were used on the floors of sweathouses and as bedding that could be easily changed every few days.

- The Blackfoot tied bags of needles on a belt and hung it around a horse’s neck for perfume. They also used a needle smudge for safety during severe thunderstorms, and sprayed chewed needles over ceremonial containers to purify them. Needles were also mixed with paint to make it smell better.

- The Cheyenne burned the needles as incense in ceremonies to help those afraid of thunder, to chase away illness, and to revive a dying person’s spirit. Their Sun Dancers used fir boughs for confidence, protection from thunder, and purification.

- The Okanagan-Colville rubbed dried, powdered bark on their necks and underarms as a deodorant.

Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmannii)

Engelmann spruce

Engelmann spruce was not as commonly used for medicine as the subalpine fir. However, the pitch was used for eczema and as a poultice for sores and slivers, an infusion of the bark was taken for respiratory ailments including tuberculosis, and a boiled extract of needles and pitch was taken for cancer or coughs. The bark was used for baskets, roof thatching, all kinds of utensils, and canoe coverings. The wood was used for shakes, clapboards, and framing timbers, and the limbs and roots could be shredded and pounded to make cord and rope. The Thompson believed that the spruce and redcedar would provide vivid dreams to anyone sleeping under them, as well as good luck for those who asked for it.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Patty G. Timbimboo-Madsen of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation for reviewing this fact sheet, and to the University of Michigan–Dearborn for providing and maintaining the Native American ethnobotany Web site that provided much of the content.

Published May 2011.