Important Pests of Ornamental Aspen

January 2012

Fred A. Baker, Forest Pathologist • Diane G. Alston, Entomologist (No longer at USU) • Claudia Nischwitz, Plant Pathologist

Detailed Information/Download PDF

Aspens are one of the more popular forest trees in the Intermountain West. They add a brilliant yellow glow to the collage of fall colors. In an attempt to enjoy these beautiful trees around the home environment, many well-intentioned homeowners purchase or otherwise acquire aspens and transplant them into their landscapes. Unfortunately, aspens are not adapted to the environmental conditions of the valleys, and many problems develop.

Aspens are members of the willow family and in the genus Populus. The aspen in the Intermountain West is the quaking aspen, given its name because its leaves quake or tremble in the slightest breeze. This tree grows best in the Rocky Mountains above 7,000 feet elevation, where temperature and moisture conditions are favorable for aspen. Aspens are usually found in groups of genetically identical individuals, called clones. Clones form because aspens reproduce by suckering (sprouting) from roots. As the stems age, they decline and eventually die, and they are replaced by suckers from their root systems. Aspens are short lived; even under optimal conditions, aspen trees rarely live longer than 100 years.

When aspens are planted outside their preferred range, especially so in a landscape situation, they are subjected to many stresses to which they are not adapted. In valleys of the Great Basin, soils are usually alkaline and contain low levels of organic matter, temperatures can be hot in the summer months, and there is often low soil moisture compared to aspen’s native habitats. These stresses reduce tree size and increase tree susceptibility to nutrient deficiencies, insects, and diseases. The ultimate effect of these stresses is to reduce the normal lifespan of aspens in most ornamental situations to less than 25 years. Homeowners must be prepared to replace aspens when their useful life has ended. While some measures can extend tree life, the time gained is often not worth the cost involved.

Many of the pest and nutrient problems that are discussed below occur soon after an aspen tree is planted. When selecting trees or clumps of aspens to plant, choose from healthy clones. The most important consideration is the size of the root mass and the amount of small roots present. The size of the trunk or canopy is unimportant; in fact, the smaller the canopy the more likely the tree will survive. A large, relatively intact root system will soon produce many vigorous, desirable shoots which may outgrow those present when the tree was transplanted. It is best to anticipate transplanting one year ahead, and root-prune or cut the roots around the selected trees in the year before digging for transplantation. This practice greatly increases the success of tree transplantation.

The most common pests and problems of aspens in ornamental situations in the Intermountain West are discussed below, along with suitable measures for their control. These problems may also occur in natural stands of aspen.

Nutrient Problems

Iron Chlorosis or Deficiency

Iron chlorosis of aspen leaves. Image courtesy of William M. Ciesla, Forest Health Management International, Bugwood.org.

Iron chlorosis or iron deficiency is perhaps the most common problem affecting ornamental aspens. Leaves turn pale yellow between the veins, and become more pale during the summer. These symptoms appear about mid-June, or when the weather becomes hot. In some cases, small dead spots may form on the leaves between the veins, but seldom across the veins. Eventually, leaves on the ends of the branches, and sometimes the branches die. Dead branches should be pruned from the tree.

Iron chlorosis or deficiency may be caused by having too little iron in the soil, or iron which is not available to the plant because of alkaline soil or because of excessive or insufficient watering. A quick fix is to apply iron to the leaves. This must be done repeatedly during the season to obtain a green appearance, and treatments must be applied each year because iron is shed with the leaves in the autumn. An alternative approach, more beneficial to the tree over the long term, is to apply a chelated form of iron to the soil around the roots of the tree. Iron chelates are not bound in the soil and slowly release iron to the plant. Applications should be made early in the spring for best results. Not all chelated iron compounds are effective in high pH soils. Products chelated with EDDHA (e.g., Sequestrine 138 or Miller’s Ferriplus) are more effective and work more consistently than other chelates.

A recently recognized cause of iron chlorosis is insufficient watering. Most aspens are planted in lawns and are watered with the lawn. Tree roots compete poorly with grass roots, and are usually deeper in the soil. Most homeowners provide only enough water to saturate the root zone of the turf, causing moisture stress in their trees. This situation will usually become apparent following the first extended hot, dry spell of the year. To minimize stress to the tree, water the trees several times per week, applying at least 1 inch of water to the tree’s root zone each time. The root zone of the tree extends from the trunk to a distance roughly equal to the tree’s height in all directions. During extremely hot periods, or on particularly sandy soils, 2 to 3 inches of water should be applied. Normal lawn sprinklers can be used. To determine how much water is being applied set out several straight-walled cans before sprinkling and measure the amount of water collected.

Insect Problems

Adult Saperda calcarata. Image courtesy of Montana Wildlife Gardener.

Bleeding wound with frass caused by Saperda calcarata.

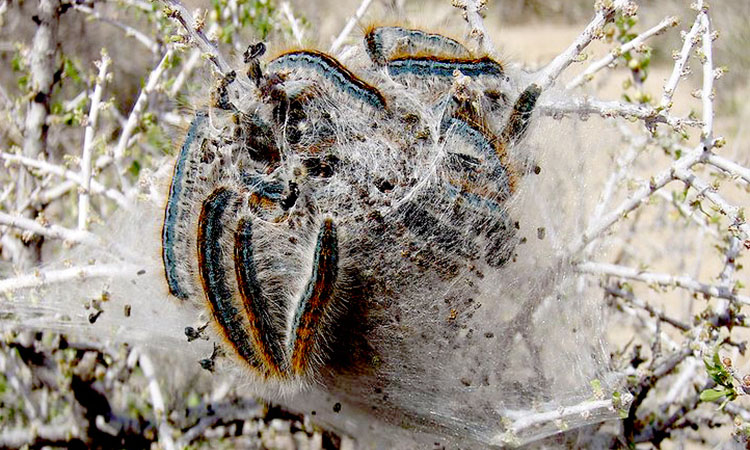

Western tent caterpillars. Image courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

Oystershell scale encrusting a twig.

Aspen leafminer serpentine mines. Image courtesy of Montana Wildlife Gardener.

Aspen galls. Image courtesy of Montana Wildlife Gardener.

Aspen Borer

A number of species of boring beetles attack aspen. The most important is Sapera calcarata, a round-headed or long-horned beetle. The aspen borer locates stressed trees to lay its eggs in cracks and crevices of the bark. In northern Utah, it has been observed that trees of approximately 3 to 5 inches in trunk diameter have been attacked more than both very young and larger trees. The damage is caused by the larvae which tunnel in the trunk of the aspen for perhaps several years. Their tunneling often weakens the wood of the trunk and allows invasion of canker and decay fungi. The tree may ultimately break in a wind or snow storm. Larval activity is evident by accumulations of fibrous, coarse wood fragments called frass. Affected trees often “bleed” sap from borer wounds.

The most effective deterrent to borers is to maintain trees in a vigorous condition. Systemic insecticides, those that are translocated within the tree, can provide suppression of round-headed borers, but may not completely eliminate them. Imidacloprid (Bayer Advanced Garden, Merit, and many other brands) and dinotefuran (Safari) are systemic insecticides that can be applied to the root-zone (dripline) or injected into the trunk. Preventive trunk sprays can be effective if used consistently. Protecting trunks from egg-laying adults during May and June is the primary timing for northern Utah (3 to 4 weeks earlier in the south). Carbaryl (Sevin), permethrin (many brands), or bifenthrin (many brands) are recommended, but sprays must be reapplied according to the product label’s protection interval throughout the approximately 2 month period of adult activity to prevent infestation. One of the most effective approaches to dealing with borers in aspens is to remove the infested trunk, and select one or several suckers as replacements.

Tent Caterpillar

The western tent caterpillar commonly defoliates aspen, forming a web “tent” around several leaves to protect themselves from predators. Tent caterpillars rarely cause tree death; they simply are unsightly. Healthy trees will usually re-foliate by summer following tent caterpillar damage. If tents aren’t too numerous and tree canopies are accessible, prune out limbs with tents when they first appear. Tents can also be burned from trees. Make a torch by wrapping a kerosene-soaked cloth rag around the end of a pole and igniting it. Carefully burn out the tents and caterpillars in the spring without harming the adjacent limbs. The microbial insecticides, Bt (Dipel, Thuricide, other brands) and spinosad (Conserve, Entrust, Success, other brands) can be highly effective if leaves are thoroughly covered, as the larvae must ingest the microbial insecticide in order to be killed. Acetamiprid (Assail, Ortho Max, others) has translaminar (local systemic) uptake when applied to leaves. The systemics, chlorantraniliprole (Acelepryn), dinotefuran (Safari), and imidacloprid (Bayer Advanced Garden, Merit, others) can be applied to the roots or injected into trunks of larger trees that are difficult to cover with a canopy spray.

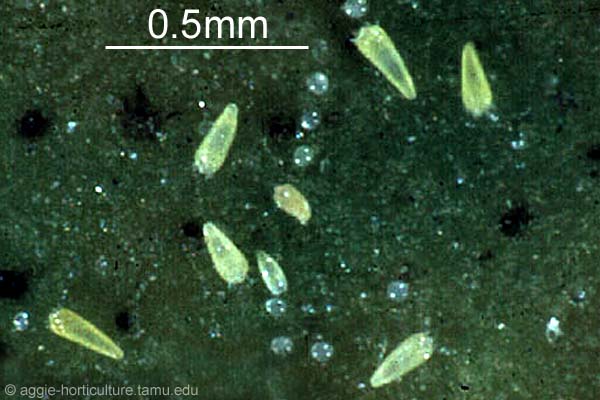

Oystershell Scale

Oystershell scale forms crusts on twigs and limbs. These insects suck sap and often kill branches and in some cases, whole trees. Aspens with scale infestations are unsightly, weakened, and limb dieback is common. Apply dormant oil just before bud break in the spring to suffocate the overwintering scale. Apply the systemic insecticide dinotefuran (Safari) in the spring at the first flush of tree growth. Another option is to monitor the activity of the young nymph stage, called crawlers, with sticky bands placed around infested limbs. When small, yellow crawlers collect on the bands, apply a contact insecticide such as bifenthrin, carbaryl, permethrin, or malathion.

Aspen Leafminer

Leafminer larvae feed on leaves and form blotches or serpentine patterns which are unsightly. Feeding damage may cause the leaves to drop early, but in most cases leafminer infestations are not severe enough to significantly affect tree health. Control of leafminers is not always warranted. If treatment is deemed necessary, treat foliage when leaves are half-sized, approximately in May to June (in northern Utah; 3 to 4 weeks earlier in the south) when mines are first observed. Bifenthrin, carbaryl, permethrin, malathion, or spinosad may provide suppression, but complete elimination is usually difficult because the insect is active over an extended time period.

Aspen Galls

Several insects cause swellings in stems, shoots, leaves, and petioles of aspens, called galls. Most galls cause local injury that does not affect tree growth or survival. Some premature leaf drop can occur. Management is rarely justified, and may not be practical, because insects within galls are not vulnerable to insecticides. Adults emerging from the galls to lay eggs may be suppressed with contact insecticides, such as bifenthrin, carbaryl, permethrin, or malathion; however, multiple applications are required to cover the activity period. Prune out limbs that have heavy galling. Tree health and longevity is usually not affected by aspen galls.

Disease Problems

Leaf diseases on aspens are causes by several different fungi. In ornamental situations, they rarely cause tree mortality. More often, however, they cause unsightly leaves, and affected trees shed their leaves earlier in the growing season, often without producing the desirable fall coloration. Foliar diseases affect the tree’s appearance more than they affect its well-being, although the tree may grow more slowly with repeated annual attacks. Infested leaves drop to the ground and therefore the fungus must re-infect healthy leaves the following spring.

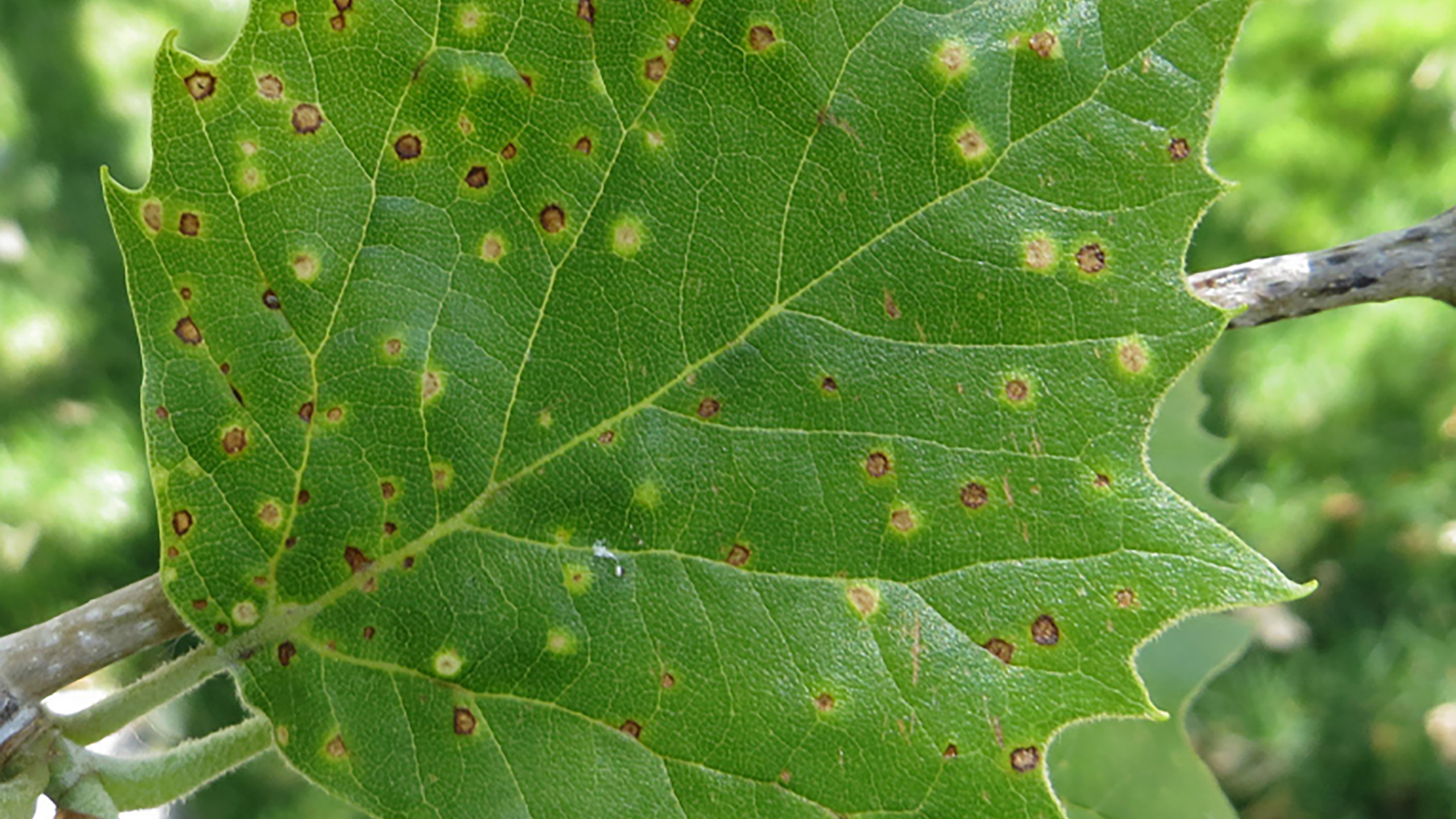

Marssonina leaf spot.

Aspen Leaf Spot

The most common foliar problem on aspen is aspen leaf spot caused by the fungus Marssonina pupuli. This fungus causes dry, brownish lesions with yellowish borders. Margins are often irregular and indistinct, and not restricted by veins as are those caused by iron chlorosis. Infection is favored by wet weather, especially when the aspen leaves are emerging from the buds. During particularly wet springs, extensive infection can occur throughout aspen forests, resulting in massive defoliation and a loss of the delightful fall color. After several years of defoliation the disease may even kill aspens.

In the home landscape, the impact of this leafspot can be minimized by increasing the vigor of trees by proper watering and fertilization. Vigorous trees can produce new leaves, free of disease, that can make the sugars that the tree needs to continue growing. In most cases, increasing vigor is all that is needed to ensure tree survival.

When trees have been defoliated two or more consecutive years, or the trees are key landscape trees, fungicide use may be warranted. Labeled fungicides include chlorothalonil (Daconil 2787, Daconil Lawn and Garden Fungicide, Broad Spectrum Fungicide) or fixed copper fungicides (Microcop, Copro, Kop-R-Spray, Kocide 101, Champ). One of these fungicides must be applied at label rates beginning at budbreak and applications should be made at 10 to 14 day intervals as long as wet weather continues or until leaves reach their full size. Sprinkler irrigation on foliage should be avoided because it creates conditions favorable for infection and can spread spores.

Destroying fallen leaves is often recommended for controlling this and other leaf diseases. However, this practice may be of limited value because spores of leaf disease fungi can often travel great distances from untreated aspens and thousands of spores can be produced on leaves that remain. In dry years, removing the nearby source of spores is of little benefit because conditions do not favor infection; in wet years, a single spore source can provide enough spores to infect many trees. Therefore, nothing more intensive than the normal fall leaf raking is necessary.

Ink spot. Image courtesy of William Jacobi, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org.

Powdery mildew.

Leaf scorch. Image courtesy of William M. Ciesla, Forest Health Management International, Bugwood.org.

Cytospora canker. Image courtesy of William Jacobi, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org.

Ink Spot

Ink spot is a leafspot restricted to high elevation aspen stands. This leafspot is easily distinguished from other foliar problems by the presence of large, flat, black fungal structures on the leaves. These spots resemble drops of ink or tar. Later in the summer, the black structures may fall from the leaves, leaving roundish holes in the leaf. This disease is not a problem of ornamental aspens in lower valleys, but is often mis-named by homeowners when they see aspen leaf spot. Control is not warranted for ink spot.

Powdery Mildew

Powdery mildew produces a grayish coating over the leaf. This powdery mass consists of the thread-like mycelia and spores of the fungus. Powdery mildews are unusual in that unlike most fungi they grow well under dry conditions. Although it detracts from the appearance of leaves, powdery mildew causes little damage to aspens, and control is usually not justified.

Leaf Scorch

Leaf scorch is a foliar problem caused by insufficient soil moisture. In aspens, leaf scorch is usually limited to ornamental situations. Leaf margins are killed when the tree cannot supply enough moisture to the leaves during hot, dry weather, especially when it is windy. Leaf scorch is aggravated by iron deficiency. Proper watering - enough to saturate the tree’s root zone - can prevent further damage.

Cytospora Canker

Cytospora canker is one of the most common diseases affecting aspen twigs and stems in ornamental situations. This fungus invades wounds—those caused by humans as well as those made by insects, branch rubbing, and other “natural” causes. This fungus is a parasite of weak and dying trees in natural stands, and often attacks stressed trees in the landscape. Once Cytospora invades a wound, it often girdles a branch by killing the cambium. Vigorous trees, however, can limit the invasion and are rarely killed. Therefore the most effective control is to encourage tree vigor by providing adequate water and fertilizer. Pruning of the affected branch is recommended to prevent the infection from progressing into major branches, but its value is mainly to remove dead branches and improve the tree’s appearance. Fungicides are not effective.

Trunk and Root Rot

Several fungi may decay the roots and trunks of aspens, especially those of larger or older trees, causing the trees to break. These fungi are usually not a problem in ornamental aspens when they fall. If these fungi are present and the trees could damage some property if they fall, the trees should be removed.

Pesticide Precautions

Always read the product label for registered uses, application and safety information, and protection intervals. All brands are registered trademarks. Examples of brands may not be all-inclusive, but are meant to provide examples of products registered in Utah. The availability of pesticides may change.