Ten Frequently Asked Questions About Growing Cannabis

Background

Cannabis sativa is the scientific name of the plant that includes both hemp and marijuana. It is one of the oldest cultivated plants in human history and has been grown for seed, fiber, oil, and medicine. There are generally three recognized subspecies (C. sativa subsp. sativa, C. sativa subsp. indica, and C. sativa subsp. ruderalis) and hundreds of varieties within Cannabis, each with unique characteristics.

1. What is the difference between cannabis, hemp, and marijuana?

Hemp and marijuana are closely related types of Cannabis that are often referred to as high and low THC cannabis. The difference between them is similar to the difference between sweet corn and field corn. Both are Zea mays, but sweet corn makes high-sugar kernels, and field corn makes starch-filled kernels. Sweet corn and field corn differ by only a few genes. Similarly, hemp and marijuana differ by only a few genes.

Cannabis varieties of both hemp and marijuana differ in outward appearance and in the production of over a hundred compounds in the class called cannabinoids. The two most common cannabinoids are delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the psychoactive compound responsible for the “high” often associated with Cannabis, and cannabidiol (CBD), a non-psychoactive sibling of THC with a unique set of characteristics and reported medical benefits (Nahler, 2019). These cannabinoids are the major difference between marijuana and hemp.

High THC Cannabis: Marijuana

Marijuana is the common name for Cannabis varieties that have been bred to have high THC levels, often containing 15–30% THC by weight. Marijuana is grown exclusively for the unpollinated female flower, where THC concentration is highest. Marijuana is classified as a Schedule 1 controlled substance by the federal government, but some states have legalized it for medical and recreational use. Where marijuana is legal, growers benefit from a remarkably high value for their crop. Recent marijuana prices range from about $750 to $1,750 per pound, depending on the quality and method of production (U.S. Cannabis Spot Index, 2018).

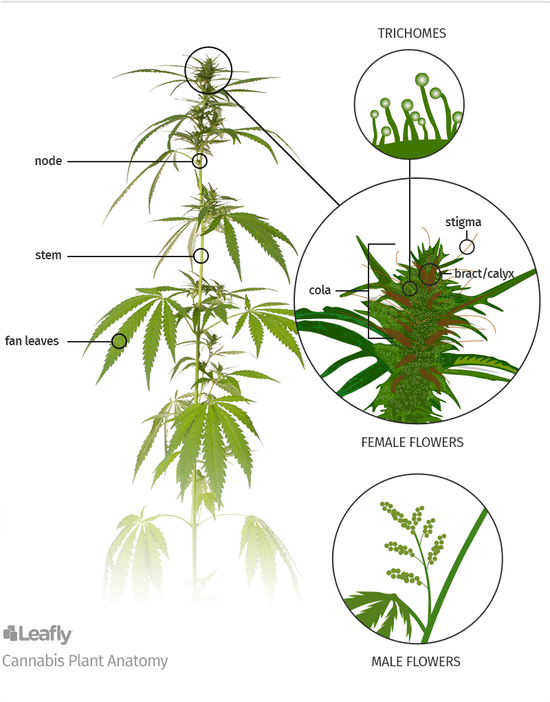

including both male and female reproductive

structures. Typically, these structures occur

on separate plants, but they can occasionally

occur on the same plant (hermaphroditic).

CBD is produced in trichomes, tiny

structures that occur in the highest density

on unpollinated female flowers. Image

used with permission from Leafly.

Low THC Cannabis: Hemp

Hemp is the common name for Cannabis varieties that have been genetically selected to have a THC content less than 0.3%. Since this THC level is low, hemp does not provide the psychoactive effect that marijuana does. Instead, hemp is grown primarily for CBD and other cannabinoids, and to a lesser extent, for its durable fiber and nutritious seed. The value of the crop varies depending on the intended use and the supply. Prior to the 2018 hemp market boom, gross returns were about $12,500, $1,300, and $750 per acre for CBD, fiber, and seed, respectively (Schluttenhofer & Yuan, 2017). Prices for CBD increased in 2018 to about $4.00 per percentage CBD per pound but then crashed to about $0.75 in 2019 to the present (personal communication with Utah hemp processors). Still, many in the industry predict that prices will stabilize in 2021. Due to this volatility, it is difficult to report current average prices. Prices vary greatly according to the intended end use, region, and specific contracts with buyers. Furthermore, state and national hemp prices are not tracked like other commodities, so it is difficult to find published reports of prices over time.

2. Why does plant gender matter?

Hemp differs from many other crops because it is primarily dioecious, meaning it has separate male and female plants. In addition, hermaphroditic plants with both male and female reproductive structures do occur. This creates unique issues for growers hoping to produce a high CBD crop because CBD is most concentrated on unpollinated female flowers (Figure 1). Pollination significantly reduces crop value, so an all-female field is important when hemp is grown for CBD. The pollination of hemp plants can reduce the essential oil yield from 2 to 0.9 gallons/acre, a 56% decrease (Meiner & Mediavilla, 1998). Male plants produce pollen that fertilize female plants, which causes seed production, lower flower counts, and decimates CBD levels (DeDecker, 2019). The distance that hemp pollen can travel is unknown, but due to cross-pollination risks, fields should be at least 3 miles apart (Small & Antle, 2003). However, some recommendations suggest up to a 15-mile isolation distance to be safe (DeDecker, 2019).

3. How and when can I detect plant gender?

Both male and female plants can be identified at the pre-flowering stage. Female flowers have two white fuzzy hair-like structures protruding from them, differentiating them from males early on. Male flowers are round, lack the white hairs, and generally occur in dense clusters (Figure 2). Cannabis is a short-day plant (requires longer periods of darkness than daylight to flower), so they will start to flower when day and night lengths are approximately equal. Male plants will produce pollen for a span of two to four weeks (DeDecker, 2019). If a male is identified in a hemp field grown for CBD, it should be removed and buried, burned, or carefully stored to prevent pollination of the females.

4. Should I purchase seed or clones?

There are two ways to produce a cohort of all females in hemp: clonal propagation and feminized seed. Clonal propagation involves taking a cutting from a mother plant and allowing it to establish roots. This method results in genetically identical, all-female plants with excellent vigor and predictable traits.

Feminized seeds are produced by treating female plants with chemicals such as silver thiosulfate, which can cause a female plant to develop male flowers that produce genetically female pollen (Lubell & Brand, 2018). The female pollen is used to pollinate a female flower, resulting in seeds that can be over 99% female. Feminized seeds are less expensive than clones but result in genetically different plants. They have a greater chance of producing male and hermaphroditic plants. Hemp grown from feminized seed requires careful and repeated scouting to remove male plants, increasing the total cost of production. This scouting should begin at the pre-flower stage when males can be distinguished (Figure 2) and continue throughout the entire flowering period. Plants grown from seed have the added benefit of potentially producing a stronger taproot if sown directly into the field, while plants grown from clones develop a more fibrous root system (Horner et al., 2019). This is generally true for many types of seed vs. clones and is not specific to feminized seed. However, germination rates in the field can be poor, and often seeds are germinated in trays and transplanted into the field. When this happens, the taproot may not get a chance to penetrate deep into the soil early on and negate the potential agronomic benefits of using seed.

In summary, both feminized seed and female clones have advantages and disadvantages that should be considered before growing hemp. It is critical that growers use extreme caution when purchasing feminized seed because there is currently no certification program for feminized seed in the United States.

5. Which varieties for cannabinoid production do best in Utah?

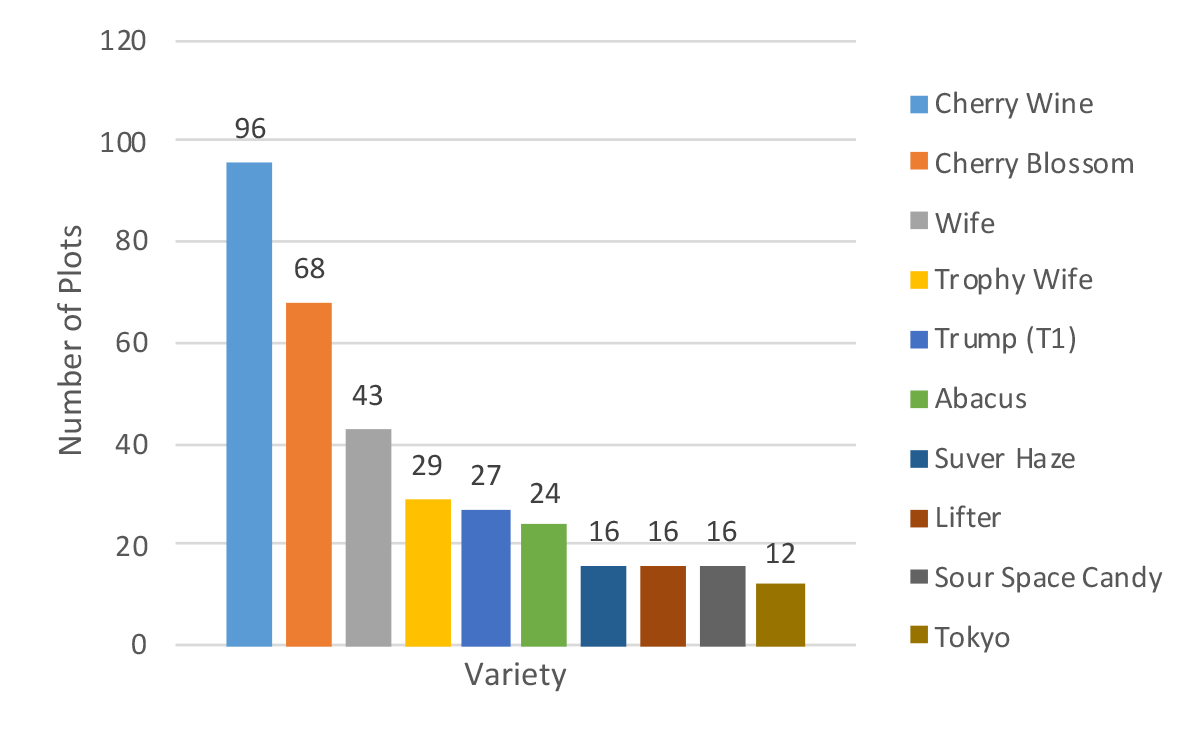

in Utah. Data provided by the Utah Department of

Agriculture and Food Industrial Hemp Program.

When selecting varieties to plant, consider the number of frost-free days, labeled cannabinoid production, and other factors of interest such as plant size, vigor, and growth habits. Several varieties grow well in Utah, but CBD and THC levels are highly variable among them (Figure 3). There is little testing of varieties, so evaluate information about a preferred option before selection, and consider planting several varieties. In general, focus on varieties that have a high CBD concentration and a low THC concentration. Avoid varieties that are prone to “going hot,” or exceeding the 0.3% THC limit. The field containing plants that are tested above this level by the state’s agriculture department must be destroyed.

In 2019, the Utah Department of Agriculture and Food (UDAF) tracked all varieties that were registered by licensed growers that year (Figure 3). ‘Cherry Wine’ and ‘Cherry Blossom’ were the most planted, and ‘Sour Space Candy’ and ‘Tokyo’ were among the least. Of the samples collected and tested, 10% exceeded the legal THC level of 0.3% and had to be destroyed. The varieties that most frequently went hot were ‘Abacus,’ ‘Lifter,’ and ‘Wife.’

6. What yield and CBD/THC ratio might I expect?

According to UDAF records, there were over 3 million industrial hemp plants grown in Utah in 2019 when hemp was first legalized. Growers harvested an estimated 800,000 pounds of biomass that year. The dry flower yield of the plants typically ranged from 0.75 to 1.5 pounds per plant. State tests determined an average CBD content of 5.3% and average THC content of 0.28%. This means the average CBD/THC ratio was about 20 to 1. Most varieties that have been studied in controlled environments have a similar ratio.

7. How much fertilizer and other inputs should I apply to my hemp?

Hemp can be grown in a wide range of environments and soils. In general, growers have found success growing hemp under field conditions favored by grain crops such as wheat and corn (Kaiser et al., 2015). Like many crops, hemp does best in soils with a pH ranging from about 6.0–7.0 (Harper et al., 2018). Most Utah soils have pH levels above this ideal range, but hemp produced in 2019 and 2020 tolerated higher pH levels. Well-drained soils are preferred, and due to its high sensitivity to compaction, avoid growing hemp in soils with high clay contents (Baxter & Scheifele, 2009).

The suggested fertilizer recommendations vary depending on region and initial soil fertility. Perform a soil test in the prior fall or early spring before planting to determine fertilizer needs. Fertilizer recommendations for corn or winter wheat (Cardon et al., 2008) provide a good baseline for fertilizer amounts that will help maximize hemp yield.

For pest management, there are currently few pesticides labeled for industrial hemp, so control weeds, insects, and diseases through careful planning and preventive practices. When hemp is grown in the same field year after year, pest pressure can increase, so crop rotation is the centerpiece of any pest management strategy. Only grow hemp in fields where weeds have been actively and successfully managed in previous years so the amount of weed seed in the soil seedbank is minimal. A stale seedbed technique for weed management is common, where the soil is prepared for planting and pre-irrigated, allowing weeds to germinate and be removed before planting hemp. After hemp plants are established and actively growing, limited pesticide options may necessitate hand-weeding or between-row cultivation. The hemp canopy closes quickly, helping reduce weed growth, but is dependent on row spacing and planting method.

8. How does frost affect CBD and THC levels?

Once mature, hemp is a relatively hardy plant and can withstand frost well. A study at the University of Vermont in 2018 tracked the difference in temperatures and resulting CBD levels of hemp plants between those with fabric row covers and those left uncovered. They found that though the uncovered hemp plants experienced below freezing temperatures several times throughout the study, the overall CBD concentration was unaffected. They also found that frost and cold weather can cause the plants to change color, but this has little to no impact on CBD or THC levels (Darby, 2019). Some have found that frost’s ability to change the color of hemp plants also varies depending on the cultivar or variety of the plant (Bolt, 2020). Like almost every other annual crop, hard frosts will stop plant growth and cause hemp plants to begin senescence.

Photo by Tina Sullivan.

9. How do I harvest hemp?

The harvesting methods for industrial hemp vary greatly depending on the intended uses for the plants. The major uses include oil, seed, and fiber.

CBD

Because no equipment exists on the market specifically to harvest CBD hemp, most of the harvesting process must be done by hand or by retrofitting existing equipment. The hemp is ready for harvest when the trichomes on the hemp buds shift from white to milky white. It is important to routinely monitor and test the plants to avoid exceeding the 0.3% THC limit while still maximizing the CBD content.

When harvesting hemp for oil, plants are commonly cut down at the base using a machete or blade of some kind (Figure 4).

dry. Photo by Cody Zesiger.

After they are cut, hang the plants upside down to air or heat dry (Figure 5). Breaking the plants down and separating them into individual branches will allow for better airflow and quicker drying. Ideal drying temperatures reported by some growers are between 60–70°F with humidity levels around 45–55%. Higher temperatures, as well as light and oxygen, can degrade cannabinoids and reduce flower quality. Therefore, maintain a cool and dark storage environment.

After the plants dry, growers strip the buds and leaves from the stems, either by hand or custom-built equipment (Figure 6). Bag the dried flowers and leaves and send them to a processor to have the oil extracted and dispose of the remaining plant.

Fiber

brush stripper. Photo by Tina Sullivan.

When growing hemp for the fiber, harvest plants between early bloom and seed-set or when about 20% of the male plants are flowering (William & Mundell, n.d.). Large parts of this process can occur using traditional hay-harvesting equipment, making it much simpler than other hemp harvesting methods.

The hemp is windrowed with a swather when mature, leaving about 4–6 inches of stubble in the field, where the hemp will then need to go through the retting process. Retting consists of leaving the cut hemp out in the field to dry for anywhere from two to five weeks. Retting helps break the bonds between the two types of hemp plant fibers: the bast (long outer fibers) and the hurds (short inner fibers). Rake the hemp two to three times throughout retting to keep the plants from rotting and remove leaves, making it easier to transport.

When the plants reach a moisture content of 15%, bale them using traditional baling equipment. The bales should have a moisture content of about 10%. Bale the hemp into either round or square bales, but round bales are less compact and therefore less susceptible to rotting.

Hemp Seed or Grain

Conventional grain harvesting equipment also accommodates harvesting hemp grain or seed. Use a combine to cut and chop the hemp plants. The hemp plants must be at 70–80% grain maturity at harvest to avoid seed shattering. The combine settings will be similar to those for grain sorghum, with the cutter bar raised about 40 inches off the ground. This decreases the amount of plant material going through the combine, thus reducing the risk for plants getting wrapped up in the machinery.

When harvest-ready, the hemp plants’ moisture will most likely be in the 15–30% range, making the seed or grain very susceptible to spoilage soon after harvest. It is best to clean the seed and dry it down to 7–10% shortly after harvest.

10. Who can process my hemp and where can I sell it?

This is a difficult question to answer as it varies greatly from place to place. Many growers have recently reported difficulty in finding places to sell and market hemp grown for oil. Hemp prices plummeted in 2020, and many frustrated growers could not process or sell their product. Some growers turned to specialty or direct marketing for income. Many lost large investments. Like any other specialty crop, it is wise to consult with an attorney to develop legal and binding contracts with hemp processors and buyers prior to investing in and growing hemp to guarantee that markets exist for harvested hemp. We recommended starting small to ensure that you do not lose more investment than you or your farm can afford. Unfortunately, we have received reports of farm failures due to large investments in unprofitable hemp acres. Thus, we suggest that growers use extreme caution when investing in production of hemp for CBD oil.

References

- Baxter, W. J., & Scheifele, G. (2009). Growing industrial hemp in Ontario. Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. http://www.omafra.gov.on.ca/english/crops/facts/00-067.htm

- Bolt, M. (2020). Frost and hemp, should growers worry? [Fact sheet]. Purdue University Extension. https://extension.entm.purdue.edu/newsletters/pestandcrop/article/frost-and-hemp-should-growers-worry/

- Cardon, G. E., Kotuby-Amacher, J., Hole, P., & Koenig, R. (2008). Understanding your soil test report [Fact sheet]. Utah State University Extension. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1825&context=extension_curall

- Darby, H. (2019). 2018 Cannabidiol cold tolerance trial [Fact sheet]. University of Vermont Extension. https://www.uvm.edu/sites/default/files/media/2018_Hemp_Cold_Tolerance_Trial.pdf

- DeDecker, J. (2019). Weighing the risk of cannabis cross-pollination [Fact sheet]. Michigan State University Extension. https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/weighing-the-risk-of-cannabis-cross-pollination

- Harper, J. K., Collins, A., Kime, L., Roth, G. W., & Manzo, H. E. (2018). Industrial hemp production [Fact sheet]. Penn State University Extension. https://extension.psu.edu/industrial-hemp-production

- Horner, J., Ohmes, A., Massey, R., Luce, G., Bissonnette, K., Milhollin, R., Lim, T., Roach, A., Morrison, C., & Schneider, R. (2019). Missouri industrial hemp production [Fact sheet]. University of Missouri Extension. https://extension.missouri.edu/publications/mx73

- Kaiser, C., Cassady, C., & Ernst, M. (2015). Industrial hemp production [Fact sheet]. University of Kentucky Extension. https://www.uky.edu/ccd/sites/www.uky.edu.ccd/files/hempproduction.pdf

- Lubell, J. D., & Brand, H. M. (2018). Foliar sprays of silver thiosulfate produce male flowers on female hemp plants. American Society for Horticultural Technology, HortTechnology, 28(6), 743–747. https://journals.ashs.org/horttech/view/journals/horttech/28/6/article-p743.xml

- Meiner, C.H. & Mediavilla, V. (1998). Factors influencing the yield and quality of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) essential oil. Journal of the International Hemp Association, 5(1) pp. 16–20.

- Nahler, G. (2019). Cannabidiol and contributions of major hemp phytocompounds to the “entourage effect;” possible mechanisms. Journal of Alternative, Complementary & Integrative Medicine, 5(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.24966/ACIM-7562/100066

- Schluttenhofer, C., & Yuan, L. (2017). Challenges towards revitalizing hemp: A multifaceted crop. Trends in Plant Science, 22(11), 917–929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2017.08.004

- Small, E. & Antle, T. (2003). A preliminary study of pollen dispersal in cannabis sativa in relation to wind direction. Journal of Industrial Hemp, 8(2). https://www.votehemp.com/PDF/Small2003JIH.pdf \

- U.S. Cannabis Spot Index. (2018). Cannabis benchmarks. Retrieved October 11, 2019, from https://reports.cannabisbenchmarks.com/

- Williams, D.W., & Mundell, R. (n.d.). An introduction to industrial hemp, hemp agronomy, and UK agronomic hemp research [Fact sheet]. University of Kentucky Extension. https://hemp.ca.uky.edu/sites/hemp.ca.uky.edu/files/uk_ih_information_for_agents3.pdf

Published June 2021

Utah State University Extension

Peer-reviewed fact sheet

Authors

Matt Yost, Megan Baker, Mitch Westmoreland, Tina Sullivan, Jody Gale, Cody Zesiger, Earl Creech, and Bruce Bugbee