Accepting Uncomfortable Emotions:

Learning From Car Dashboards and Manure

“Just think more positively.” “Pull yourself together.” “Get over it.” “Quit worrying.” Most of us have heard (and said) this advice many times. For agricultural producers, long hours coupled with challenging, unpredictable conditions can give rise to challenging thoughts and feelings at times. Conventional wisdom maintains that uncomfortable, distressing, or painful thoughts and feelings are “bad,” can be controlled by “thinking positively,” and are not healthy or normal. There is evidence that being optimistic, “finding the silver lining,” or seeing the benefits of hardship are beneficial for us. However, some people think this means that we should avoid the negative. The fact is that we all experience uncomfortable, distressing, and painful thoughts and feelings at times. There is no way to go through life without our minds reminding us of our mistakes, worries, or the painful gap between what we want and what we have (Hayes, 2019).

Understanding Thoughts: Getting Hooked, Avoiding, or Accepting

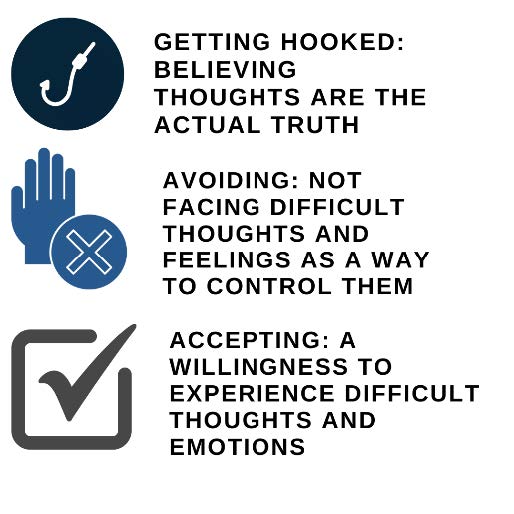

Thoughts like, “I am a failure as a rancher,” have likely been experienced by most ranchers at some point, particularly after conflict with others, exhaustion, or repeated worry. When distressing thoughts and feelings like this come, there are three general ways we can respond. First, we can treat these thoughts as if they represent something real or factual. Believing that this thought is the actual truth is what scholars call cognitive fusion, or “getting hooked,” and people who use this technique tend to have poorer mental health and lower quality of life (Bramwell & Richardson, 2018; Faustino et al., 2021). Why? When we “get hooked” by difficult thoughts, and believe they are true, we feel even worse, and we lose the ability to engage effectively with challenging situations, such as marriage, raising a family, and making a living.

Second, when we are faced with difficult thoughts, we can avoid them (psychologists call this experiential avoidance). Avoiding difficult thoughts and emotions is a way to control them, and for a short time, it can “work” (Harris, 2019). Thinking “I am a failure as a rancher” is distressing; experiential avoidance might mean “zoning out” while you binge-watch TV. Over the next few hours, you don’t have to experience that thought, which feels better. Unfortunately, avoiding our thoughts and feelings or trying to control them leads to patterns of avoiding the things we find the most meaningful (Pavlacic et al., 2021). This is because the people and things we care most about are the ones most likely to trigger these feelings and thoughts (Harris, 2019; Hayes, 2019). Avoiding difficult experiences is detrimental over the long term (Coutinho et al., 2019; Fernández-Rodríguez et al., 2018)

The third option runs counter to conventional wisdom yet has been shown to lead to multiple positive outcomes. Rather than “getting hooked” or avoiding/controlling, we can allow difficult thoughts and feelings to be there, traveling along with us as we pursue the things we care about. Scholars call this acceptance, which is a willingness to experience some difficult thoughts and feelings in pursuit of a meaningful life (Hayes, 2019). Note that acceptance is not accepting that the thoughts are true (that is “getting hooked”). Acceptance is simply accepting that you are experiencing what you are experiencing. In contrast to the other two responses, acceptance works in both the short term and long term and increases one’s ability to engage in meaningful activities (Fernández-Rodríguez et al., 2018). Acceptance has been shown to lead to multiple positive outcomes, including less depression, greater quality of life, improved health behaviors, and greater progress towards goals (Shallcross et al., 2010; Stockton et al., 2019).

Emotions: Lessons From the Car Dashboard

Thoughts are a combination of words and pictures (Harris, 2019); in other words, thoughts are a form of language that frames the meaning that we give to our experiences. Emotions are a combination of thoughts and physiological responses, such as accelerated heart rate, sweaty palms, or shallow breathing (Harris, 2019). Emotions are intended to move us to action, to respond to the world around us in a way that increases our chances of surviving.

Emotions are like indicators on a car dashboard. Sometimes they indicate something major that needs attention (the “check engine” light means you should take some action quickly). Other times they tell you the general state of the car: don’t wait too long to refill the gas but you are OK for now; the engine temperature is as it should be; tire pressure is lower than recommended. Note that the car dashboard tells you what is going on (indicators of the car’s function), but the dashboard doesn’t control the car. Emotions are similar: feelings of worry, depression, or hopelessness are indicators of our current state. Emotions can indicate what is going well, what needs attention soon, and what requires immediate action. Much like a check engine light means “act quickly,” frustration and a building temper might mean “take a break now; take a breath now.” And, while we may enjoy feeling “positive” emotions, such as happiness or satisfaction, more than “negative” emotions, such as fear or frustration, the fact is that all emotions are simply indicators of our experience, meant to inform—not control—our actions.

All emotions are simply indicators of

our experience, meant to inform—

not control—our actions.

Acceptance becomes a much more viable way of responding when we see thoughts and feelings in the proper light. You may not like what your emotions indicate, and you may disagree with your thoughts, yet as you practice acceptance, you choose to allow them to be with you as you engage in a meaningful life.

Misconceptions About Acceptance

Even though acceptance leads to multiple positive outcomes, sometimes people have misconceptions about acceptance. Two of the biggest misconceptions are the belief that acceptance means being passive and the belief that acceptance means believing all the negative things our minds say. Acceptance is about pausing long enough to understand what you are experiencing, with the intent to take effective action. When we are willing to accept our thoughts and feelings as thoughts and feelings, rather than treating them as reality, they can inform us of areas of our lives that need attention.

Lessons From Manure

For agricultural producers, manure is a part of life. Most everyone agrees that manure is unpleasant, dirty, and, well, crappy. Imagine if someone were to respond to manure the same way we are taught to respond to difficult thoughts and feelings—what if someone “hooked” with it and thought about it constantly? They would certainly end up seeing (and smelling) the world from a manure-colored perspective. Or what if a rancher tried to avoid manure, walking long distances just so they wouldn’t smell it? Neither of these responses works. Instead, we intuitively accept the manure—we notice it is there, acknowledge that it serves a purpose, make space for it, and then expand our focus to important parts of production.

These same four steps are used to help people become aware of and accept their own internal experiences—their thoughts and emotions (Harris, 2009). While it takes work, the skill of being open to our experience can be taught (Gloster et al., 2020) in therapy and through self-help resources and online courses (Fauth et al., 2021; Levin et al., 2014). Following are ways you can start practicing the four steps (adapted from Harris, 2009):

- Notice your thoughts and feelings. A good first step in cultivating acceptance is to notice what you are experiencing in the first place. Take a deep breath in and focus on your body. Is there tightness, pressure, pain, or discomfort in your body, such as your back, chest, or throat? Try to look at that feeling with curiosity, as if you had never encountered it before. What does stress feel like? What has your brain been telling you?

- Acknowledge that feelings serve a purpose. Much like the “check engine” light on a car, feelings are indicators that, when properly understood, can alert us to actions we should take to maintain our well-being. They do not control behavior, but they can inform behavior. For example, the feeling of “being overwhelmed” could inform you that you need more sleep or that you might benefit from asking for help with a task.

- Make space for the feeling. A scared horse in a small trailer might kick, damaging itself and the trailer; that same horse in an open pasture is much less likely to injure itself (Harris, 2009). Similarly, when we allow our feelings to be a part of our life, rather than trying to control them or stamp them out, they lose their influence in our life. To practice this, you might take a deep breath in and imagine that, in some sort of way, your capacity to hold the emotion is expanding just the way your stomach is. Allow the emotion to be there, but in a pasture, not in a small trailer.

- Expand your awareness. After noticing the feeling, recognizing that it serves a purpose, and making space for it, you can expand your awareness to take in other things. This is not an attempt to distract yourself; instead, it is like seeing the storm cloud on the horizon and the beautiful, clear blue sky above you. Once you acknowledge what you are feeling, you put yourself in a better position to act effectively—whether that means taking a break, talking with someone, or getting some urgent tasks finished.

Additional Activity

Touch is a powerful form of communication; it alters the body’s response to stress and lets people know you are there with them, care about them, and support them (Dreisoerner et al., 2021). If you want to go deeper with acceptance, try this: after noticing where in your body you feel the feeling most strongly, such as your stomach, chest, or forehead, bring your hand to that part of you and try to hold yourself as gently as you can. To get the right idea, think of a time when you have held someone else tenderly—a partner, a sobbing child, or an infant. Let your hand rest there, soothing and calm. Notice what happens to the feelings and your ability to engage with life (Harris, 2019).

Conclusion

Cultivating acceptance is a lifelong process because life is full of circumstances and situations that give rise to difficult thoughts and feelings. Each day and moment, we can choose whether to get hooked, avoid and control, or notice the thoughts and emotions as indicators, accept that they are there, and keep pursuing the life we want. If you make missteps and notice that you have become hooked (constantly focusing on the manure) or that you have been avoiding your feelings (constantly evading the manure), do not be ashamed; this simply means you are human. In fact, your noticing opens the door to a new choice—to accept the very thoughts and feelings you have been struggling with and learn from them (live with the manure), addressing areas of life that might need attention.

References

- Bramwell, K., & Richardson, T. (2018). Improvements in depression and mental health after Acceptance and Commitment Therapy are related to changes in defusion and values-based action. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 48(1), 9–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-017-9367-6

- Coutinho, M., Trindade, I. A., & Ferreira, C. (2021). Experiential avoidance, committed action and quality of life: Differences between college students with and without chronic illness. Journal of Health Psychology, 26(7), 1035–1045. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105319860167

- Dreisoerner, A., Junker, N. M., Schlotz, W., Heimrich, J., Bloemeke, S., Ditzen, B., & van Dick, R. (2021). Self-soothing touch and being hugged reduce cortisol responses to stress: A randomized controlled trial on stress, physical touch, and social identity. Comprehensive Psychoneuroendocrinology, 8, 100091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpnec.2021.100091

- Faustino, B., Vasco, A. B., Farinha-Fernandes, A., & Delgado, J. (2021). Psychological inflexibility as a transdiagnostic construct: Relationships between cognitive fusion, psychological well-being and symptomatology. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01943-w

- Fauth, E. B., Novak, J. R., & Levin, M. E. (2021). Outcomes from a pilot online Acceptance and Commitment Therapy program for dementia family caregivers. Aging & Mental Health, 0(0), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.1942432

- Fernández-Rodríguez, C., Paz-Caballero, D., González-Fernández, S., & Pérez-Álvarez, M. (2018). Activation vs. experiential avoidance as a transdiagnostic condition of emotional distress: An empirical study. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01618

- Gloster, A. T., Walder, N., Levin, M. E., Twohig, M. P., & Karekla, M. (2020). The empirical status of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 18, 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.09.009

- Harris, R. (2019). ACT made simple: an easy-to-read primer on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (2nd ed.). New Harbinger Publications.

- Harris, R., (2009). ACT with love: Stop struggling, reconcile differences, and strengthen your relationship with Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. New Harbinger.

- Hayes, S. (2019). A liberated mind: How to pivot toward what matters. Avery

- Levin, M. E., Pistorello, J., Seeley, J. R., & Hayes, S. C. (2014). Feasibility of a prototype web-based Acceptance and Commitment Therapy prevention program for college students. Journal of American College Health, 62(1), 20–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2013.843533

- Pavlacic, J. M., Schulenberg, S. E., & Buchanan, E. M. (2021). Experiential avoidance and meaning in life as predictors of valued living: A daily diary study. Journal of Prevention and Health Promotion, 2(1), 135–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/2632077021998261

- Shallcross, A. J., Troy, A. S., Boland, M., & Mauss, I. B. (2010). Let it be: Accepting negative emotional experiences predicts decreased negative affect and depressive symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(9), 921–929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.05.025

- Stockton, D., Kellett, S., Berrios, R., Sirois, F., Wilkinson, N., & Miles, G. (2019). Identifying the underlying mechanisms of change during Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT): A systematic review of contemporary mediation studies. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 47(3), 332–362. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465818000553

September 2022

Utah State University Extension

Peer-reviewed fact sheet

Download PDF

Authors

Jacob Gossner, Beth Fauth, and Tasha Howard